It is 2015, and jetpacks do not fill the skies of cities, nor are giant space colonies in orbit around Earth, their inhabitants dining on hydroponically grown crops. Nevertheless, we in the affluent West are still living in the future – the future of food.

I don't mean the bag of Soylent that sits on my kitchen cupboard shelf, a kind of dare from a friend ("see if the food writer will eat this"!). Nor am I talking about laboratory-grown meat, pizza vending machines or genetically modified plants and fish.

I mean that, from the standpoint of the year 1900, we in 2015 in some ways are living in an age of unforeseen bounty. We're the beneficiaries of food production technologies – and a wealth of delicious and formerly exotic ingredients – our ancestors could only dream about. In the U.S., we have access to more calories, and by and large, more nutritious calories, than past generations; our food-related diseases are related to cheap industrially produced foods (think diabetes and sugar; think heart disease and meat).

But this future we live in is quieter and less showy than what previous generations of inventors and innovators dreamed up. That's because a great number of their foods of the future never came to be. The following list of the failed future foods of the past comes, in part, from Warren Belasco's important book Meals to Come: A History of the Future of Food and from Matt Novak's blog . As Belasco puts it, "History is littered with the debris of projects that were theoretically possible but economically impractical."

Totally Synthetic Food: The 19 th century French chemist Marcellin Berthelot proposed that we create "chemical food," doses of nitrogen and carbon that would supply the same nutrients as, say, a beefsteak. In 1896, an article in the Indiana Progress packaged Berthelot's claims for an American audience: "When the era of chemical food comes, we shall have done with symposia and supper parties, Welsh rabbits and golden bucks." While he was a pioneer in the synthesis of organic chemical compounds, Berthelot's beefsteak tablets never materialized.

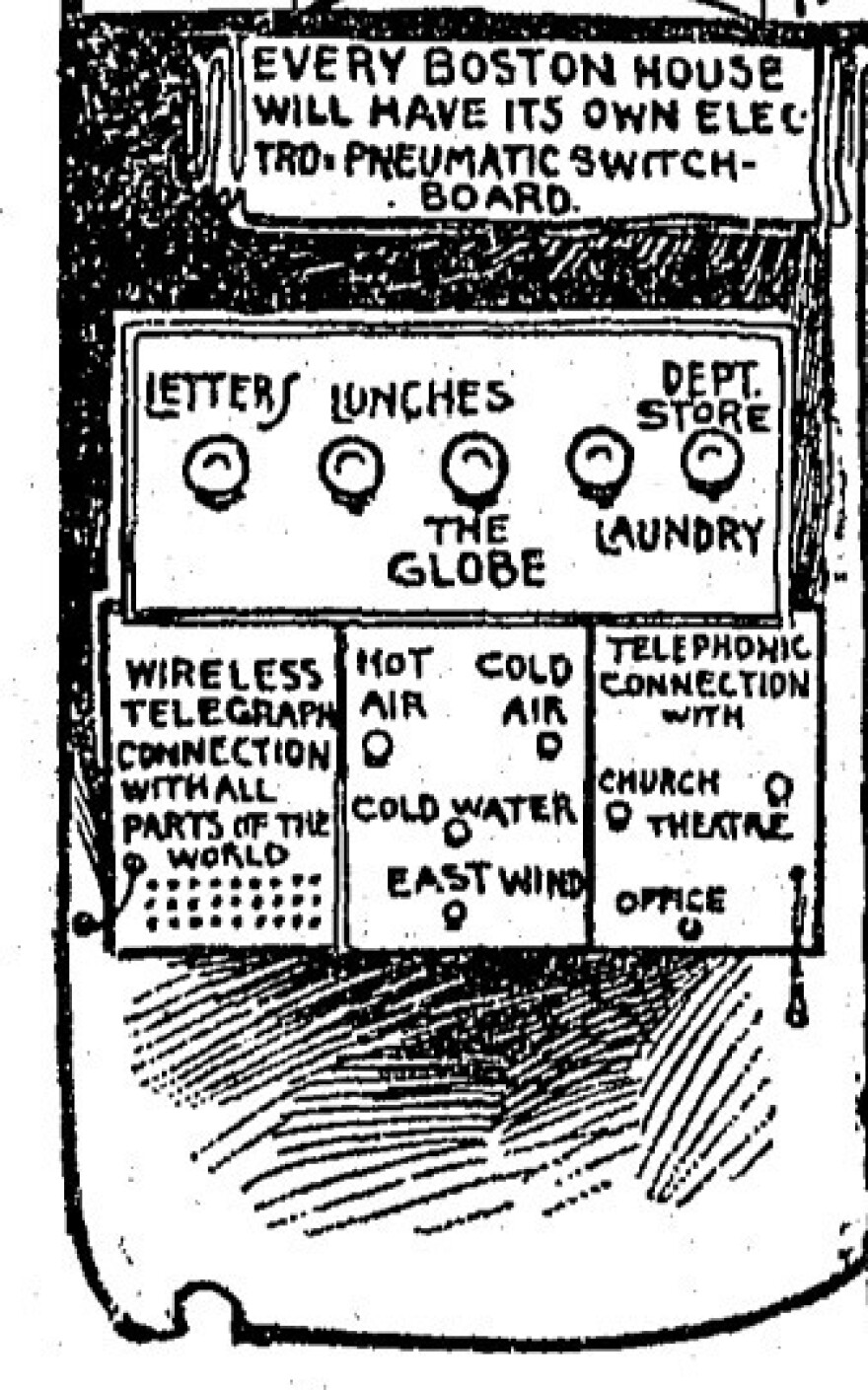

Food Delivery By Pneumatic Tube: in 1900, a Boston Globe article depicted a future in which there would be home delivery of food through tubes. While a McDonald's location in Edina, Minn., used the technology to deliver food to cars in its drive-thru, the technology never caught on.

A Vegetarian Diet:Because they used the beefsteak as a measurement of the healthy human diet, many nutritionists and demographers in the 19th to the early 21st century predicted that population growth would eventually lead to less meat to go around. As we know, meat production has soared and widespread vegetarianism has not come to pass. In both the developed West and in developing countries worldwide, meat consumption continues to increase — only in the richest countries are we seeing a small decline in meat-eating, often linked to health concerns rather than supply.

More Totally Synthetic Food:Berthelot's late 19th-century fantasy found a successor in the 1953 book The Road to Abundance, which dismissed the ideal of "natural" foods and promoted the idea that food was, at base, just chemicals. Berthelot had already supplied Western imaginations with the dream of the food pill, which would be visible in The Jetsons and 100 other pop culture forums.

Giant Vegetables:Many of our current crops are giant versions of the ancestor plants from which they were bred – and that's not even counting these supersized cabbages and turnips grown for competition in Alaska. However, many have fantasized about increasing the size of tomatoes, corn and other plants to monstrous sizes for decades. The Giant Vegetable (or Fruit) trope can be seen, signifying abundance, in such places as Arthur Radebaugh's Closer Than We Think, a comic of the late 1950s-early 1960s.

"Protein from the Sea:"In the 1950s, a type of algae called Chlorella pyrenoidosa, which grows quite quickly and is more efficient at converting sunlight to protein than most crop plants, seemed like an appealing solution to the problem of population growth and limited farm acreage. Predictions in the media of "farms of the future," just offshore of the California or Texas coast, or of chlorella burgers, came to naught, however. Competitor crops such as soy were produced in greater abundance than expected, while Chlorella production turned out to include unanticipated technical challenges and thus additional costs.

That didn't stop director Michael Anderson from satirizing the dream of replacing land-based animal agriculture with more efficient and less wasteful oceanic agriculture in the 1976 film version of Logan's Run.

Chlorella, though, is seeing a revival today. As The Salt has reported, a number of new startups are developing microalgae food products they hope can compete with plant-based proteins like soy.

Veggie Burgers:The idea of replacing meat with vegetable proteins – not out of love for animals but to make better use of farmland – is an old idea in the food futurism world. Another Closer Than We Think strip from 1958 drew from the work of biologist James Bonner. He imagined what the strip called "fat plants and meat beets" — crops designed to supply the necessary nutrients for veggie burgers. Of all the ideas on this list, it is the only one to come to pass, albeit not quite as Bonner or Radebaugh would have expected.

Instead, chefs like Dan Barber in New York are reinventing veggie burgers with beet and celery pulp, while Silicon Valley startup Impossible Foods claims to have invented a plant-based burger in the lab that tastes just like meat.

And so we see that the shiny objects of food futurism – new sources of protein designed to fix social or environmental problems and that seem to ask for a leap of faith from the general public – rarely work out in the way intended. Instead, additives and novel ways of raising crops sometimes do. Margarine and saccharine, for example, were once "foods of the future," and so was the synthetic fertilizer we now depend upon.

Containers and packages, too, were once cutting edge: The aluminum can, now an invisible part of our everyday lives with food, was once heralded as a world-changing new product. The success stories in the history of food's gradual modernization, turn out to be less flashy, but more far-reaching in their effects and implications.

Benjamin Aldes Wurgaft is a writer and historian. His essays, reviews and criticism — such as this essay on writing in cafes — can be found in theLos Angeles Review of Books, Gastronomica and other publications. He has several books in the works.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxMzY2MjQ0MDEyMzcyMDQ5MzBhZWU5NA001))