More than 100 million people are expected to watch the first debate between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump on Monday night, potentially the largest audience for a campaign event in American history.

Why?

What do we expect from this 90-minute faceoff? A watershed moment in our history? A basis on which to choose between the candidates? Or just a ripping good show?

Obviously, many of us hope to get all three.

[The debate from Hofstra University in Hempstead N.Y. will be broadcast live on NPR beginning at 9 p.m. ET with Robert Siegel as host of the special coverage.]

The 2016 campaign has already been remarkable in many ways. But the most stunning departure from precedent may well have been the lacerating exchanges among the rivals in the Republican primaries.

The altered mood of those GOP debates stemmed primarily from the high-impact, freewheeling style of Trump, who brought his bruising "reality TV" persona to bear on his biggest stage yet. Previous matches had featured a jab here and a sharp elbow there, but nothing like the roundhouses and haymakers thrown by Trump and his rivals.

Dismissed initially as a political neophyte, the newcomer dominated the debates en route to collecting the most delegates.

The Democratic primary debates also grew heated as that contest became more competitive in the spring, but they never approached the GOP fracas in either personal vitriol or TV ratings. Clinton's main challenger, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont, was criticized for taking the issue of her private email server off the table in the first debate. ("People are sick and tired of hearing about your damn emails.")

But if their internal debates were relatively tame, the Democrats have since matched the GOP in full-throated and pointed attacks. The two national conventions were each devoted largely to denunciations of the November opposition.

Since then, both Trump and Clinton have dismissed each other as unqualified and unfit for the office, a species of political criticism usually assigned to running mates, campaign surrogates and staffers. In this case, the role "attack dog" has also been taken up by the principals themselves.

So on Monday, many people tuning in will expect a flurry of punches by high-volume and highly antagonistic combatants. After all, such an extraordinary campaign seems bound to produce an extraordinary debate. But do not be too surprised if it turns surprisingly serious and even flirts with being staid.

It is entirely possible that Trump and his team will see it in their interest to project the more presidential-looking image the candidate has achieved at some recent events (such as his whirlwind visit to Mexico City). If we see a more sedate Trump, it is likely Clinton will follow suit, rather than seem temperamental or emotional.

On the other hand, Trump seemed to signal quite a different approach on Saturday, sending a Twitter message saying he might bring Gennifer Flowers to the debate. Flowers is the Arkansas woman who held a news conference during the 1992 presidential contest to say she had had a 12-year affair with Bill Clinton.

On Sunday, Trump's campaign manager Kellyanne Conway told ABC's This Weekthat the campaign had not actually invited Flowers to the debate.

How Do the Candidates Prepare?

Candidates have traditionally gone on retreat to study for the debates, poring through briefing books prepared by staff. In recent cycles it has become customary for the campaigns to put on "mock debates" so the candidate can practice lines against a stand-in version of the opponent.

The New York Times reported over the weekend that Philippe Reines, a longtime Clinton aide, would "play Trump" in practice sessions for the Democrat. The Trump campaign has not announced a corresponding stand-in for Clinton, nor has his campaign acknowledged it is holding mock debates at all.

The campaigns also engage in pre-game spin regarding the relative readiness of their candidate. They each insist that the playing field is not level, but they disagree on the direction of the tilt.

This "expectations game" is the inverse of the bragging and posing boxers do at their weighing-in ceremonies. Campaigns lavish praise on the debating prowess of their opponents –insisting that their own contestant is the underdog.

Thus in the current contest, Trump's staff and surrogates have cast Clinton as a professional politician with decades of experience and debating practice. Just holding one's own against her would be terribly difficult for anyone, they say, let alone an outsider such as Trump.

Correspondingly, the Clinton camp has insisted that she is a reserved sort of person who is not inclined to bombast or verbal duels. It is Trump, they say, who has the advantage after years of rehearsal on reality TV shows such as The Celebrity Apprentice.They also argue he proved his extraordinary powers by mowing down all his Republican primary rivals on live TV.

How Much Do Debates Matter to the Election?

Social scientists have produced data suggesting that past debates have not made a major difference to the standing of the candidates, with "post debate bumps" proving minor and temporary. But the popular impression persists that the debates were either a turning point in an election (as when John F. Kennedy outshone Richard Nixon in 1960) or a tipping point (as when Ronald Reagan's performance in 1980 seemed presidential enough to win over doubters, just before Election Day).

In any event, the televised debates provide the one most dramatic and telegenic moment of the year after the nominating conventions. They are also usually the only time the major candidates appear together or question each other. And the enormous TV audience lends a sense of do-or-die pressure well beyond any other moment in most campaigns.

If 100 million do indeed watch, one tends to think they will include most of the people who will actually cast ballots this November. The biggest turnout in raw numbers for a U.S. presidential contest was in 2008, when more than 130 million people voted for Sen. Barack Obama of Illinois over Sen. John McCain of Arizona. Turnout was down slightly in 2012.

Have There Always Been Debates?

In 1964, 1968, and 1972 the League of Women Voters wanted to sponsor debates but the candidates of the major parties did not reach an agreement to debate. In two of these years, 1964 and 1972, the incumbent presidents (Lyndon B. Johnson and Nixon) were cruising to landslide re-elections.

The debates came back in 1976, when incumbent Gerald R. Ford was trailing Democratic challenger Jimmy Carter and saw the debates as part of a comeback strategy. Ford wound up losing by just 2 percentage points, and some believed his awkward description of Poland's relationship with the Soviet Union (which was still occupying Eastern Europe at the time) caused him to fall short.

In 1980, Reagan was overtaking the incumbent Carter when they had their lone debate, scheduled just a week before the election. Reagan's confidence and charm were enough to close the sale. They were enough again in 1984 when, after a weak showing in the first debate, Reagan returned to form in the sequel and sailed to a 49-state re-election.

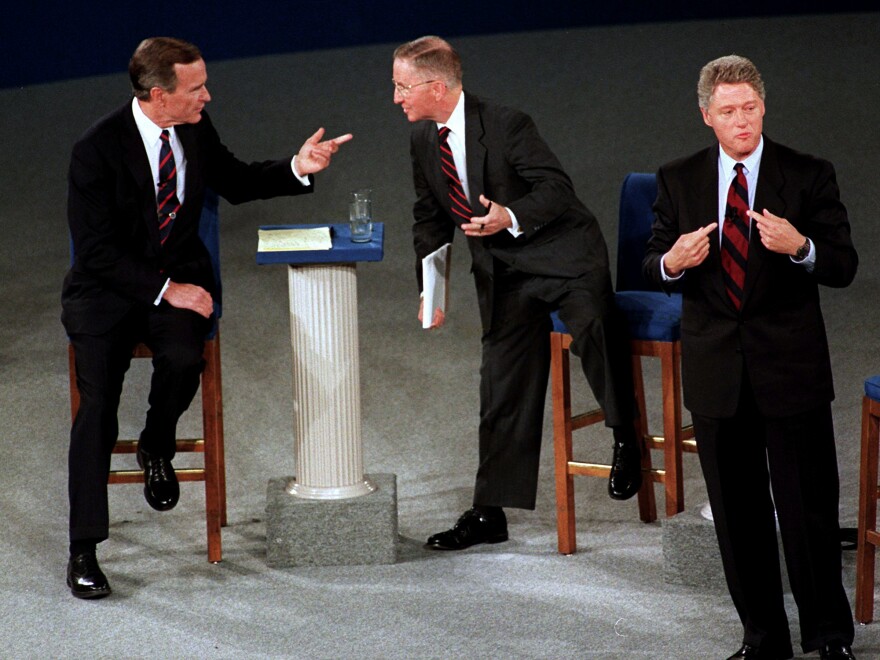

In 1992, President George H.W. Bush found himself on stage with not only Bill Clinton, the Democrat, but independent Ross Perot as well. Those two kept up a crossfire on the incumbent, who did not help his case by seeming somewhat detached and even checking his watch.

In 2000, the main stylistic issue involved Democratic nominee Al Gore, whose eye-rolling and audible sighs seemed meant to denigrate his opponent, George W. Bush. But Gore's behavior proved distracting to many, and Bush himself was unfazed. Bush also surprised many who expected him to suffer by comparison to Gore, a more experienced debater.

Who Actually Runs the Debates?

From 1960 through 1984, the debates were staged by the League of Women Voters, which was regarded as non-partisan. But controversy arose over some of the positions the League had taken on issues such as abortion rights and the Equal Rights Amendment. So in 1987 the two major parties established a Commission on Presidential Debates (CPD). Beginning in 1988, the CPD organized each set of debates, negotiating with the TV networks and the campaigns and helping choose the moderators.

Trump called @LesterHoltNBC a Democrat. Not so. NYState voter form shows Holt, moderator of Monday's debate, is a registered Republican pic.twitter.com/XzoVYU9es8

— David Folkenflik (@davidfolkenflik) September 20, 2016

The moderator has often been a source of contention, as neither party wishes to have its candidate grilled more harshly or cast in an unfavorable light. For several cycles, the PBS anchor Jim Lehrer was the most frequent choice, viewed as even-handed by both parties. Longtime TV newsmen Tom Brokaw of NBC and Bob Schieffer of CBS have also filled the role, as has Candy Crowley of CNN.

On Monday night, the moderator will be Lester Holt, the anchor of the NBC Nightly News. Holt has not been seen as a controversial or overly-editorial figure, although some eyebrows were raised when Trump said "Lester is a Democrat." It turns out that Holt has been registered as a Republican in New York for more than a decade.

Were There Debates Before 1960?

The Kennedy-Nixon debates were the first between major party nominees to be televised and are considered the beginning of the modern era of presidential debating. The first was held on Sept. 26, exactly 56 years before the Clinton-Trump meeting. Popular assessments at the time had Nixon winning if you heard the debate on radio, Kennedy prevailing if you saw it on TV.

The most famous antecedent is the legendary series of hours-long matches between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas. At the time, the two were running for a Senate seat in Illinois, which Douglas won. Two years later, they squared off for the presidency and Lincoln became the first Republican to occupy the White House.

An attempt to revive that tradition was made in 1948, when New York Gov. Thomas Dewey debated Minnesota Gov. Harold Stassen in Oregon, prior to that state's important Republican primary. The event was probably most important in that it drew an enormous national radio audience, greater in percentage terms than the audience expected for Clinton-Trump.

In 1956, ABC televised a debate between former Illinois Gov. Adlai Stevenson and Tennessee Sen. Estes Kefauver, rivals for the Democratic party nomination. They faced off in a debate in Florida before the primary there, and wound up being the Democratic Party ticket that fall (losing to incumbent President Dwight Eisenhower).

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxMzY2MjQ0MDEyMzcyMDQ5MzBhZWU5NA001))