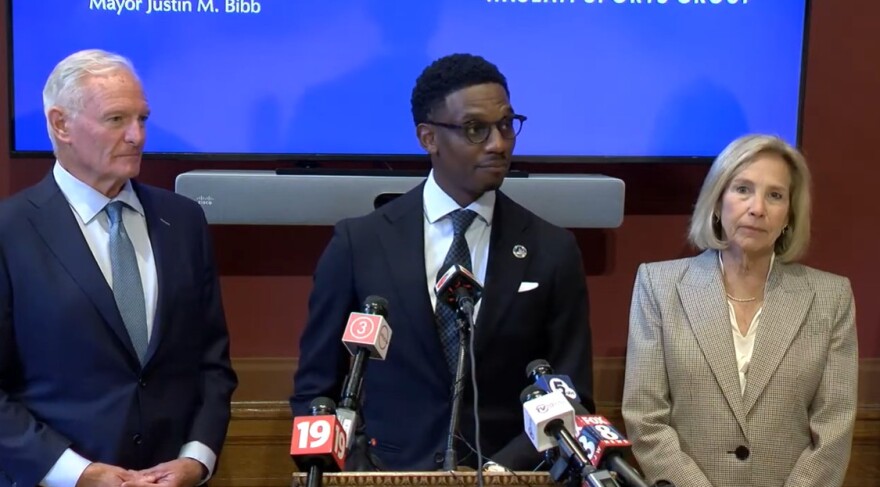

Mayor Justin Bibb's $100 million exit settlement with the Browns' owners is now official after it was approved by Cleveland City Council, finalizing the team's relocation to an enclosed stadium complex in Brook Park.

It marks a likely end to 30 years in downtown Cleveland for the Browns after the mayor and council ardently fought for over a year to keep the team in the city-owned stadium.

The agreement includes a $100 million commitment from the Haslams to pay for the demolition of the existing stadium, as well as tens of millions toward community projects and lakefront development in the next decade. In exchange, the city and HSG will drop their lawsuits.

The Haslams will also pay $25 million upfront days after council's approval.

"This is really a win for the city; we think what we have here is a deal that is historic," Law Director Mark Griffin said. "Instead of us paying to subsidize professional football, they're going to pay us."

The deal did not go without changes from council, which rigorously vetted the settlement over several hours-long hearings. That included an amendment to budget $25 million specifically for city neighborhood projects, funneling some dollars away from downtown lakefront. That's a 25% increase from the original $20 million community benefits proposal.

Additionally, the term sheet now requires that at least 30% of the business contracts related to stadium demolition be Cleveland-owned. 20% of contracted work must come from small and minority-owned businesses. Both figures are higher than the city's typical requirement for such projects, according to the Bibb administration.

Some council members still opposed

Bibb, who has taken political blows from several members of council over the settlement, defended the deal, saying he took council's direction to make sure the city didn't leave empty handed.

“For the last three years, this administration has worked hard to deliver a deal we believe works for the taxpayers in all of your wards, all our wards," said Bradford Davy, the mayor's chief of staff. "We have done that, plus.”

The deal was approved by a 13-2 vote with two members absent. Mike Polensek and Brian Kazy voted against the measure. Some council members said they were "blindsided" by Bibb's October press conference announcing the settlement without consulting the legislative body.

“I couldn’t even hold out my nose and vote for this," Polensek said. "There will not be one dollar of improvement going into St. Clair Superior, Glenville, Collinwood, Euclid-Green. There will not be a dollar going into those neighborhoods … out of this deal.”

City officials say council will have input on mutually agreed upon community benefits projects funded by the deal, which can be anywhere in the city.

Former Cleveland mayor, council member and state representative Dennis Kucinich, who is also filing another lawsuit on behalf of taxpayers, came before council Monday to urge members to take more time before "rushing" approval of the deal. He told council members the deal was "financial malpractice."

"This will have an impact on the Guardians and the Cavs because if there's no way to protect the city's interests, then you can kiss those teams goodbye too," he said. "Don't tell me it can't happen."

Mark Griffin said he doesn't believe Kucinich's taxpayer lawsuit has merit.

Some members criticized the mayor for not getting more or accused him of rolling over to the billionaire owners, but Mark Griffin and external experts said the city's hands were bound and officials had no real leverage after the team's lease expired in 2029. Griffin said any legal opinions in the city's favor could only delay the inevitable departure for the team, whose owners are now backed by $600 million in state funds to pay for the new $2.4 billion stadium.

"So, whether we pass this or not pass this, they're still gone?" asked Council President Blaine Griffin.

"That is correct," Mark Griffin confirmed.

He said the city has already spent upward of $1.5 million to litigate the lawsuits, one of which Griffin said may be weakened because of the state's recent gutting of a rarely used law intended to keep teams in taxpayer-funded facilities. If the lawsuits proceeded, he estimated an additional $1.5 million in fees next year.

Even some of those who voted in favor of the settlement said they were doing so begrudgingly. Council Member Kris Harsh said it seemed like the mayor was "giving up," but said he would not risk a taxpayer responsibility to tear down a stadium the city could no longer use when the Browns leave.

"I know we've been talking a lot about telling the Haslams to kick rocks," Harsh said. "But I think if the administration is resigned to this ... it's our fiduciary responsibility."

What happens to the downtown stadium next?

The Browns will play at least two more seasons downtown before the team's lease expires.

The team has two, one-year options to renew their lease as part of the original contract, but then city officials say that's the hard stop, even if the $2.4 billion Brook Park stadium is not yet complete.

Mark Griffin told council Monday the city has now added new terms to that lease renewal; an additional $1 million toward community benefits projects for the first year and $2 million the second year.

In the meantime, the city has contractual obligations to perform repairs to the stadium that ensure fan safety. City officials say they will not approve any "unnecessary" renovations to the stadium.

Once the team vacates downtown Cleveland, the Haslams will pay to raze the stadium and prep it as a shovel-ready site for future development. That project has an estimated $30 million price tag, but the city confirmed the Haslams will pay any overage.

Then, the city will get moving on its sweeping, decades-long lakefront master plan, which now includes a task to fill the hole left by the stadium.

Earlier this year, Bibb put out a request for proposals for developers to pitch ideas for 50 acres of lakefront land, which included the stadium site.

A developer has not yet been selected.

A park, which was already planned for the areas surrounded the stadium, has been pitched in various meetings to fill the site.

What else is in the deal?

Shortly after the lease expiry in 2029, the team will pay the city $5 million per year until 2033, totaling an additional $25 million.

The agreement also stipulates that upon the lease termination, the Haslam Sports Group will invest no less than $2 million per year over a decade to a mutually agreed upon community benefits project (totaling no less than $20 million). That has now been negotiated up to $25 million, per council's request, funneling some payments away from the lakefront.

In exchange, the city will support the "continuing progress and timely completion" of the Brook Park stadium, although the amended term sheet stipulates that comes at no cost to the city.