Editor's Note: This story was originally published on Sept. 27, 2016, and is being republished with minor updates following the death of Cuba's Fidel Castro.

How's this for historical coincidence: Fidel Castro and his rag-tag fighters assembled in Mexico, navigated an overcrowded boat to Cuba, and unleashed a 1956 insurgency that spawned countless imitators in the decades that followed. On Thursday, Colombia and the FARC rebels signed a deal to end the last major leftist uprising in Latin America — one day before Castro died.

Castro's Cuban revolution set the tone for Latin America, where authoritarian governments, often led by generals, battled leftist guerrillas in most every country at some point over the past half-century.

Colombia's agreement this week was a do-over that illustrated how elusive peace has been in Latin America. President Juan Manuel Santos first signed an agreement with the rebels in late September, but Colombian voters narrowly rejected it in an Oct. 2 referendum.

The deal was amended, and this time it will be voted on in Congress, where Santos' coalition holds a majority and is expected to approve it.

"As president of all Colombians, I want to invite all, with an open mind and open heart, to give peace a chance," Santos, the winner of this year's Nobel Peace Prize, said at the signing ceremony with the rebel leadership in the capital Bogota.

The goal is to bring peace to a country that has endured more than a half-century of civil war. Widely overlooked is the far more sweeping notion that it would bring down the curtain on six decades of nonstop conflict in Latin America.

To take an even broader view, there's no longer a single war in the Americas, a collection of more than 30 countries stretching from the Canadian Arctic to Tierra del Fuego at the bottom of South America.

Of course, the absence of war isn't necessarily full-fledged peace. Mexico still suffers chronic drug violence, as do several other countries. The Central American nations of Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador are riven with gangs responsible for some of the highest murder rates in the world. Venezuela is wracked by political turbulence. And even as Colombia's main guerrilla group agreed to lay down arms, a separate, much smaller rebel faction carries out the occasional attack.

Still, Latin America, long plagued by autocrats, coups and endless civil wars, now has a moment worth savoring. Elections and peaceful transfers of power have steadily become the norm.

"The region has made tremendous progress from 20, 40 years ago," said Richard Feinberg, a professor at the University of California, San Diego, who closely follows Latin America. "On almost every front — politics, economics, social programs — we've seen vast improvements."

Here's a condensed look at 60 years of war and peace:

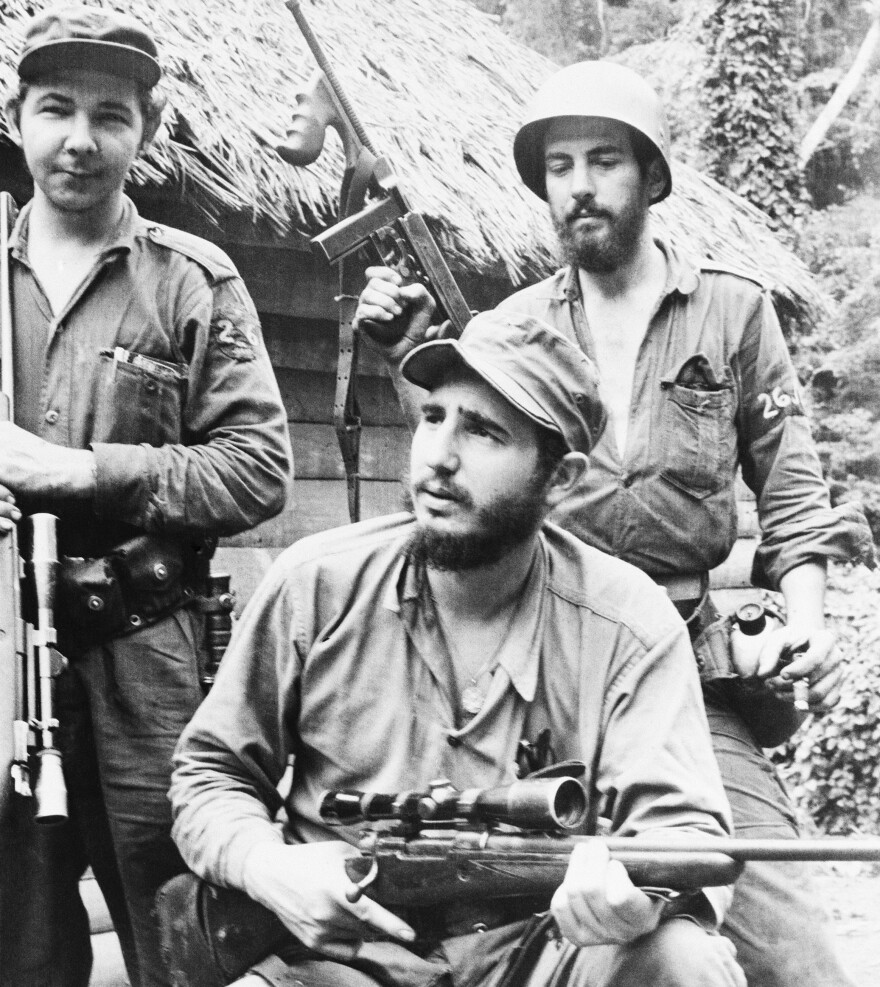

Castro Fires The First Shot:The Cuban revolution wasn't the first uprising in an unstable region, but it did mark the dawn of a new era that had major ramifications all across Latin America.

Castro inspired many who adopted his leftist politics and sought to oust authoritarian rulers, many of them strongmen who seized power through coups. They tended to represent the military and the tiny elites who dominated politics and business.

Cold War politics drove the U.S. to support pro-American rulers, even outright dictators, while the Soviets looked for additional opportunities to expand their influence. In this bipolar world, there was little, if any middle ground. Genuine democracy and competitive elections simply weren't part of the equation.

"The U.S., the Cubans, and sometimes the Soviets would be feeding these conflicts with ideology, money and weapons," said Feinberg, author of the recently published Open For Business: Building The New Cuban Economy. "All these international actors were polarizing, and you didn't see any change in their behavior until years later, when the Cold War was over."

A Region Aflame:At the peak in the 1970s and '80s, nearly every country in Latin America had a guerrilla movement, and some had more than one. (Special mention goes to Costa Rica, the only Latin American country that doesn't have an army and is generally regarded as the only one that hasn't had an insurgency in the past 60 years.)

During the 1980s, in particular, the U.S. was deeply involved in Latin American conflicts. The U.S. removed the leaders of Panama and Grenada during brief invasions. Washington backed the right-wing government in El Salvador in a vicious fight with left-wing guerrillas. The U.S. funneled arms to pro-American rebels in Nicaragua battling the left-wing Sandinista rulers.

Most Latin American civil wars were waged at a relatively low level, with bands of rebel fighters using small arms to wage hit-and-run attacks from rural hideouts. Yet the collective impact on these impoverished nations was often devastating.

Latin American governments poured limited resources into the security forces. The fighting ravaged rural areas in countries heavily dependent on agriculture. Right-wing and left-wing ideologies dominated, drowning out moderate voices. These civil wars had the nasty habit of dragging on indecisively for years, often decades.

Colombia's civil war offers an extreme example. It erupted in 1964, has involved multiple rebel groups, and claimed more than 200,000 lives. The weakened country was also vulnerable to the emergence of drug cartels, which in the 1980s and '90s arguably posed a greater threat than the civil war.

Yet in all these years of Latin American warfare, only two rebel groups ousted rulers by force: Castro's fighters toppled Fulgencio Batista in Cuba and the Sandinistas brought down Anastasio Somoza in Nicaragua in 1979.

"Revolutions are extremely hard to pull off," said Feinberg. "Most attempted revolutions fail miserably at tremendous cost to everyone involved. Conditions are rarely there for violent overthrows. For starters, you need to be facing a very decrepit regime."

The Cold War's End Eases Tensions: The end of the Cold War rapidly reduced regional tensions, led to peace treaties and elections, and helped create the space for Latin American countries to work out protracted feuds.

Nicaragua held an election in 1990, which the Sandinistas lost. El Salvador made peace in 1992. Guatemala followed in 1996.

One-by-one, the generals faded away and in many countries, former rebels did better at the ballot box than they had on the battlefield.

In Uruguay, El Salvador and elsewhere, former rebels won elections. Brazil's Dilma Rousseff, who was jailed for three years and tortured as a member of a guerrilla group in the 1970s, was elected president twice, once in 2010 and again in 2014. She was, however, impeached in August on corruption charges, a move her supporters called a "coup."

Politics in Latin America is still a rough business. But these days, it's no longer waged with guns.

Greg Myre is the international editor of NPR.org. Follow him @gregmyre1.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxMzY2MjQ0MDEyMzcyMDQ5MzBhZWU5NA001))