Updated August 1, 2022 at 12:38 PM ET

African Americans throughout the nation celebrate Juneteenth, but who knows what actually happened on June 19, 1865? As the nation observes the second federal legal holiday marking the emancipation of enslaved people in Texas, there are a number of misconceptions about the historical event that keep getting repeated.

Myth #1: President Abraham Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863, and it's outrageous that it took two and a half years for the news to finally reach enslaved people in Texas.

Fact: Many slaves knew about Lincoln's executive order emancipating them. The news was widely covered in Texas newspapers—with an anti-abolitionist spin—and Black people would have overheard white people discussing it in private and in public. Moreover, "There was an incredibly sophisticated communication network among slaves in Texas," says Edward T. Cotham, Jr., Texas Civil War historian and author of Juneteenth, The Story Behind The Celebration. "News like that spread like wildfire. We know some slaves knew about the Emancipation Proclamation even before slaveowners. It didn't mean anything because there was no army to enforce it."

June Collins Pulliam is a fifth-generation Galvestonian whose enslaved great-great-grandparents, Horace and Emily Scull, were freed by the Juneteenth Order. "It wasn't that all these poor people didn't get the message," she says, "It was that there was no one enforcing it, no one making it happen!"

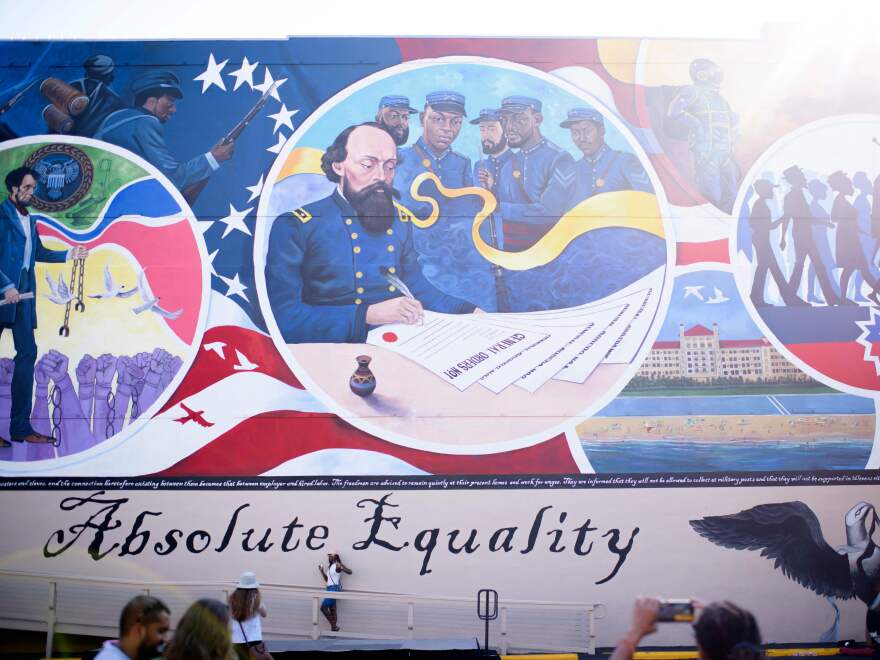

Myth #2: Major Gen. Gordon Granger penned General Orders No. 3, the Juneteenth Order, and is credited with freeing Texas slaves.

Fact: The order—which includes the powerful language "all slaves are free" and "absolute equality"—was actually written by Granger's staff officer, Maj. Frederick Emery, who hailed from an abolitionist family in Free Kansas. "As a crusader against slavery in Kansas, Emery was well versed on the subject of emancipation," writes Cotham in his Juneteenth book.

Sam Collins III, the unofficial ambassador of Juneteenth tourism in Galveston, says, "Granger is just one of the characters in the story. He's not any great hero. Matter of fact, he was no friend of the enslaved people. There are reports of Granger sending runaway slaves back to slave states."

Editor's note: After NPR posted this story, the descendants of Gen. Granger contacted us to offer a rebuttal. The family included a blogpost by Granger's biographer, Robert C. Conner, which includes the following: In reality, Granger was a major general commanding all federal troops in Texas. As a major on his staff, Emery was a much junior officer essentially acting as Granger's secretary. He may have written out the order and advised on its wording, but Granger would have paid very close attention to the language, including the reference to freedom meaning "an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves."

Myth #3: Gen. Gordon Granger read the Juneteenth Order from a balcony to the people of Galveston, announcing that "all slaves are free."

Fact: According to Cotham, Gen. Granger never read the order publicly, nor did any member of his staff. It would have been posted around town, particularly at places where Black people gathered, such as "the Negro Church on Broadway," as Reedy Chapel-AME Church was then called. Most enslaved people in Texas learned of General Orders No. 3 when the slavemaster called them together and read them the news.

Myth #4: The Juneteenth Order was basically a Texas version of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Fact: General Orders No. 3 stated unequivocally "all slaves are free," but it also contained patronizing language intended to appease planters who didn't want to lose their workforce. Forty-one words of the brief 93-word order urged enslaved people to stay put and keep working.

"The freed are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere."

Sam Collins: "The last two sentences advised the freedmen to remain at their present homes and work for wages. So you're free, but don't go anywhere."

Ed Cotham: "Many years later, the formerly enslaved (interviewed for the 1930s WPA Slave Narratives) remembered when the Freedom Paper was read to them. The slaveholder wanted to keep them working, but they didn't hear it that way. Once they heard "all slaves are free" they said to hell with you. That's what made the Juneteenth Order so memorable and made it succeed."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.