It's a warm evening at Tia Chucha's Bookstore in Sylmar, in California's San Fernando Valley, not far from the neighborhood where Ritchie Valens created a rock 'n' roll version of the most famous son jarocho tune "La Bamba." Tonight, Aaron Castellanos is one of eight students in a music class held at the store. He's learning to play the eight-string jarana, the main instrument in the musical style of son jarocho.

"I like the way that the jarana sounds," he says. "I like how son jarocho invokes so much energy into the playing and into the singing."

Students learn the jarana in a Son Jarocho class at Tia Chucha's Centro Cultural & Bookstore in Sylmar, Los Angeles.

"This is the first instrument that I've ever learned, so I want to keep playing," Castellanos says. "I want to buy my own jarana and just continue practicing."

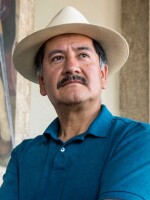

Castellanos' teacher is Cesar Castro, a key figure at the center of the Son Jarocho explosion in Los Angeles. Castro says that, since he moved to L.A. from Veracruz eight years ago, the number of son jarocho musicians has been growing, and the quality of the music has been improving.

"When we had the first fandangos here in Los Angeles, the music was not that good. But the energy, the will to do these fandangos, it was very strong," Castro says. "The music is getting better, still in a very respectful traditional format."

Fandangos are at the heart of son jarocho. They're kind of like jam sessions, where musicians gather to play, sing and dance around a wooden platform called a tarima. At the Zona Rosa Café in Pasadena, the fandango is hosted by Castro's band Cambalache, one of a dozen son jarocho groups in the L.A. area. Within an hour, more fandangueros arrive and join in, playing, singing and dancing.

About 10 years ago, Castro says, young Mexican-Americans got into son jarocho as a way to connect to their Mexican heritage.

"They felt more comfortable, more invited to participate," he says. "It doesn't matter if you don't dance, if you don't play, if you don't sing — you could be around it. It's a whole experience that people, little by little, got the chance to be part of and feel something good."

One of the groups that grew out of this evolving scene is the primarily female Son del Centro, an ensemble created at the Mexican Cultural Center in Santa Ana, the heart of the Mexican-American community in Orange County. All of the members sing, dance and play instruments. Member Ana Urzua says the music's ability to get everybody — musicians and audiences — to do everything is part of its appeal.

"It's a beautiful music," she says. "It's a music that is welcoming. But I think it's also that it is a part of something bigger. It's a part of a people, their traditions and their culture."

Los Angeles has been hosting a son jarocho festival for the last 10 years. This year, Mono Blanco, the group that helped revive this music in the late '70s in Veracruz, came to play in South L.A. Gilberto Gutierrez, the group's leader, says the traditional way of playing son jarocho has not changed. What's new and exciting is how young Latinos in the U.S. have taken up the music.

"The fandango celebration has the ability to bring together families, generations, different social classes ... and that's really positive," Gutierrez says. "Especially because these days, different generations tend to separate, but now suddenly there's an activity that unites the family: youth, old, kids, rich or poor and so on. I think that's what's been attractive to people here in the U.S."

Conjunto Jardin performs at a Son Jarocho event.

"If you become interested in son jarocho, you belong to a community almost right at the start," Figueroa says. "Of course, for us from Veracruz, it's important, but [also] for people from Mexico City, from California, like Chicanos, Anglos, whatever. They feel like they're participating, right from the start, in a community."

Libby Harding is the leader of a son jarocho group called Conjunto Jardin. When she was a child, she learned the music through her father, who learned it from the masters in Veracruz.

"I've always wanted to do it and share it with other people — share at least what I've learned and help maybe turn other people on to son jarocho by hearing us," Harding says. "Maybe they'd go and look at some of the roots of the music."

As long as son jarocho musicians learn and hold onto the roots of the music, the tradition will thrive wherever it's played.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.