The Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District will soon recommend removal of the Lower Lake Dam in Shaker Heights and Cleveland Heights, resulting in the draining of Lower Lake, replacing the lake bed with 17 acres of park land.

The district said draining the lake would prevent the risk of a catastrophic flood downstream along Doan Brook, the same reasoning it used in 2019, when the draining of historic Horseshoe Lake resulted in a furor in the East Side suburbs.

NEORSD’s recommendation is a 180-degree switch from its previously announced plan, shared in public meetings as recently as last October, to remove and replace the early 19th-century structure, with construction starting in 2027. That plan would have retained the 17-acre Lower Lake, a treasured regional amenity.

A district spokesperson said in interviews late Tuesday and Wednesday with Ideastream Public Media that the district has called an executive session meeting on Lower Lake at 7 p.m. on Aug. 11 with the mayors of Shaker Heights and Cleveland Heights, and the councils of both cities.

The City of Cleveland, which owns the dam and the lake and leases them to the suburbs, has not been included. Ideastream reached out to the city for comment.

“It’s still a conversation; no decisions have been made,’’ said Jennifer Elting, senior manager of communications and media relations at the sewer district.

Kyle Dreyfuss-Wells, the sewer district’s CEO, was traveling and was not available immediately for comment, Elting said.

Elting said that potential new modifications to the Wade Lagoon area, the pond that fronts the Cleveland Museum of Art in University Circle, could add flood control capacity to Doan Brook that would obviate the need to retain the Lower Lake Dam, about 2 miles upstream. The removal is also supported by new computer modeling of heavy water flow after storms, Elting said.

Jeffrey Strean, a consultant for the museum, said late Tuesday that the discussions with the sewer district are focused on adding a new Doan Brook culvert next to an existing one below ground, west of the lagoon, and would not affect the appearance of the historic landscape.

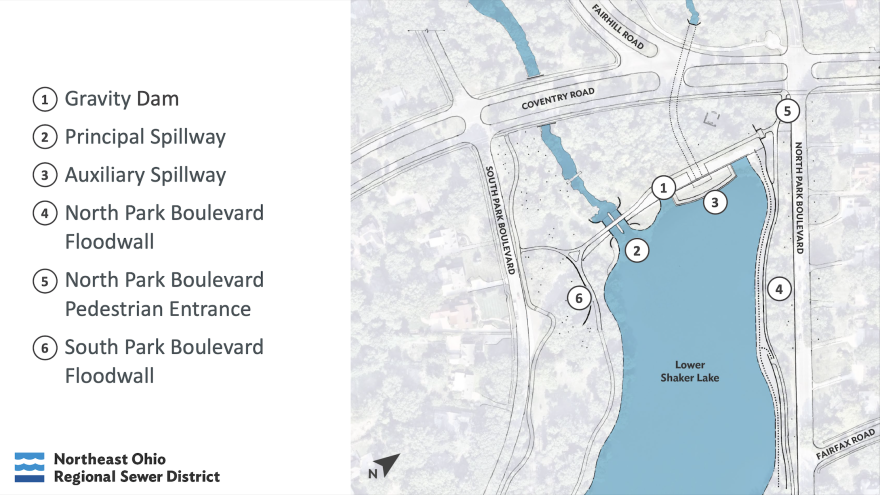

If the battle over the draining of Horseshoe Lake is any indication, removing the Lower Lake Dam will be controversial. Lower Lake, which straddles Shaker Heights and Cleveland Heights between North Park Boulevard and South Park Boulevard, just east of Cleveland at Coventry Road, has been a source of community enjoyment and pride.

Elting said that new cost estimates show that replacing Lower Lake Dam would cost $43.4 million, far more than the district originally estimated. Removing the dam and reconstructing Doan Brook in the lakebed as the centerpiece of a new nature park would cost $37.9 million, saving more than $5 million, she said.

If the Lower Lake Dam were to fail with water at the current level, it could cause $50 million to $80 million in damage to infrastructure and property, not to mention the potential for loss of life, Elting said.

Who owns what

Doan Brook and the surrounding park land is owned by the City of Cleveland and leased to the suburbs, which are obligated to maintain the dams. The brook rises in three branches that converge in Shaker Heights, flowing roughly 7 miles to Lake Erie at Gordon Park in Cleveland.

In 2019, the district drained 12-acre Horseshoe Lake, a mile upstream from Lower Lake, under an order from the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, which wanted to prevent the possibility of a catastrophic collapse.

Despite pleas from neighbors who posted “Save Horseshoe Lake’’ yard signs and wanted to see the dam replaced, the district decided not to do so. Instead, it developed a plan to turn the Horseshoe Lake area into a 60-acre park with no dam and a new channel through wetlands for the brook.

Construction of that park is scheduled to begin in 2026, Elting said. The project will cost $31 million, with $23.5 million coming from the district and $7.1 million from Shaker Heights and Cleveland Heights, she said.

The district oversees the Doan Brook drainage as part of its overall responsibility to manage storm runoff across its 363-square-mile service area in Northeast Ohio. It has spent more than $195 million over the past decade to reduce flooding and sewer overflows in the 12-square-mile watershed of Doan Brook.

No public outreach yet

Elting said the potential changes at Wade Lagoon and Lower Lake Dam have not yet been aired publicly, although she said the district will schedule public meetings in the future.

Despite the lack of public awareness, officials in Cleveland government are concerned.

In a July 10 email to city officials obtained by Ideastream Public Media, Susanne DeGennaro, Cleveland’s commissioner of real estate, said the city had received word from the sewer district that the Aug. 11 meeting is intended to explain its “current analysis on Lower Lake Dam.’’

DeGennaro said she would “ensure the District provides a similar opportunity for Cleveland officials as soon as possible.’’

DeGennaro sent the email to Mark Griffin, Cleveland’s law director, and Ward 15 Councilwoman Jenny Spencer in response to an earlier query from Spencer and a follow-up from Griffin expressing concern about the future of Lower Lake.

DeGennaro copied her email to City Council President Blaine Griffin, Chief Operating Officer Bonnie Teeuwen and Assistant Law Director Geraldine Butler.

Spencer’s initial email to DeGennaro noted that City Council had voted in July to approve dismantling the dam at Horseshoe Lake as part of turning the area into a park.

But she said she was concerned about the possible loss of Lower Lake and that she wanted the city involved at the beginning of any discussion about its future, not late in the process as was the case with Horseshoe Lake. She wrote that “dismantling of the Lower Lake Dam would be a catastrophic loss for the Shaker Lakes area and also for the nearby east side City of Cleveland neighborhoods whose residents recreate in this area.’’

Historic legacies

The North Union Shakers built the dams along Doan Brook in the 19th century to power a woolen mill, a sawmill and a gristmill in a settlement they called “The Valley of God’s Pleasure.’’

John D. Rockefeller donated Doan Brook and much of the land through which it flows to the city of Cleveland in the 19th century. The cities of Shaker Heights and Cleveland Heights grew up around the park land.

In the 1960s, a resident-led freeway revolt pressured highway planners to abandon designs for the Clark Freeway, which would have extended Interstate 490 east from East 55th Street in Cleveland through the Shaker Lakes to Interstate 271. The Nature Center at Shaker Lakes, built athwart the proposed right-of-way to help block the freeway, is a legacy of that era.

Elting said that the sewer district is now dealing at Lower Lake with the “same safety problems’’ it previously faced at what she Horseshoe Lake, which she referred to as Horseshoe Park.

Removing the dam at Lower Lake and allowing Doan Brook to flow without interruption would remove that danger.

“We are solid on our recommendation to the cities for this new direction,’’ she said. The cities — Cleveland Heights, Shaker Heights, and Cleveland, would have to concur — she said.