In 2001, Macel Ely — the great-nephew of the late gospel singer Brother Claude Ely — went on a vacation to London. He went to a record shop and recognized the music being played over the intercom as his Uncle Claude's music.

Ely asked the store manager, "Are you playing Claude Ely's music?" The manager took Macel down the aisle to a display of Brother Claude Ely: a blown-up picture, and a selection of old 45s and LP albums.

Ely stood in the store for an hour, watching people coming in the store and buying his uncle's music.

"It really freaked me out, to be perfectly honest," he says.

Ely says he had grown up hearing his uncle singing and preaching and praying, and to him, it was just the same screaming and shouting that he had grown up hearing in church.

"I had no idea that outside of those Appalachian Mountains, people had heard about Brother Claude Ely," he says.

So 50 years after these recordings, Ely decided to find out who his great-uncle really was.

A Song On Claude's Deathbed

Ely began to drive through small eastern Kentucky towns, stopping in Pentecostal churches, knocking on the door and asking if there was anyone there he could speak to, and if he could record them.

And he would ask people, did you ever hear of a man named Claude Ely?

In all, Ely visited hundreds of churches over thousands of miles. Over nine years, he interviewed nearly 1,400 people.

Linda Morgan said she remembered meeting Brother Claude Ely at a tent revival in Cumberland, Ky. Others remember his singing.

When Brother Claude Ely would get up to sing, I mean he would just get a key on the guitar and when he started singing, it was like the heavens would open up.

Claude Ely was born in 1922 in Puckett's Creek, Va. When he was 12 years old, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and told that he was going to die as a child. His uncle Leander gave him an old guitar, which he would practice on his sickbed.

"Even as a child, he really had a very strong personal relationship with God," says Roberta Pratt, who was a member of the Cumberland Pentecostal church and knew the family.

When he was sick, Pratt says, Claude's family gathered in his room where he was in bed and prayed for him. And then, according to Pratt, Claude said, "I'm not going to die." And he started singing a song.

Ely says he learned that the family felt that God had supernaturally healed Claude. And they believed that God had given him a song: "There Ain't No Grave Gonna Hold my Body Down."

The song became an anthem among Pentecostal people in the Appalachian Mountains.

And it was one of the last recordings Johnny Cash made before his death.

The song was "just a plain, simple song that we'll never have to face eternity without God," says Terry Mont, who also knew Claude Ely. "It's a hope song."

Healing Powers

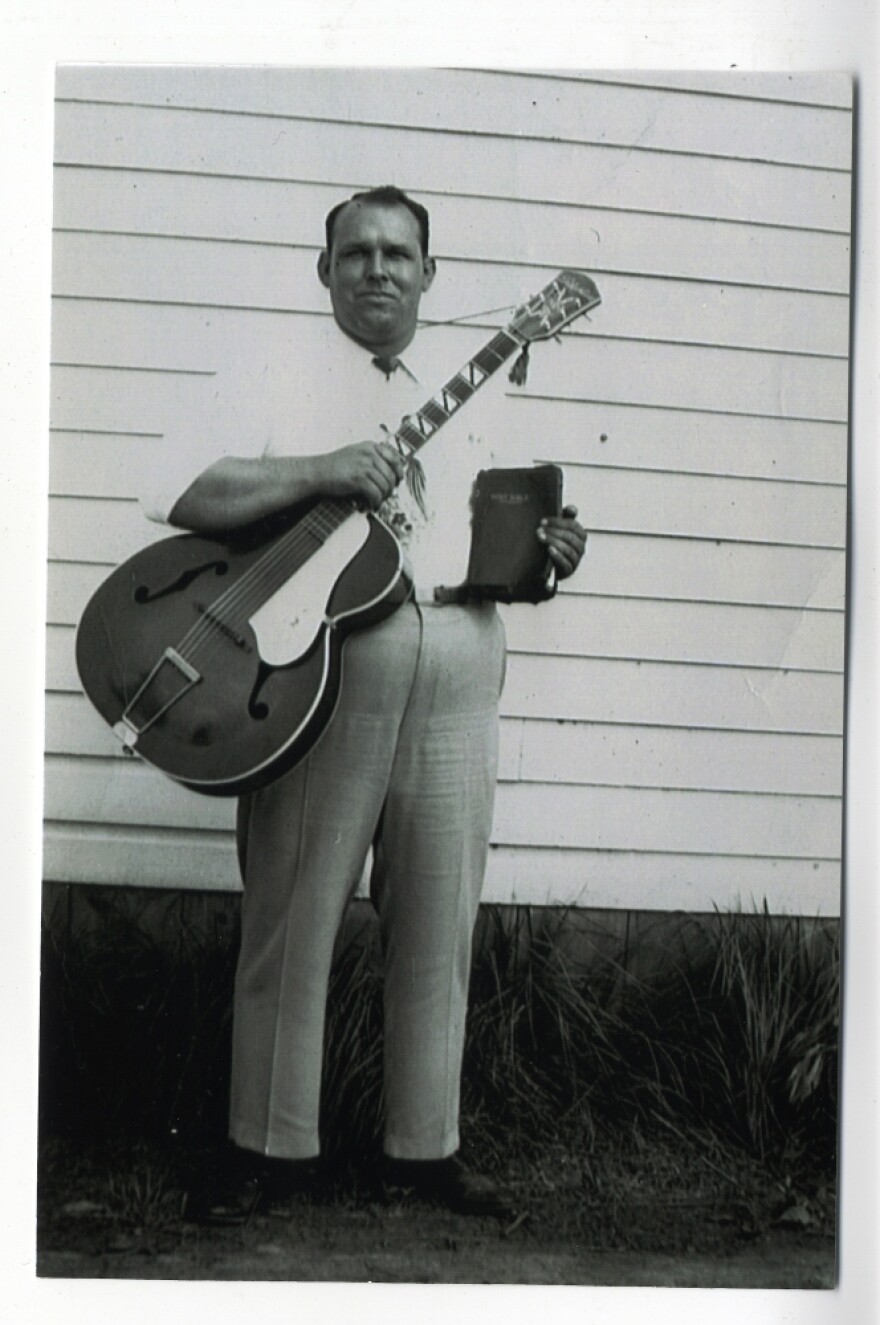

As an adult, Claude Ely went on the road. He traveled from city to city, wearing a cowboy hat and a white suit. He was a heavyset person, with a gold front tooth. His nickname was "The Gospel Ranger."

He would drive a car, steering it with one hand, and with the other he would announce with a bullhorn, "Later tonight at 7:00, I'll have a tent set up in the middle of town, please come out and experience the fire and Holy Ghost."

Mont remembers that the way Claude Ely carried himself, with an old guitar slung on his back, and a big smile. Claude Ely didn't disappoint anyone when he came to town.

Morgan recalls having trouble with her back as a child. She got in a prayer line at a Brother Claude Ely revival, and she says she was healed.

Dennis Hensley traveled with Brother Claude Ely, playing lead guitar for him in his revivals.

"When Brother Claude Ely would get up to sing, I mean he would just get a key on the guitar and when he started singing, it was like the heavens would open up," he says.

People would show up to revivals because they had heard about this country singer who sang like a black man. Brother Claude Ely would thrash his guitar, shake and gyrate from one part of the stage to the other. Young men would run up to wipe the sweat off his forehead.

Gladys Presley, Elvis' mother, was a fan of Brother Claude Ely's ministry, and some people remember Gladys and Elvis getting blessed at Brother Claude Ely tent revivals while Brother Claude Ely laid hands on them and prayed for them.

Kevin Fontenot, an expert on country music history at Tulane University, says that in 1953, King Records heard about Brother Claude Ely. The company decided to record him live at a Pentecostal service in the courthouse in Letcher County, Ky., when he was holding a revival. King Records set up equipment in the courthouse and made the initial recordings that made Brother Claude Ely popular. And Fontenot says that those recordings were a very valuable historical document because they were the first time people really got to hear a recording of a live Pentecostal service.

Pratt remembers that the courthouse was packed with people saying amen and clapping their hands.

"Pentecostals clap off the beat," she says. "We prefer our style of handclapping."

Fontenot says that it might be hard to tease out where different musical traditions come from. But he believes that Pentecostal music had an impact on rock 'n' roll. He says you can hear that impact in Brother Claude Ely's music.

Many of the early rockers — Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, and Johnny Cash — all grew up in the Pentecostal church, according to Hensley.

'Ain't No Grave Gonna Hold My Body Down'

Brother Claude Ely died nearly 33 years ago on May 7, 1978. He was playing the organ at his church in Newport, Ky. A tape recorder that someone brought to record parts of the service captured his death.

Brother Claude Ely started singing the song "Where Could I Go But To The Lord." Halfway through, he fell backward.

On the amateur recording, you can hear screaming and the moaning as people prayed for Brother Claude Ely. He died of a heart attack in front of his entire congregation.

Hensley notes that since Brother Claude Ely's death, there have been many artists who've recorded "Ain't No Grave Gonna Hold My Body Down."

"It just makes you feel good to know that a little country preacher from down in Virginia wrote that song," he says, "and it's pretty much went all over the world."

A few years ago, Macel went to the cemetery in Dryden, Va., where Brother Claude Ely was buried.

When he arrived, there was a handwritten note taped on the cemetery plot. It said, "Dear Brother Ely, You sung it and preached it to us. I know one day you'll come up out of this here ground. Thank you for being so good to us. It made a big difference and we won't forget it."

Produced for All Things Considered by Joe Richman and Samara Freemark of Radio Diaries. Edited by Deborah George with help from Ben Shapiro.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.