No one likes it when a new drug in people's medicine cabinets turns out to have problems — just remember the Vioxx debacle a decade ago, when the painkiller was removed from the market over concerns that it increased the risk of heart attack and stroke.

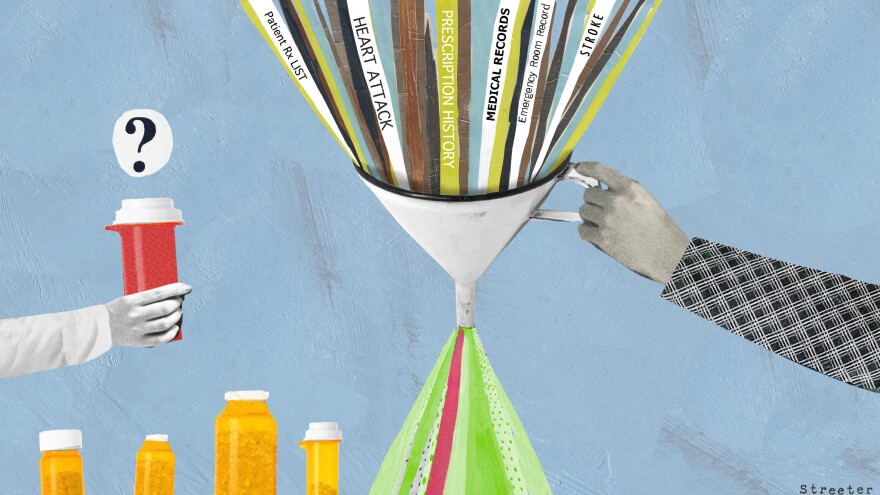

To do a better job of spotting unforeseen risks and side effects, the Food and Drug Administration is trying something new — and there's a decent chance that it involves your medical records.

It's called Mini-Sentinel, and it's a $116 million government project to actively go out and look for adverse events linked to marketed drugs. This pilot program is able to mine huge databases of medical records for signs that drugs may be linked to problems.

The usual system for monitoring the safety of marketed drugs has real shortcomings. It largely relies on voluntary reports from doctors, pharmacists, and just plain folks who took a drug and got a bad outcome.

"We get about a million reports a year that way," says Janet Woodcock, the director of the FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. "But those are random. They are whatever people choose to send us."

Figuring out from those reports if a drug is really to blame for the symptom isn't easy. And if the side effect is something common, such as a rash or a stroke, there might not even be any reports because doctors might not connect a patient's symptoms to the drug.

"We need a rapid way to find out what's happening with drugs, especially safety of drugs, after they're approved and on the market," says Woodcock.

That's why the FDA is turning to workers at the operations center of Mini-Sentinel, which is located in a brick office building near Fenway Park in Boston.

Here, people in cubicles can send out queries to 18 data partners that include health plans and insurance companies. Their health records include nearly 180 million Americans.

If you have insurance through a private health plan, the chances are "pretty good" that your data may have been used in one of these studies, says Dr. Richard Platt, the principal investigator for Mini-Sentinel and a professor at Harvard Medical School's Department of Population Medicine.

Almost all of that data comes from billing records — not what your doctor has scribbled in your chart, but rather the codes for any diagnostic tests and procedures you undergo. (These codes are on your medical bill.) Platt says the data partnership has been carefully set up to preserve patient privacy.

His own records have probably been part of a study, says Platt, but he has no way of knowing that. "We've built the system so the analyst here would have no way to say, 'Let's see if Dr. Platt's data is in there,' " he says. "The system is built so that that is an impossible question to ask."

It's taken five years for Platt's team to build Mini-Sentinel from scratch and make it a routine part of FDA's work. "We're now doing hundreds of queries a year," he says.

For example, they ran a search when the FDA got some troubling reports tentatively linking intestinal problems to a blood pressure drug called olmesartan.

"They had noticed that patients who had received this drug were having these complications that they thought might be related to the drug," recalls Platt.

At first, Mini-Sentinel found no connection. Then the FDA asked for a second search, this time focusing on people who took the drug for long periods. They found a link, Platt says. As a result, the FDA added a warning to the drug's label.

"It was possible to provide an answer that otherwise would frankly just be unavailable to them," says Platt.

Mini-Sentinel has been an experiment to see what's possible, but its contract ends in September and the FDA will be deciding what to do next.

Almost everyone agrees that the ability to sift through huge amounts of patient data is the way of the future — but not everyone believes that we really know how to best do that sifting yet.

"I think it's a good and important step that the FDA is moving in this direction," says Thomas Moore, a senior scientist at the nonprofit Institute for Safe Medication Practices. "The problem is, I think, they have underestimated how far they have to go."

Billing data were never meant to be used this way, says Moore, who questions how well they can reveal side effects from drugs. He thinks "the biggest danger is that people will get a false reassurance about safety."

He points to a controversy over a new blood-thinning medicine called dabigatran. Reports had come in about serious bleeding episodes, says Moore, but "the FDA published an article in a leading medical journal, basically discounting all that — saying that, using Mini-Sentinel, they had seen no unusual risk for this drug."

The agency is now taking another, more nuanced look at dabigatran, after critics questioned how well the FDA had designed the original Mini-Sentinel study.

People at the FDA are aware that when doing this type of research with big data, the way you set up the question can affect the answer.

"Things may change depending on what claims data set you use, or how you run your definitions, how you set up your parameters and so forth," says Woodcock. "And there's no doubt these studies are vulnerable to all these changes."

She says that's why the FDA is also involved in another effort to explore all these potential effects. This effort is led by The Reagan-Udall Foundation for the FDA, a foundation set up by Congress. Right now its major project is research on how to use large databases to study the safety of medicines on the market.

"This is a new science, and much work needs to be done to develop and continue to improve the methods behind this," says Troy McCall, who is managing the project for the Reagan-Udall Foundation.

The foundation does get some money from the FDA, but supports its research with other funds. And so far, all the money for this particular project has come from pharmaceutical companies like Merck, Pfizer, Novartis, Johnson & Johnson, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca and Eli Lilly.

McCall says he doesn't think it's seen as an "'industry project," because the work is so important. "Clearly at the end of the day this is all to benefit patients and ensure that drugs that are on the market are safe," he says, adding that patients also benefit when safe drugs are not unnecessarily removed from the market.

Drug companies do have a big interest in what stays on or off the market. But Woodcock sees no problem with industry funding the development of the scientific methods that will then be used to help make regulatory decisions.

"It would be very difficult to develop a method that was going to favor your drug when you're developing a general method, I think," Woodcock says. "But what I would say is, OK, who is going to develop these methods? We need them developed."

Officials at the Reagan-Udall Foundation say it operates transparently and has different stakeholders represented on its governing boards. But one board member who represents consumers says she finds the lack of independent funding troubling.

"I think that creates an appearance of a conflict of interest and potentially a real conflict of interest," says Diana Zuckerman, president of the nonprofit National Center for Health Research. "If all the money is coming from the pharmaceutical companies whose livelihoods are going to be affected by what the project finds, I just think that's an untenable situation."

Zuckerman says she worries that industry funding might influence the methods that eventually get used for finding signals in big data that drugs are unsafe — and that could potentially limit what this new approach will reveal about the medicines Americans take every day.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.