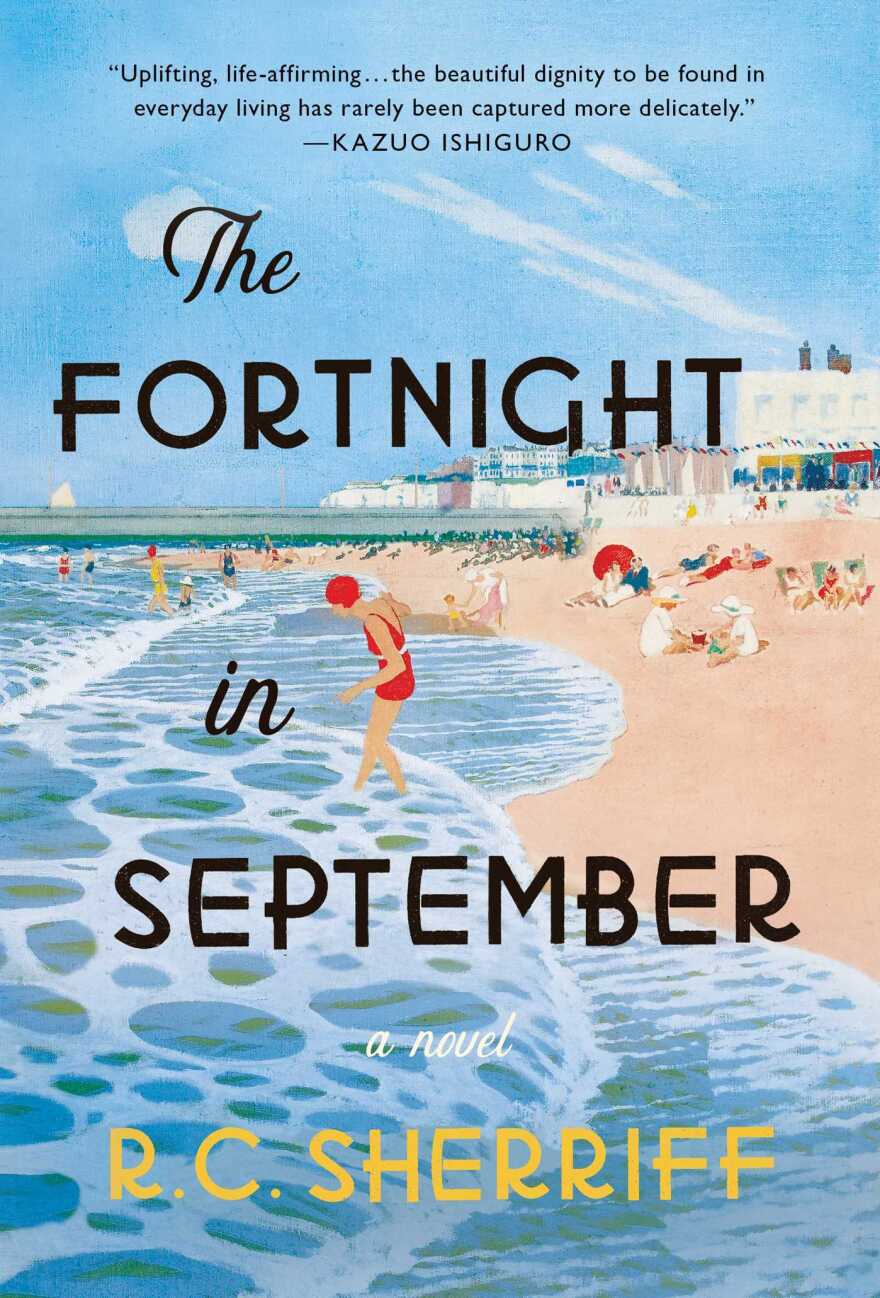

In the spring of 2020, the British newspaper The Guardian asked a group of prominent novelists, including Hilary Mantel, Marlon James and Kazuo Ishiguro to recommend books that would "uplift" readers and "offer escape" during the pandemic. Ishiguro proposed a 1931 novel called The Fortnight in September that he described as "life-affirming," "delicate" and "magical."

Fortunately, for readers who feel as I do — that when Kazuo Ishiguro raves about a novel, you'd be a fool not to pay attention — Scribner has just issued a 90th Anniversary paperback edition of The Fortnight in September. Of course, Ishiguro pointed us to a treasure, one that's been half-buried by the sands of time.

That powdery old metaphor is deliberate because The Fortnight in September is set at the seaside. It's about a lower-middle-class family, the Stevens, who live on the outskirts of London, making their annual two-week holiday pilgrimage to the coastal resort town of Bognor Regis. The parents, who, in the more formal custom of the times, are known as Mr. and Mrs. Stevens — first stayed there on their honeymoon at a guest house called "Seaview."

Over the years, that guest house, run by a proud widow, has become shabbier --its linoleum worn down, its sitting room infused with a "faint, sour atmosphere, as if apples had been stored in it." The Stevens' three children — Ernie, who's still a schoolboy; 17-year-old Dick, and 20-year-old Mary, who are both working — would no doubt prefer one of the newer "residential hotels that hung out fairy lights and blared their radio music across the roads." But, to make such a change would destroy the illusion of eternal return that visiting the same spot every summer conjures up: namely, that that place will always be there and so will you.

What follows, once the Stevens withstand the always stressful train journey, is a vivid compendium of moments semi-major and minor: Mary's first romantic cuddle with a young man; Dick's attempt to conquer the blues he's felt since starting work as a clerk, by walking vigorously on the beach; Mrs. Stevens' recurrent fear of the ocean and its "great, smooth slimy surface stretching into a nothingness that made her giddy." She keeps that fear secret, naturally, for the sake of the family. And, Mr. Stevens, in turn, keeps secret his annual visits to a pub, where the bold barmaid, Rosie, has always "brought him into pulsing touch with reckless instincts without the humiliation and danger of indulging them."

'The Fortnight in September' is an absorbing reflection on time and especially how it changes shape in periods like a vacation — or even a pandemic — that aren't bounded by normal routines.

There's enough period detail here to make readers feel as though we're relaxing with the Stevens in that sour Seaview sitting room: the "fruit salts," and "blue-tinted sunglasses" the family packs in their vacation trunk; the "steaming dish of chops and ... tureen of gravy" they sit down to for lunch. But beyond its Anglo allure, The Fortnight in September is an absorbing reflection on time and especially how it changes shape in periods like a vacation — or even a pandemic — that aren't bounded by normal routines.

There are so many passages in this novel where characters pull back and become hyper-aware of time. Here, for instance, is Sherriff's omniscient narrator commenting on the Stevens' arrival at Seaview:

They had reached the strange, disturbing little moment that comes in every holiday: the moment when suddenly the tense excitement of the journey collapses and fizzles out, and you are left, vaguely wondering, ... [w]hether the holiday, after all, is only a dull anti-climax to the journey.

You are, in fact, groping to change gear: you are running for a moment in neutral emptiness between the whizzing low gear of the journey and the soft, slowly turning high gear of the holiday — and in this moment of aimless uncontrol you are liable to ... say, like Mr. Stevens, rather lamely — "Well — here we are."

There's more than a dash of resemblance between The Fortnight in September and Virginia Woolf's time-conscious masterpieces, Mrs. Dalloway and To The Lighthouse, which were published a few years earlier. But, there's also a dash of Winnie-the-Pooh's Hundred Acre Wood magic here. Like R.C. Sherriff, Pooh's creator, A.A. Milne, served and was badly wounded in World War I. Little wonder then that, after the war, both traumatized men wound up creating tales set in time-out-of-time havens, where the small pleasures of everyday life — like honey, a hot bath and a clear blue early autumn sky — are seen for the gifts they are.

Copyright 2021 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.