Everywhere you turn, it seems, there's news about the human microbiome. And, more specifically, about the bacteria that live in your gut and help keep you healthy.

Those bacteria, it turns out , are hiding a big secret: their own microbiome.

A study published Monday suggests some viruses in your gut could be beneficial. And these viruses don't just hang out in your intestines naked and homeless. They live inside the bacteria that make their home in your gut.

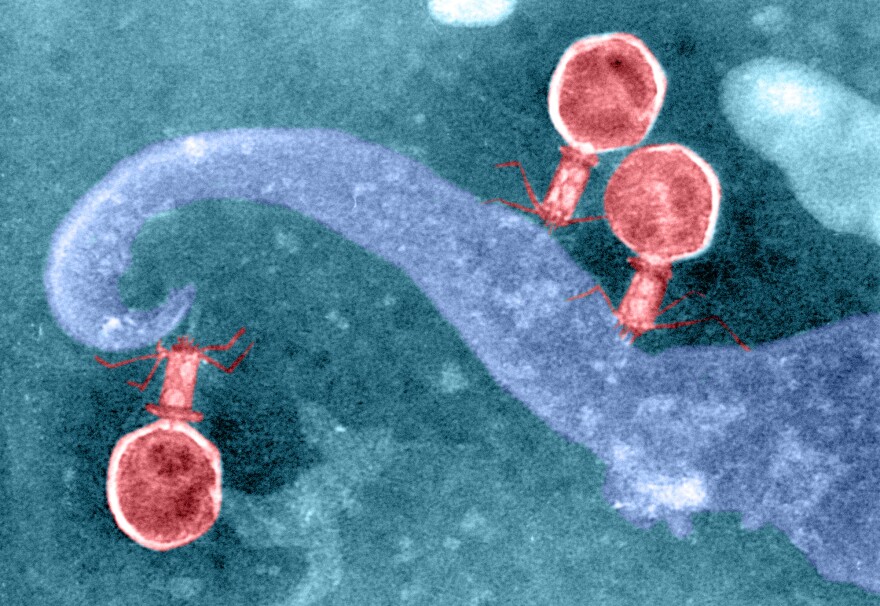

These particular viruses are called bacteriophages. And, until recently, many scientists had sort of ignored the ones in the gut, says Mark Young, a virologist at Montana State University. Researchers didn't have good tools to study these phages, Young says, and understanding them hasn't been a priority, because they don't seem to cause problems.

"Most virologists are looking at how viruses cause disease," he explains. "We're flipping that around, and looking at the possible role for viruses in promoting health."

To begin their study, he and his team sequenced the genes of bacteriophages found in the guts of two people. They combined their data with evidence from a previous study, which had sequenced bacteriophages in more than 160 people from the U.S. and the U.K.

In the larger data set, about a third of the people had healthy guts. The others had a chronic intestinal illness — either Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis.

From the combined group of people, Young and his team identified 23 bacteriophages that seemed to be associated with a healthy gut. These viruses were common in more than half the healthy people and were much less common in people with Crohn's or colitis, the team reports this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"We speculate — and clearly at this point, it is speculation — that these viruses help maintain your health," Young says.

Their conclusion is still speculative, he explains, because he and his team can't tell from their work whether the bacteriophages are contributing to a healthy gut or are just a result of that health.

Plus, the team's study was small, and it didn't look at a diverse group of people, says Jonathan Eisen, a medical microbiologist at the University of California, Davis who studies gut microorganisms and wasn't involved in the research.

"It's cool that the study found these common viruses in people," Eisen says. "But the caveat is that they really didn't survey the human population broadly. They didn't survey indigenous populations, [for example, or] people of different age groups and genders." What each person eats might have an influence on these viruses, too, Eisen says.

"There's incredible diversity among the viruses in our guts — way more diversity, actually, than you see in the gut bacteria," Eisen says. "It's this amazing, amazing world that has, so far, not been studied in a lot of detail."

Some scientists suspect bacteriophages may determine which bacteria get to dwell in the gut and which ones aren't allowed to stay, Eisen says. Bacteriophages are potent assassins.

"Bacteriophages can take over a bacterium," he says, "make a lot of copies of the virus, burst out of the cell and kill that cell."

Doctors may one day be able to turn that behavior to their patients' advantage, Eisen and Young say. Though researchers still have a long way to go in figuring out how all this works, we may one day be able to fight bacterial infections with viruses.

"That's certainly one of the avenues we're exploring," Young says. "We're certainly hoping that's the case."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxMzY2MjQ0MDEyMzcyMDQ5MzBhZWU5NA001))