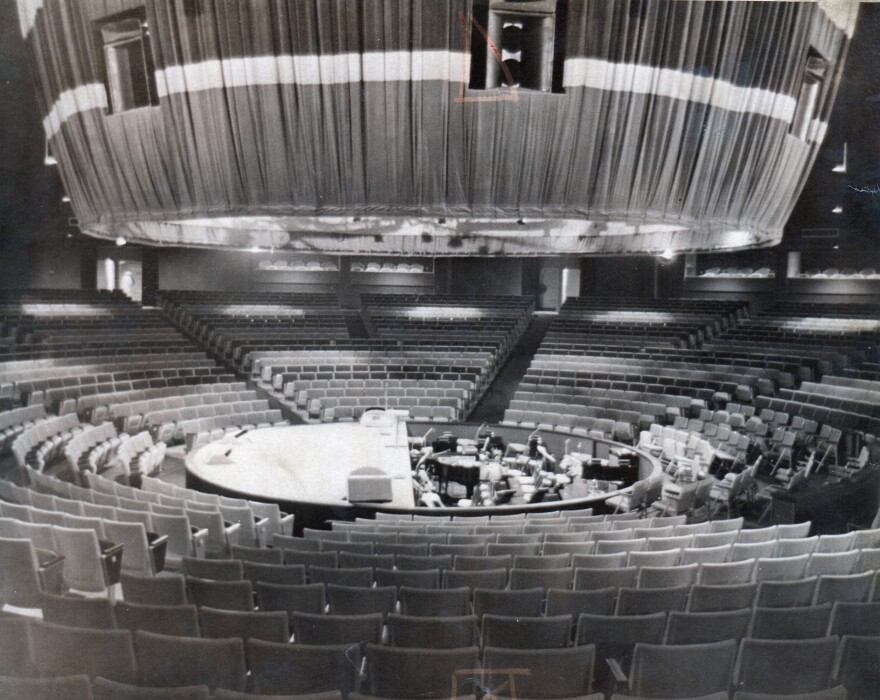

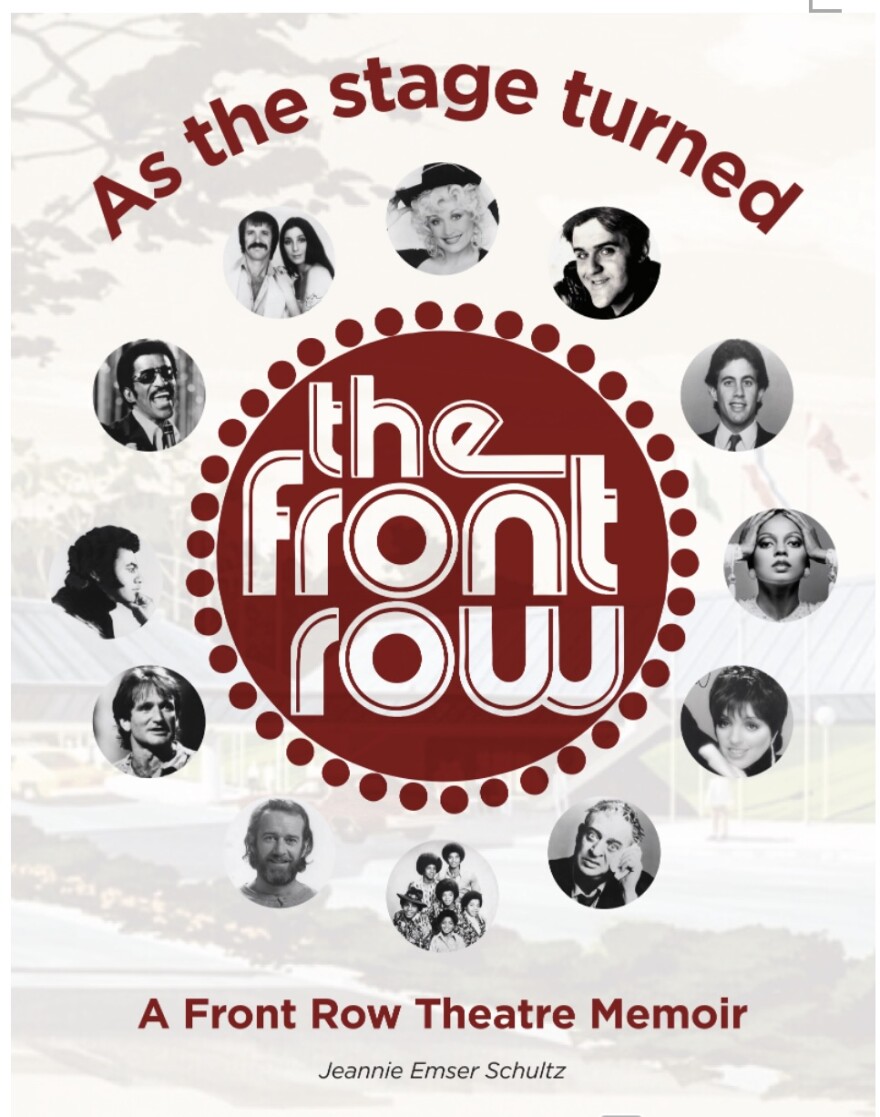

A new book takes a 360-degree look at a suburban Cleveland theater where every seat could be the best seat in the house. “As the Stage Turned: A Front Row Theatre Memoir” covers two decades of performers and politicians as seen through the eyes of the former venue’s director of marketing, Jeannie Emser Schultz.

“I started my career as a journalist and would do stories out in Los Angeles,” she said.

“I worked for the Plain Dealer. And because I did a lot of the interviews out in L.A., I was offered a job out there with a publicist. My friends in the media, of course, thought I went over to the dark side.”

Schultz returned to her native Cleveland in the early ‘70s, working for Belkin Productions and, eventually, the Front Row. When the theater-in-the-round opened in Highland Heights off Wilson Mills Road in 1974, the area’s venues were in a state of transition. Cleveland Municipal Stadium and the Akron Rubber Bowl were just stepping into the era of arena rock. Richfield Coliseum was about to open. The Cleveland Arena and Playhouse Square were flirting with the wrecking ball.

“We would do shows in the Allen [at Playhouse Square], but, after the rock concerts, plaster would be falling from the ceiling,” she said. “Those theaters were not yet renovated.”

Greater Cleveland’s concert cosmos expanded on July 5, 1974, when Sammy Davis, Jr. christened the Front Row Theatre.

“Opening night was really frenetic, because part of the parking lot wasn't done,” Schultz said. “Part of our liquor hadn't arrived yet, but people didn't care. It was really a big thing ... and that night had been a gala benefit to support University Hospitals.”

The show was not without its quirks: At one point, the stage stopped rotating. Davis eventually called out toward the control room, “I’m done with this side now!”

The rotating stage presented challenges for some comedians, requiring them to adjust to the venue.

“Imagine a comedian that relies on facial gestures,” Schultz said. “They would have to turn, as they were doing that, so that even though the stage was turning, it wouldn't be turning fast enough. So, you could hear the wave of laughter start at one point and move around the theater.”

Fans could sit extremely close to the action, as Robin Williams found out during a performance in the late 1970s.

“There was a lady pointing a camera at him, and he went over to her and he said, ‘Lady, what are you trying to take pictures of - my nose hair? Give me your camera,’” Schultz said. “He had those pants … that had the big elastic waist. He pulled the pants out, stuck the camera down into his crotch, and the flash went off. He took it out and gave it back to her and says, ‘Tell me how that one comes out.’”

Michael Jackson also learned of the potential pitfalls of a theater-in-the-round.

“There was a girl who ran out with scissors,” she said. “Of course, the security was on her. And here she didn't want to hurt him; she wanted a lock or Michael's hair. That was one of the security problems of having six aisles that came down to a stage.”

A week of tapings in 1979 for Phil Donahue’s television show required the stage to stand still. It also froze for Henry Mancini’s large orchestra and for Cary Grant’s 1986 speaking engagement – which led Schultz to a memorable photo op.

“As we were posing, he put his arm around my waist, and I said, ‘Mr. Grant, I'm going to blow this picture up life-size and put it behind my desk,” she said. “He goes, ‘My dear, you'll ruin your reputation.’ And I said, ‘I can't think of a nicer way to do that.’”

Grant passed away soon after appearing in Cleveland, as did another legend: Roy Orbison, who played his final show at the Front Row in 1988.

“He seemed larger than life,” Schultz said “He was very tall. He dyed his hair very black. One thing I remembered, and I don’t know if this had anything to do with his heart condition: He was just so, so pale. Almost like he’d used white powder on his face. And I thought, ‘Maybe that’s part of his black-and-white, yin-and-yang look.’”

Schultz, a night owl, usually began her day around 10 a.m. unless she was bringing guests to local morning TV and radio shows. Her day might not end until a post-show dinner, well after midnight. That was a problem in the early days of the Front Row, but some local restaurants and caterers eventually expanded their hours. Expanding local palettes, however, took a bit longer.

“I have a story about Oliver Stone,” she said. “When he came, Cleveland was not really into ethnic foods other than Slovenian and Czechoslovakia and Polish. We said, ‘What can we get you for lunch, Mr. Stone?’ He said, ‘Well, I’d really like some yellowtail sushi.’ Well, we didn't have any Japanese sushi restaurants at that time. By the time Tommy and Dick Smothers came in, Otani’s in Mayfield had opened.”

Other requests ranged from installing new toilet seats for Luther Vandross to ensuring that drinking glasses had no fingerprints for Patti LaBelle.

“A lot of people don't understand that a rider is really kind of a litmus test for the theaters,” Schultz said. “If they come in and … you have not accommodated them, then they think you have not accommodated them on other things too.”

Schultz recalled that Welsh superstar Tom Jones would visit every year and ask for a bottle of Dom Pérignon champagne after every performance.

“We never saw him drink it at the theater,” she said. “So, he left with eight bottles of Dom Pérignon. Unless he took it to the hotel, he has a wonderful wine collection at home.”

Some requests were more pedestrian but required some ingenuity. Comedian Don Rickles, for example, was hesitant to promote his appearances.

“Don wanted to sit in his underwear in the hotel and watch game shows all day,” she said. “Of course, he and Bob Newhart were great friends. Well, we hit on a lucky idea. I said, ‘When Bob was here, he did this.’ And he said, ‘Oh, did Bob do that? Oh, well, if Bob did it, OK, I'll do it.’”

Newhart himself nearly caused a disaster in the lobby while he was at the Front Row.

“They would always announce, ‘Five minutes, ladies and gentlemen, take your seats,’” Schultz said. “One night, a voice came on and said, 'Would the owner of the Buick, license plate number, etc., please go to your car? It's on fire.’ And everybody laughed because everybody recognized that voice: It was Bob Newhart. Well, not everybody recognized it, because somebody called the fire department. We had to explain it was a prank. They let Bob Newhart off, but they said, ‘Please don't do that again.’”

Along with colorful entertainers, newsmakers would take a turn on the stage in Highland Heights - everyone from Jimmy Carter to Gerald Ford to General Norman Schwarzkopf. Yet by the early ‘90s, the building was beginning to show its age. Schultz said the unique domed roof had been replaced twice, and owner Larry Dolin wanted to overhaul the building’s audio system.

“Playhouse Square had been courting us for about two years [to] come downtown,” she said. “And Larry really believed in Downtown at that time. The science museum, the Rock Hall, the new ballpark were all being built, and he felt that Downtown Cleveland was really where entertainment should be, and no longer in the suburbs.”

The Front Row Theatre closed June 26, 1993, after a run of sold out shows by Luther Vandross. The site was eventually redeveloped for retail. Since the release of her book, Schultz has heard from former employees who miss the camaraderie.

Shultz recalled the story of a former usher who spoke with her after a recent book signing.

"She lived near the Front Row and said when they tore it down, she just stood out there and watched them. And she cried because it was such a good part of her life,” Shultz said.

Schultz will be at Loganberry Books in Cleveland on August 3 as part of the Author Alley series.