Akron has always asserted its own identity and has never wanted to be subsumed into Greater Cleveland. So how does the city define itself in a positive sense, apart from not wanting to be gobbled by its neighbor to the north?

Exhibitions on view through the holidays at the Akron Art Museum provide some answers, at least from an artistic point of view. Given that some of the displays were meant to coincide with the city’s 2025 bicentennial, it’s worth seeing how they and other exhibits define the city’s sense of itself and, perhaps, its soul.

What they say, as a whole, is that Akron is a place with unexpected natural beauty, a gritty spirit of creative freedom and a sense of community pride and solidarity that comes from being overlooked and underestimated.

Local art hero

All of those qualities can be seen in the museum’s main bicentennial exhibition, a large-scale retrospective on the work of Akron native Alfred McMoore (1950-2009), an eccentric “outsider,’’ or self-trained artist, diagnosed as a schizophrenic in his teens.

McMoore lived in psychiatric institutions from age 18 to 39. For the following 20 years, he shared an apartment with a roommate while receiving aid from the nonprofit Community Support Services, which coordinated meals, medical care and visits from a social worker.

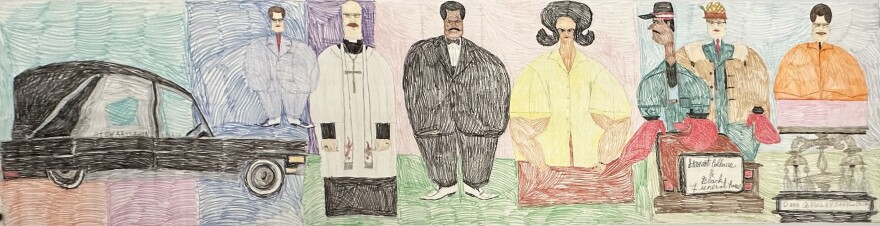

McMoore started making massive pencil drawings on five-foot-wide rolls of paper in his teens. Many showed his enduring fascination with funerals, funeral homes and rituals of death and dying. He is said to have attended thousands of funerals.

McMoore attracted a coterie of friends and supporters who provided him with art supplies, admiration and everyday contact. His inner circle included the late art and antiques dealer Chuck Auerbach, who died in Nashville in March, six months before the exhibition opened, and Akron Beacon Journal reporter Jim Carney. Their respective sons, musicians Dan Auerbach and Patrick Carney, co-founded the Grammy winning blues-rock band, The Black Keys, in 2001. They named it after McMoore’s frequent use of the phrase “black keys’’ as a cryptic way to express impatience or displeasure, as in, “your black key is missing,’’ or “don’t be a black key.”

In a documentary screened in the exhibition, Chuck Auerbach described the Black Keys in a way that could apply to the larger creative spirit of Akron.

He said that the city is “a wonderful place for an artist to grow up. First of all, there's no expectations of success coming from Akron, Ohio. Second of all, because there's no expectations of success, there's no pressure to be anything or produce anything in a certain way. In Akron, where there is not much of a scene; you kind of create your own scene.’’

That description fits McMoore, whose drawings emanate a manic, urgent intensity. His epic portrayals of funeral processions and burials unfurl across wide expanses of white paper like the sculptural friezes that wrapped ancient Greek temples or coiled around triumphal columns in ancient Rome, albeit with entirely different intentions.

The drawings are populated by priests, mourners, sheriff’s deputies and the departed, lying face-up in their caskets. He often used made-up names on officer’s nametags or depicted funerals for people who were still living. Oddly, he often covered his mourner’s hands with boxing gloves. He also played with gender by portraying male officers with dangling earrings and high heels.

“Sexual identity confusion is certainly a common symptom of schizophrenia,’’ museum Curator Wendy Earle said in an interview, adding that McMoore may have feminized his deputies “as a way to take away their power.’’

McMoore’s drawings have a crackling linear energy and passion for details that can be appreciated fully only in person; they don’t reproduce well in photographs. Seeing them up close shows how McMoore drew everything in his images as if he were touching every physical object with his hands. Badges, weapons and creases on police uniforms have a crisp, tactile clarity. The same is true of the crystalline facets of cut-glass lamps and chandeliers in funeral homes, and the swooping contours of hearses.

On view through Feb. 8, the show makes the point that people with mental illness can lead full, creative lives. It frames Akron as a place where people such as McMoore can find fulfilment and community. The total package has a true genius loci, or sense of place.

The McMoore show also embodies the Akron museum’s interest in collecting works by outsider, self-trained or folk artists, a focus encouraged by the late Mitchell Kahan, who directed the institution from 1986 to 2013.

A glimpse of Haiti

Another solo show, on view through Jan. 4, doubles down on the folk-art focus by exhibiting 10 flag-like tapestries by Haitian artist Myrlande Constant. Born in Port-au- Prince in 1968, Constant attained mastery in the early 2000s in drapo (meaning flag in Haitian French), the traditionally male, priestly art of encrusting large sheets of fabric with sequins to make images that portray intricacies of the Vodou religion. Constant has expanded the tradition by adding beads to her drapo practice.

Filled with lush colors, glittery surfaces and vibrant patterns and shapes, Constant’s crowded scenes combine landscapes and portrait figures both real and mythological. Her work gained wide attention after having been shown at the Biennale in Venice in 2022, a major international exhibition.

The Akron show centers on “Sosyete Radha,’’ recently purchased by the museum. It’s the largest drapo in the show, combining scenes of rural prosperity with images honoring the primordial creators of life on earth in Vodou mythology.

Constant, who works with a small army of assistants who have started their own artistic practices, has said she views her work as an expression of hope for an end to gang violence and a return to peace and stability in Haiti.

By showing — and buying — Constant’s work, the Akron museum is joining other American art museums in giving overdue attention to Afro-Caribbean art. The exhibition has an up-to-the-minute freshness and urgency.

Beauty in poisoned land

The third major show at the museum, on view through Jan. 25, focuses on historic landscape photographs by Robert Glenn Ketchum from his late 1980s portfolio, “Overlooked in America,’’ which helped draw attention to mismanagement of federally-owned lands across the U.S.

Ketchum used the Cuyahoga Valley National Recreational Area, created in 1974, as a specific example of a national problem. He contrasted images of natural scenery between Akron and Cleveland with written descriptions of pollution that marred beauty spots such as Brandywine Falls.

His project, published by Aperture in 1991, created pressure for cleanup efforts and helped convince lawmakers to upgrade the CVNRA to full national park status in 2000.

Today, the Ketchum photos can be seen as part of the history of America’s environmental movement and as a visual hymn to the natural wonders that lie between Cleveland and Akron.

Moment of strength

All three special exhibitions at the museum show how it has recovered from a rough patch during the 2020 pandemic, when accusations of workplace violations led to community protests and a turnover in leadership.

Since then, the museum has stabilized under Director and CEO Jon Fiume and has continued to articulate its perspective on modern and contemporary art.

The museum also continues to capitalize on the dramatic architecture of its main building, completed in 2007 as an expansion of its original home in Akron’s 1899 post office at East Market and South High streets, a structure now undergoing a renovation.

The 2007 expansion, designed by the Viennese architecture firm of Coop Himmelb(l)au, combines the jagged, explosive shapes of a glass-enclosed lobby with a winglike roof overhead that unites the post office and lobby with a collection of boxy new galleries that appear to float above South High Street.

Nicolai Ourousoff, then the architecture critic of The New York Times, viewed the project with skepticism in his 2007 review. He praised the building’s intentions as an energetic response to a “lifeless Midwestern strip,’’ but sneered at what he called the museum’s “uneven 20th-century collection’’ and the lack of skylights in the “lifeless sequence of interchangeable rooms’’ on the main exhibit level.

Sparkling collection, loans

Since then, the museum has created a string of installations for its permanent collection and special exhibitions that have added definition and spark to the main galleries. That’s especially true now. In addition to the three main shows mentioned above, the museum features a sequence of thematically organized displays that highlight works from the permanent collection, plus works on loan from other museums.

Highlights include a room-size installation created in 2013-2023 by American artist Petah Coyne in which taxidermized white and silver peacocks perch in the branches of two conserved apple trees. Wintry, elegant and otherworldly, the installation is a fairytale landscape made real.

The installation is on loan from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia, with support from the Art Bridges Partner Loan Network, a project of philanthropist Alice Walton, the daughter of Walmart founder Sam Walton and founder of the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Ark.

Also, on loan from Art Bridges is “Portrait of Qusuquzah #5,’’ 2011, an outstanding, glittery portrait of a Black woman by American artist Mickalene Thomas. It anchors a room devoted to images of Blacks in American life.

Individual works sprinkled throughout the permanent collection galleries to celebrate Akron’s bicentennial include Raphael Gleitsman’s “Winter Evening,’’ 1932, a classic nocturnal view of the Rubber City during the Depression.

With its snow-filled streets and shop windows aglow beneath a skyline of looming office towers, it’s a vivid example of American Scene regionalism on par with examples by more famous artists such as Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry. Just as their works captured the look of Depression-era Iowa, Missouri and Kansas, respectively, the Gleitsman feels completely rooted in Akron, just like the museum that owns it.