With relocation plans to Brook Park firmed up, Cleveland officials say the Browns will get the boot from the Downtown stadium after the NFL team's lease ends.

The lease, which expires after the 2028 season, includes two one-year options to renew. But after that, in 2031, city officials say the team would be out — even if the multi-billion stadium complex in Brook Park is not complete.

"Obviously it'll be assessed at that time, but there's a hard stop after two years," said Mark Griffin, the city's law director. "We want certainty on the lakefront. We want to know that we can move forward on that. And so, you know, our view at this time is they need to be done after two years."

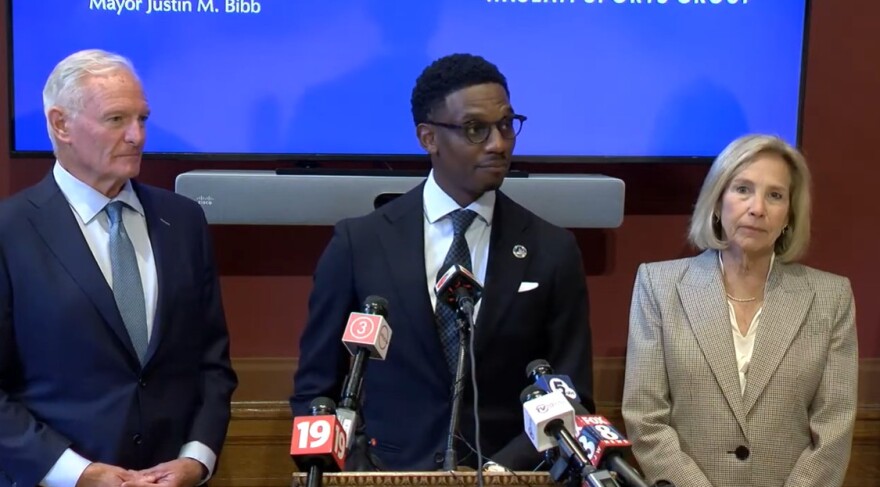

This comes a month after Jimmy and Dee Haslam struck a $100 million agreement with Mayor Justin Bibb, who relented on his years-long campaign and incentives to keep the team Downtown. In exchange for hefty investment promises from the pair of billionaires, Bibb said the city will drop its lawsuits against the team. The Haslams will do the same.

Part of that settlement includes a commitment from the Haslam Sports Group to raze the existing stadium and assure its site-readiness for future development — which could include a park and recreational green space on the lakefront — at an estimated cost of $30 million. City officials clarified in a presentation to council on Monday the Haslams have agreed to cover associated costs beyond that.

But it's not yet a done deal: though Cleveland's law director has discretion over the status of city lawsuits, council is responsible for approving key elements of the settlement, including accepting donations and approving demolition.

Council again vetted the proposal in a hearing several weeks after grilling Bibb over the deal — and members gave the administration an earful.

"We collectively cannot continue to make bad decisions around this," said Councilmember Mike Polensek, who represents the East Side neighborhoods of Collinwood and Glenville. "I've been here long enough to see a lakefront line that goes to a parking lot that nobody wants to ride, to building a hotel downtown with no parking, losing a jail with 400+ jobs to Garfield Heights, the Browns leaving for Brook Park, schools about to be closed that will devastate our neighborhoods. ... I see nothing before us that tells me anything about stabilizing our city, specifically the east side of the city. Nothing."

Despite opposition, Bibb and other members of the administration have defended the deal. The team's owners, which have reportedly poised the proposal as a "take it or leave it" offer to city officials, have long-signaled they planned to relocate to their own stadium, and Bibb said there's nothing the city can legally do to get them to stay beyond the lease expiration.

Even if the city continued to pursue its suits that accuse the team of violating the lease and a rarely-used state law, Bibb said there is no guarantee courts would rule in the city's favor.

He said if the team was going to leave regardless, he wanted to make sure the city was not left empty-handed. Bibb's deal secures an upfront $25 million payment by Dec. 1, as well as millions in investment to the lakefront master plan and community benefits projects across city neighborhoods.

Even still, council members again dug in Monday. Some weren't happy with Bibb, who insisted he could've "gotten more" from the deal, while others expressed concern over what they see as an "enthusiasm" for Downtown lakefront development over other neighborhood issues.

"It is very difficult to get the administration interested, in my opinion, in kind of routine stuff in the neighborhoods," said Councilmember Charles Slife, who represents the far West Side neighborhoods of Kamm's Corners and West Park.

Slife said he's concerned about how the expected annual loss of $30 million in indirect economic activity will affect not only Downtown, but the rest of the city's neighborhoods.

"If we are not recouping anywhere near $30 million, how is our general fund going to be able to simultaneously absorb a large park and its maintenance needs alongside all of the other routine things that occur across the city of Cleveland?" Slife said.

Members of the administration assured Slife that while some of the Haslam's investment dollars will fuel lakefront development, others will be funneled directly into the neighborhood projects for capital investments, recreation and education. They also argued green space is economically viable: not only does it bring visitors Downtown, they say it's a way to entice private developers for future investment.

"It's important to note that those will happen throughout the city, not simply on the lakefront," said Bradford Davy, the mayor's chief of staff.

Polensek and Councilmember Brian Kazy, outspoken critics of the settlement proposal, said they plan to vote no on the legislation as it stands. Others also indicated hesitancy.

The final deal is coming before council for approval by Nov. 24. If members fail to act before then, the administration said it could delay the $25 million upfront payment.

In the meantime, the three lawsuits between the city and team remain active.