No matter where you’re paddling on the Mahoning River, you can count on seeing tires.

Many tires.

You’ll see them in the clear shallows and between fallen tree branches. They’ll be stuck in logjams and poking out of the mud. You’ll paddle over more tires you can’t see.

Some of those who want to restore the river spend a day each year working on the river, pulling out as many tires as they can.

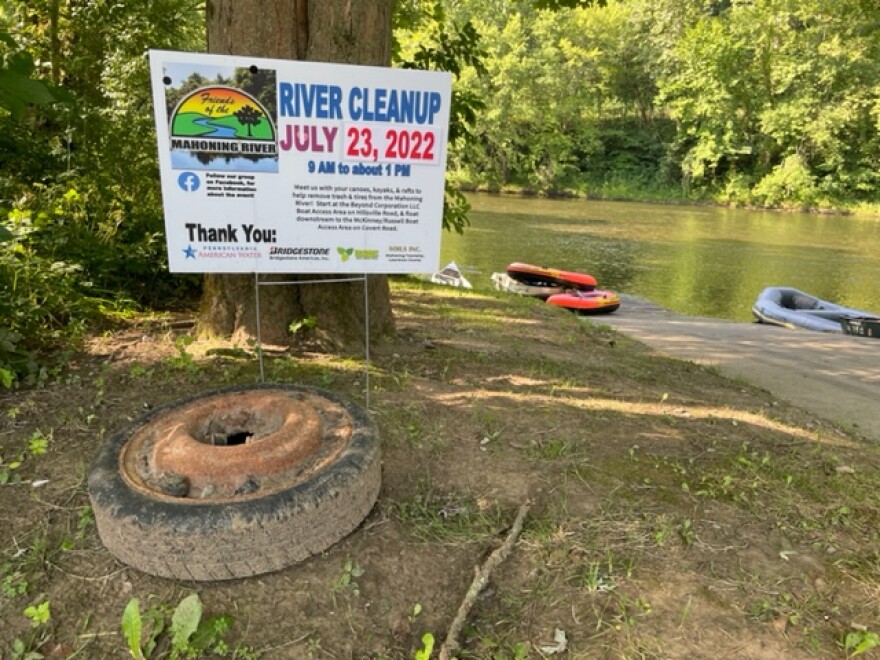

This year’s event begins at 9 a.m. on July 23. Volunteers gather at the boat launch in Hillsville, Pa., at the same dock where I launched for the first episode of this series. Now, like then, Tom Smith, board chair of Friends of the Mahoning River, is there. This is the third tire cleanup he’s organized.

“This started three years ago,” he says, “because when we were paddling the section of the river, my son happened to look down and saw a bunch of tires. And, [he said] 'Hey, Dad, we should probably do something about that since we're a river club.' [I said] ‘Yeah, you know what, you're probably right.’”

He reached out to some people he knew in Lawrence County, Pennsylvania. They contacted people they knew, and now there are several groups in two states cooperating on the cleanup, including local government agencies, nonprofits and businesses.

The volunteers know they’re in for a long, hard day. They brought some kayaks, a canoe and a small motorboat. Josh Boyle has provided the sturdiest watercraft here, a 1980s-era inflatable whitewater raft. At the first tire cleanup two years ago, volunteers were able pile about 10 tires in it at once.

The volunteers are wearing clothes they don’t mind ruining. Tom has brought them extra gloves, water — and donuts.

The volunteers I meet are regulars on the river, mostly paddlers. Raimon Schultz moved to the area from upstate New York.

“We have very clean water up there,” he says. “Since I've lived down here, I've seen the state of affairs, and it’s very, I won't say depressing. I have hope. But I think they still have a ways to go. So, if I can contribute, I try.”

Tom’s son Andrew — the one who gave him the idea to do a tire cleanup — is also here today.

Andrew has helped at all three of the cleanups, so he knows what’s in store for them.

“Well, usually we go in with a shovel or a pry bar to leverage the tire out of the river, out of the muck and mud, which is usually the worst part and backbreaking,” he says. “We do like a gold-panning, swishing-back-and-forth motion where we have to get all of the mud and dirt out because it gets the tire so heavy … and then we have to take it out to the drop off point.”

Around 10 a.m., the boats start launching from the dock.

For a while, I follow the small ragtag fleet in my car, while heading south along the road that runs next to the river. The volunteers don’t get far before they stop and start pulling tires out. I have no idea how long it’ll take them to get to the takeout point at Soils Inc., a family-owned mining business that sells specialty soil mixtures and other products in New Castle, so I just drive there.

I met Caleb Pierog, safety director and lab technician, at the dock, where he was coordinating with Tom. He told me Soils Inc. owners Wayne and Lynne Ryan would be happy to talk. Once I get to their property, I drive down a long, dirt driveway. All around, there are piles of what looks like gravel, dirt or sand, as well as the excavators needed to move them.

Soon after I park my car, Wayne walks over to say hello. He’s getting some work done while the tire cleanup crew works the river. He introduces me to his wife, Lynne, and soon, she’s driving me to the river in her rough-terrain vehicle. On the way, she tells me Wayne’s family farmed downriver from here, on property they’ve owned since the 1800s. His father started the mining business. Wayne and Lynne have been here since 1993.

“Ever since then, we’ve been buying up land that attaches to the property,” she says. “Crazy people.”

Owning about 5 miles of riverfront property isn’t easy. Sometimes the river floods and brings fish and garbage into their fields. Even garbage cans from the city of Warren have washed downstream in the rain.

At 11 a.m., on a beach formed after the last big flood in February, a crew of six in matching orange t-shirts are already pulling tires out of the river. Eight-year-old Jayson, the son of Heather Smith, who is training to be a lab technician, rolls a tire down the beach toward a giant excavator. Jayson is trying to earn his Cub Scout merit badges, and he’s struggling. But he keeps at it. At one point, he stops and puts a foot on the tire in triumph, smiling proudly.

“Even if there's 20,000 tires, even if it takes 20 years, it's better than just leaving it there. And I think that's something our area, the Mahoning River Valley, traditionally we did. We just moved on, and this is a way to just say, hey, let's remake this into something that is better than what it was.”Josh Boyle, river cleanup volunteer

Given the Mahoning River’s legacy of being polluted by the steel mills, I’m interested in hearing all that Soils Inc. is doing to protect it. In the past, mining companies have also polluted the river.

“We respect the river,” Lynne says. “We do not dump … We pay $15 more a gallon to use hydraulic oil that is vegetable-based, so that it can't contaminate any of the water sources for the wildlife. So, you know, we are very conscious of the environment, and we try to enhance it and protect it.”

On our tour, I learn that every pile on the property has a purpose. Some are destined for compost, specialty topsoil mixes, infill mix for baseball fields — or some other common material most people don’t think about much.

“When I first saw a sand and gravel operation, I thought I would never look at a bag of play sand the same again,” Lynne says.

The volunteers don’t get out of the river at Soils Inc. until around 5 p.m. The following Monday, Megan Gahring, treasurer of the nonprofit organization Tri-County CleanWays, and an associate collect the tires from all the designated spots on the bank. Then they drop the tires at Soils Inc., where Liberty Tire later moves them to a recycling center. That part is paid for through a grant from the Bridgestone Tire Foundation.

In 2020, the volunteers got 70 tires out of the river. In 2021, all the rain had made the river high and the tires hard to see. They only removed 58.

When I call Megan about this year’s haul, she tells me exactly how it stacks up.

“This year they got 183 tires,” she says, “which is tremendous.”

There are many more tires they didn’t get, and there will be more next year. Josh Boyle, the volunteer who brought the whitewater raft, says this doesn’t get him down.

“Even if there's 20,000 tires, even if it takes 20 years, it's better than just leaving it there,” he says. “And I think that's something our area, the Mahoning River Valley, traditionally we did. We just moved on, and this is a way to just say, hey, let's remake this into something that is better than what it was.”

After a summer of reporting from the river, I know there’s a community committed to its comeback. Some are working the tire cleanups. Some are writing grants, lobbying for funding, researching water quality or organizing people on social media. The best way forward isn’t always clear, and those who care about the river don’t always agree, but at least they’re talking.

This is a good thing for the Mahoning Valley, where many older communities — the mills and the union halls — are gone.

The river connects everyone, and it’s not going anywhere.