When Omar Mohamed was a boy living in the Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya, he loved picture books. But his school only had about three or four; the teachers brought them out for the children to read just a few times a year.

When that happened, it was a special occasion, says Mohamed, 31. "You read and you reread that book. Then you reach a point where you've memorized it."

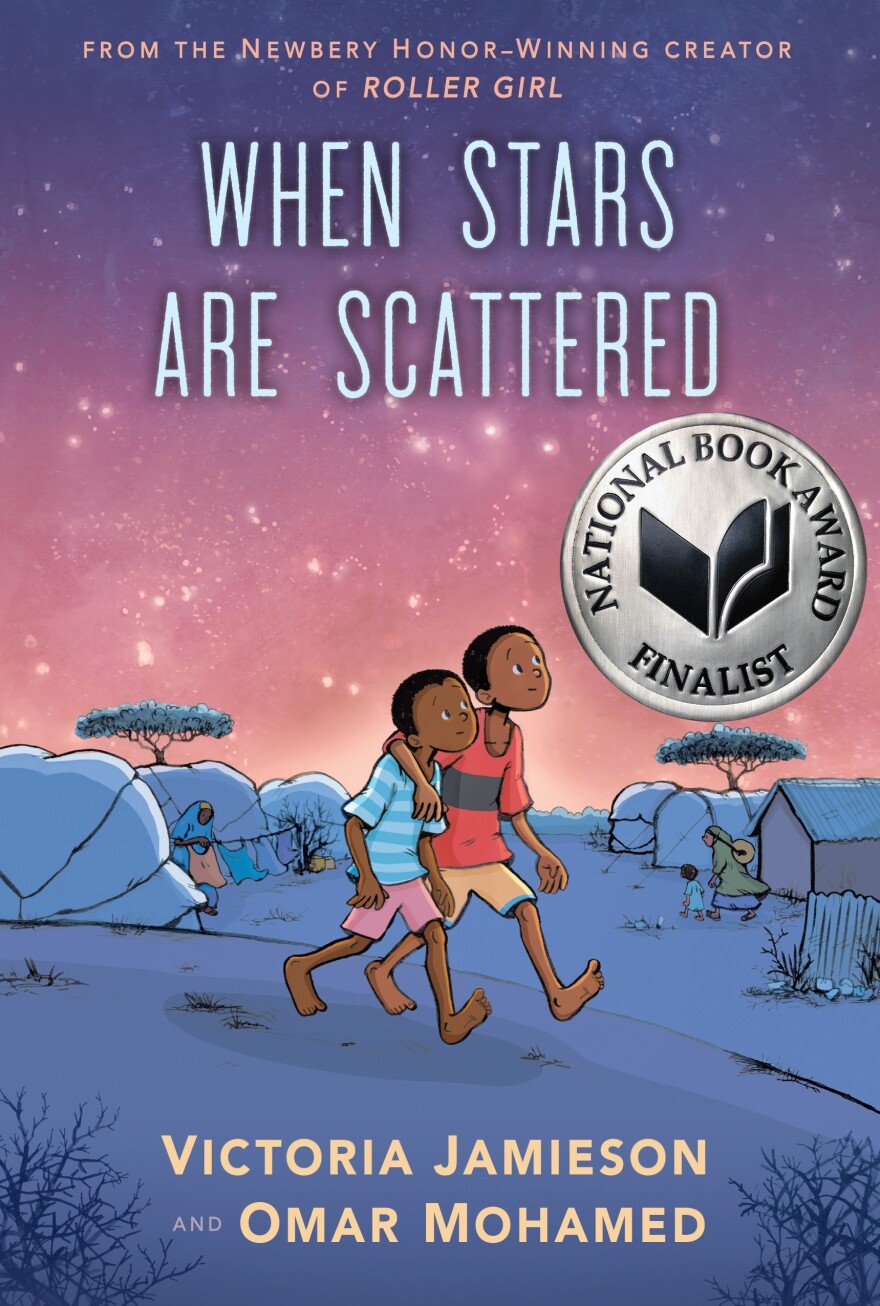

Now he's the star of his own picture book, the graphic memoir When Stars Are Scattered. He cowrote the book with Victoria Jamieson, who also illustrated the book, which has been met with acclaim. It was a finalist in the 2020 National Book Awards for Young People's Literature and in September was named a finalist in Publishers Weekly's annual Kids' Book Choice Awards in the graphic novel category.

The book, targeted to middle schoolers, covers Mohamed's life at the refugee camps up to 2009, when he and his younger brother, Hassan, resettled to the U.S.

The boys first arrived to Dadaab in the early '90s after the start of Somalia's civil war. Mohamed was 4 and Hassan was 2 when their village was attacked. In the chaos, the boys were separated from their three sisters and their mom. Their father had been killed by gunmen. A group of neighbors took them along as they fled to safety in Kenya.

At the camp, an elderly neighbor named Fatuma looked after the boys like a foster mom. As Mohamed grew older, he helped take care of Hassan, who has epilepsy and is nonverbal. He made many efforts to reunite with their mom. And he had to make hard choices about whether to go to school – and move with Hassan to a new country.

Today, Mohamed, 31, lives in Lancaster, Pa., with his wife, five children and Hassan. He helps resettle refugees in the U.S. for the group Church World Service and is the founder of Refugee Strong, a nonprofit that provides educational resources to refugee children in Kenya.

We spoke to Mohamed after his virtual book discussion at Cartoon Crossroads Columbus, an Ohio event that features comics artists, cartoonists and storytellers. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You met coauthor Jamieson while she was volunteering at Church World Service. How did that chance meeting turn into both of you working on this graphic novel?

I always wanted to write a book about refugee lives and I had a rough draft of my personal story already written. So I already had it good to go. Once I met Victoria and gave her the rough draft, she read it and convinced me to do it as a graphic novel since that's what she does.

That format was something new to me, so I didn't know what the outcome would be. But I like the way it came out — the pictures and the way it is illustrated — everything looks good.

Was it hard to tell your story with a collaborator from another culture? Did she capture the world of the camps in her art?

The experience was, in the beginning, kind of hard because I didn't know Victoria. She didn't know me, so it was learning about each other and trusting each other. She really did very, very well capturing the image of me and Hassan in Dadaab.

The story of how you escaped the war in Somalia and arrived to the refugee camps — by foot, without your parents — is heartbreaking. How is a journey like this, at such a young age, possible?

Our neighbors and friends in the village were fleeing, so we just fled with them. Kids like us and elders were transported on top of donkey carts, cows, camels or other animals.

The people who we fled with were mostly pastoralists [nomadic herders]. They knew the way to Kenya. They also took care of us.

It took us about two to three months to make it to the Kenyan border, where we were received by the United Nations at a refugee camp called Dadaab in a small town in the northeastern part of Kenya.

The title of your book, When Stars Are Scattered, refers to the comfort you felt looking at the night sky at Dadaab. You saw yourself and the other refugees as stars looking for a way home. Why did you need that sense of comfort at the camps?

Life was not easy. We call it an open prison. You're not allowed to travel outside the camp. To fetch water or go to the hospital, you always have to stand in line. Food distribution was every 15 days, but it was never enough. They only distribute maize, flour and oil. The first five days after food distribution — we call it the "happy week." Everyone is excited. By the next week, people are already running out of food.

What was the experience at the camps like for Hassan?

Hassan struggled. Kids picked on him because of his disability. If he wore shoes or shirts and he wasn't with an adult, the kids would steal them.

He got lost often. He likes donkeys and goats, and he would just follow them. Once Hassan stepped out of the compound and he didn't know his way back. So someone had to keep an eye on him 24/7. Fatuma supervised him when I was at school.

In your book, you say a turning point was going to school. Initially, you didn't want to go. You were worried about leaving Hassan alone all day. But eventually, you completed primary and secondary school at the camps. Was there someone at the school who had an influence on your life?

My principal. He was a Ugandan refugee and a good advocate for refugees to go to school. He and other teachers told me that getting an education was the only way out of my struggle and poverty — and the only way to help Hassan.

You also realized that resettling to another country could get you and Hassan out of the harsh living conditions of Dadaab, which is one of the world's largest refugee camps. One day at school, you met a U.N. social worker who took an interest in your story. How did that encounter help you and your brother leave the camps?

She worked closely with us on an application to resettle to the U.S. She knew that we were living by ourselves in the camp and of Hassan's medical [history]. The process took about seven years – and she continued following up on our case even after she moved to another country.

And you thanked her at the end of your book.

She really helped us a lot and pushed our case specifically.

After 15 years in Dadaab, you and Hassan resettled to Arizona. You were 19 years old. What did you do once you arrived?

After three months, I started working at a resort as a pool attendant. After one year, I went to the University of Arizona and studied international development with an emphasis on Africa.

Then in 2014, you both moved to Lancaster, Pa., because of its large refugee community. Hassan is enrolled in adult education classes and helps look after your kids. And you work as a case manager to help resettle refugees. Why did you choose that career?

I know the challenges that refugees face when they first come to America.

Can you give an example of that?

You're in a part of the world where race or skin color plays a big role. That is one thing we never talked about when we were growing up in that refugee camp. We were all Black. Everybody was of African descent, so we didn't talk about it, then for you to come to this part of the world — it's the main talking point.

One day I was helping a family of seven from Congo. I was in a big grocery store, showing them how to shop and how to use the grocery cart. And then this guy walking alongside us said, "You should go back to where you're from, you don't belong."

What did you do in that situation?

This has happened to me many times. But that time, I told him, "Your family came to the U.S. for the first time at one point — they just happened to come now. This country is not yours. It's not mine. It's everybody's."

What happened to the rest of your family members – your mom and your three sisters? Have you tried to reconnect with them?

My family is doing very well. My mom spent some time in Somalia during the civil war and then fled later. She is now in Kenya. She had heard rumors that me and Hassan were in Dadaab, so she went and met Fatuma – because by that time, we were already in the U.S. We reconnected with her through social media.

One of my sisters is at the refugee camp in Kenya and the other two are back in Somalia. We talk now.

Had your mom been looking for you the whole time?

We never spoke in detail about this, but she said she searched for us in Kenya in the years that we were separated.

Do you keep in touch with people who live in Dadaab? Is there an expectation that you will financially support them?

It's common for your friends at the camps to send you a message on WhatsApp and say, "I have this problem, this medical condition, my family is hungry."

I send about $500 a month to help my friends and family who are still living in Dadaab. Resettled refugees in the U.S. call it a "second mortgage."

For example, I send my sister $50 every month. I send Fatuma $50 every month. My distant cousin has a large family so I send him $70 every month. I also send another $70 to my former neighbors every month.

You can't miss one month, or people will get mad at you. They depend on that money to survive.

Did you ever think you'd be an author and the star of your own graphic novel?

Not at all. I never thought that. But it is a dream come true.

Jacky Habib is a freelance journalist based in Nairobi and Toronto. She reports on social justice, women's rights and global development. Follow her on Twitter @jackyhabib.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.