The Steamship William G. Mather, the 100-year-old ore carrier moored at dock 32 at Cleveland’s North Coast Harbor, is a stirring embodiment of the city’s industrial age.

But the “ship that built Cleveland,’’ as it’s called, is also a giant view blocker. Its black hull is a wall of steel roughly two stories high and 618 feet long.

Depending on where you stand nearby, the Mather blocks sunrises and sunsets, and views of Voinovich Park and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, across the water on the east side of Cleveland’s North Coast Harbor.

For those reasons, it’s good news that the Great Lakes Science Center, which has owned and operated the Mather for two decades as a floating museum next door at the harbor, is open to relocating the ship as part of a massive revamp of the downtown lakefront, scheduled to start construction in 2027.

“The Great Lakes Science Center is an enthusiastic participant in the conversation about making the lakefront a terrific public asset,’’ Kirsten Ellenbogen, the center’s director, said in a recent interview. “If that involves the Mather being in a different location, that's a conversation we're willing to have.’’

Moving the ship, which attracts more than 14,000 visitors per year and will reopen for tours in the spring, won’t happen any time soon. But Ellenbogen said the ship could be combined in the future with the U.S.S. Cod, the World War II submarine, as part of a potential new maritime museum in a yet-to-be-determined waterfront location.

Over the long haul, that museum could also include the U.S.S. Cleveland, a Navy combat ship scheduled for commissioning in Cleveland this spring, Ellenbogen said. A private foundation is already planning for the ship’s future after it completes its service.

Why views matter

The idea of moving the Mather highlights a key issue for the next stage of lakefront planning and design starting this winter: that of creating, enhancing and preserving views of Lake Erie, waterfront attractions and the Downtown Cleveland skyline.

Architects and city planners have known for millennia that humans are hard-wired to seek views because they’re essential for mental mapping and wayfinding. Views, whether broad panoramas or streetscapes that focus the eye on the horizon or a distant landmark, have emotional and economic power.

Getting it done

Cleveland hasn’t always followed these principles on the lakefront. After creating North Coast Harbor in the 1980s, it virtually walled in the seven-acre basin with the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the Great Lakes Science Center and the city’s football stadium. The harbor also feels cut off from downtown by the Ohio 2 Shoreway and lakefront rail lines.

Numerous earlier attempts to expand the waterfront with new connections and development failed for lack of follow-through and civic will. But now the city has a once-in-a-century chance to get it right. The latest effort, about four years in the making, has money, momentum, political support and administrative structures in place to make things happen.

Jimmy and Dee Haslam, the owners of the NFL Browns, kickstarted the process in 2021 by paying for a $1 million proposal for new lakefront development and connections.

Their concept included building a “land bridge’’ to extend the downtown Mall — the 15-acre green space in the heart of Cleveland’s government and civic center — north across the Shoreway and lakefront rail lines.

The Haslam plan, led by New York-based landscape architect Thomas Woltz, identified numerous sites for new hotels, apartments and offices in positions designed to frame views of the lake, not block them.

The land bridge was intended to channel thousands of fans easily from the Mall to the lakefront stadium. That idea became moot when the Haslams withdrew from the lakefront project, opting to build a new covered stadium in suburban Brook Park as soon as 2029.

The city is forging ahead now without the Haslams and the Browns. Mayor Justin Bibb sees the lakefront as a critical piece of his “shore-to-core-to-shore’’ vision of making Cleveland a true, two-waterfront city.

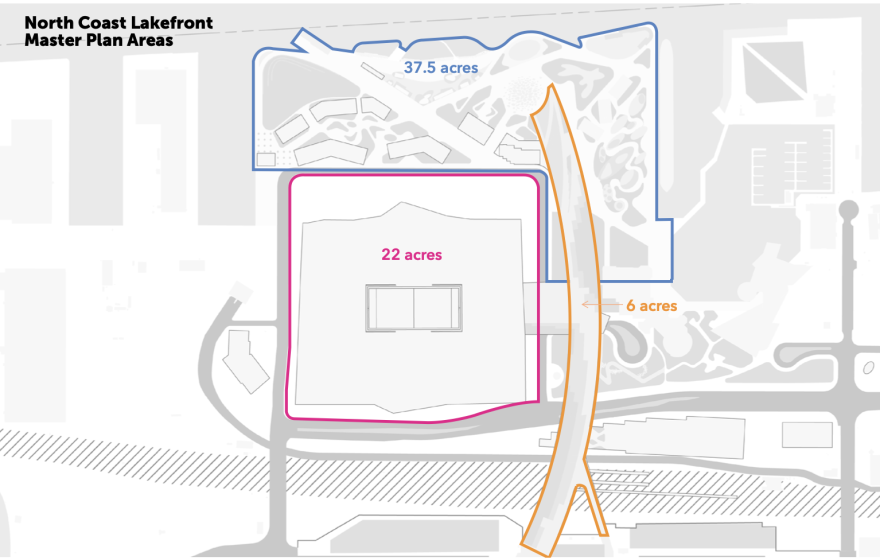

The land bridge, now called the lakefront connector, is still the centerpiece of the city’s plan, but the stadium, which occupies 22 acres, will be demolished when the Browns leave, giving the city roughly 50 acres to redevelop.

To boot, the Federal Railroad Administration has devoted nearly $1 million to planning a new lakefront multi-modal transit hub just south of the Shoreway as part of the project.

Ready to go

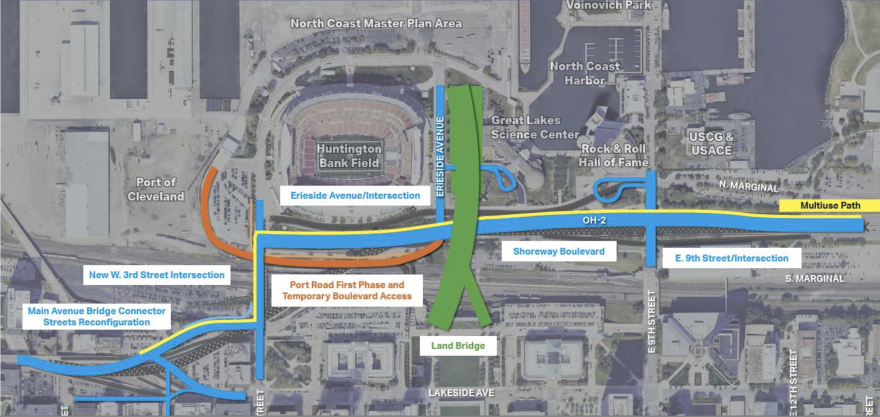

Cleveland is ready for the moment. Over the past year, it amassed $20 million from the State of Ohio and another $130 million from the federal government. The money will help pay for the lakefront connector and redoing the Shoreway as a slimmer, 35 mph boulevard instead of a wide, high-speed freeway. The federal money has not been clawed back by the Trump Administration as in other blue cities.

The total needed by the city for lakefront infrastructure in the current stage of work is $284 million. The $134 million needed above the state and federal grants could be leveraged by the new downtown tax increment financing district the city created last year. The Haslams will also devote $100 million toward demolishing the lakefront stadium and other related expenses.

The planning so far

In 2023 and 2024, the city held extensive public meetings to refine its lakefront vision in a process led by Field Operations, the landscape firm that co-designed New York’s popular High Line Park. The city also established the nonprofit North Coast Waterfront Development Corp. to carry out lakefront projects continuously across election cycles, plus a New Community Authority empowered to raise capital from sources, including the sale of bonds backed by the new downtown TIF district.

The development corporation will soon identify a master developer for the 50-plus acres on the lakefront and will pick a landscape design firm to update and expand on the earlier work by Field Operations, including on the acres now occupied by the Browns stadium.

“We need to start to look at the site with fresh eyes,’’ said Scott Skinner, the head of the development corporation.

The city, meanwhile, will in 2026 identify a design-build team to complete designs and start construction on the Shoreway and the lakefront connector by 2027, the deadline to start drawing down the federal money. At this point, plans for the Shoreway and connector are about 20% complete, city officials said.

Skinner said his nonprofit and the city will coordinate all their work. Updated lakefront plans could be ready for public review and feedback as soon as next summer.

Unresolved design issues

Given the progress since 2021, it may seem that all the big design questions have been resolved on the lakefront. That’s not the case.

The original plan led by Field Operations identified sites for offices and housing that would have hugged the north side of the stadium, overlooking proposed new park spaces, a wading beach and a promenade.

But with the stadium now headed for demolition, the building sites in the earlier plan make no sense. They’d block views of the lake from the 22 acres that will open up when the stadium comes down. The next round of planning should try to pull views of the water as deep into the property as possible, not wall them off.

As for the lakefront connector, early renderings suggest its upper surface will be a beautiful, elevated linear park with great views of the lakefront and the skyline.

But what will the structure look like when seen from the Shoreway, or adjacent sidewalks below? Will it have graceful steel arches, or heavy-looking concrete columns and beams? Can it be lighted at night as a thing of beauty?

Ellenbogen knows what she doesn’t want: She said that walking under the connector, near the science center, shouldn’t be “a tunnel sort of experience.’’

North of the Shoreway and Erieside Avenue, the connector will shelter a 900-space garage that will replace the existing 600-space facility attached to the science center. If the new garage carves up the landscape and blocks views, it could be a net negative. Where it intersects the science center will be a very tricky problem to resolve.

On the Shoreway, engineers are still studying how the intersection at East Ninth Street, just south of the Rock Hall, could be reconfigured to be more pedestrian- and bike-friendly than it is today.

Another huge question is whether the Shoreway will end at West Third Street, requiring westbound motorists to jog south to Summit Avenue or Lakeside Avenue in order to access the Main Avenue Bridge over the Cuyahoga River. A similar shift would also be required eastbound.

The “jog’’ would enable the city to tear down the elevated ramp that now connects the Shoreway to the Main Avenue Bridge. The ramp is an eyesore that constitutes a visual and physical barrier between downtown and the lakefront. Removing it would be good for connectivity and views.

But Ward 17 Councilman Charles Slife doubts the wisdom of removing the ramp. At a recent meeting of the city’s planning commission, he worried that the “jog’’ could cause delays for east-west commuters driving across the lakefront.

If the Main Avenue Bridge ramp remains, however, it will hurt the city’s goal of improving connections from downtown to Lake Erie. It’s a question of what’s more important: mobility or place.

Precedent to follow

If the city and the North Coast Waterfront Development Corp. want precedents to follow as they refine the lakefront plan, they have great local examples.

One is the Solstice Steps at Lakewood Park in Lakewood, a series of terraces designed to capture midsummer sunsets over Lake Erie.

In Cleveland, the new park taking shape at Irishtown Bend in Ohio City could soon become one the most compelling new waterfront parks in America, based on views of the downtown skyline and the Cuyahoga River, and its connection to regional trails.

Another example to follow is that of the Gateway sports complex, where Progressive Field and Rocket Arena are located. Built 31 years ago on the south side of downtown a mile south of Lake Erie, Gateway located its main buildings brilliantly to frame skyline views and ground-level pathways with clear lines of sight that make them easy to navigate.

Gateway shows that Cleveland’s city builders, at their best, know how to shape urban vistas that create value, connectivity and a strong sense of place. Planning for the downtown lakefront hasn’t reached that level of quality yet. Moving the Mather could be one step among many still needed to get there.