DAEGU, South Korea — On the right side of a narrow alleyway, a new mosque is under construction. On the left stands a tall display fridge with three pig heads inside, a resounding statement of opposition to the project.

The otherwise quiet alley in the city of Daegu is the front line of a three-year-long dispute between Muslim students of Kyungpook National University and residents in the neighborhood just outside the campus.

These tensions are proving to be a test of the nation's tolerance of increasing diversity, at a time when South Korea's leaders are looking to immigration to bolster the country's aging and shrinking workforce.

The Muslim community at KNU mostly consists of students from Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh and other countries with large Muslim populations. Its size fluctuates between 80 and 150 people, according to a community representative. The university's total student body is almost 27,000.

A space to gather and pray

In 2014, the Muslim students raised money for a place to gather and pray, bought a house near the university and called it the Dar ul Emaan Kyungpook Islamic Center. The house, just a few minutes' walk from the west gate of campus, was old and too small to accommodate the growing community, community members say.

So in September 2020, the students received permission from the local district office to construct an actual mosque on the site.

But a few months into construction, residents near the site filed a petition to the district office, claiming that the building would turn their neighborhood into a "slum." The district office immediately ordered a suspension of the construction, citing residents' "emotional instability, violation of property rights and concerns about possible slums."

This caught the Muslim community off guard. Students had gathered there for prayers five times a day for seven years with no explicit conflict with neighbors and did not expect their opposition to the new mosque.

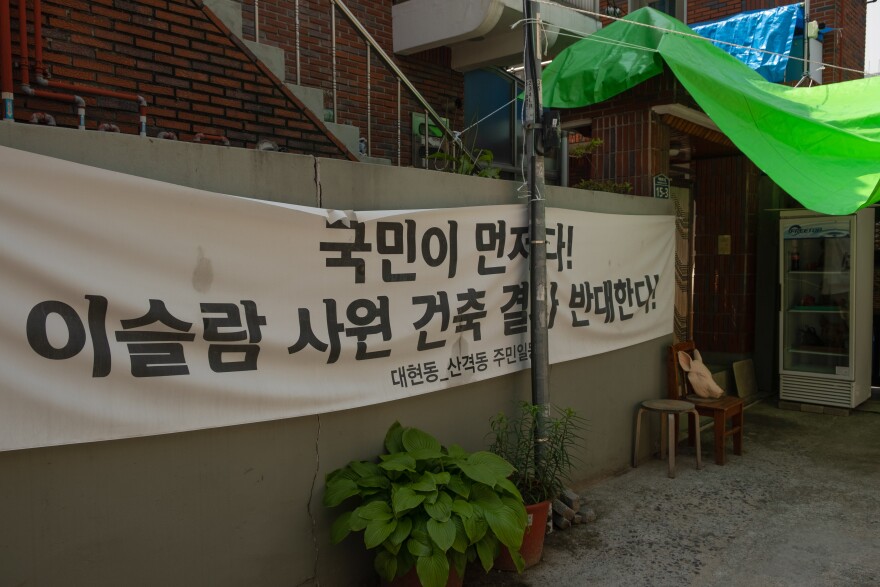

The Supreme Court eventually annulled the district's administrative order, allowing the mosque project to go forward. But when the construction resumed last August, local residents protested and spread false and offensive messages about Muslims.

Islamophobic messaging intensified

"Islamophobic pamphlets were distributed throughout the area, and rallies targeting our religion, Islam, were held," Muaz Razaq, a Ph.D. student from Pakistan who is the media representative for the KNU Muslim community, said in a news conference in April.

In a video Razaq shot last year, one placard near the building site said, in English, "Muslims who kill people brutally and behead them, get out of this area right now." Another said, in Korean, "Not all Muslims are terrorists, but all terrorists are Muslim."

Last October, a severed pig head appeared in front of the site for the first time. Razaq says he believes a neighbor of the site put it there. "That was a very disappointing moment for our whole community," he tells NPR.

A local residents' committee also hosted a pork barbecue party nearby.

Muslims are not allowed to eat pork under Islamic law. And people have used pork and severed pig heads as symbols of anti-Muslim hate in other parts of the world, including in the United States.

Kim Jeong-ae, the deputy chair of the residents' committee, argues the barbecue was a camaraderie-building gathering for residents in front of their houses, not an act of hate targeting the Muslim community or the mosque.

Kim says the issue is not what the building is, but where. "We are opposed to a public facility being built in the middle of a residential district with no public road. We would have objected to anything," she says.

Media reports say the residents are opposing Islam as a religion, but we don't really know about Islam. We are not interested.

Residents say they had put up with noise, cooking odors and crowding of the narrow street, and now fear that the inconveniences will only grow with the mosque.

"Media reports say the residents are opposing Islam as a religion, but we don't really know about Islam," says the resident Kim. "We are not interested."

Meanwhile, Muslim students and their family members who visit a temporary prayer hall right next to the construction site see the pig heads every time they come. Kim insists the display is done by an individual resident and has nothing to do with the committee.

Kim Ji-rim, a lawyer who represents the Muslim community here, says the South Korean legal system lacks a law against hate speech and is unable to judge that the pig heads are targeting Muslims or constitute a punishable offense.

When the students asked the police and the district office to remove the pig heads, the authorities responded there's nothing they could do under the current law, Kim says.

The district office of Buk-gu, Daegu, told NPR it cannot dispose of the pig heads, which it regards as private possessions placed on private property. The local police confirmed there is no law punishing hate speech or clear guidelines on how to handle acts like this.

The National Human Rights Commission of Korea, a government agency, said in March that putting pork in front of a mosque under construction to degrade Muslims does amount to hate speech and "should not be tolerated."

The commission can investigate rights violations against social minorities, but its intervention is limited to making recommendations to relevant authorities.

In the meantime, the lawyer Kim says, the students submitted a petition to the United Nations special rapporteurs on migrant rights and freedom of religion reporting the issues and are awaiting their confirmation that the residents' actions are discriminatory.

Since 2007, South Korea has made several attempts to legislate a comprehensive law that prohibits discrimination based on gender, sexual orientation, race, religion, disability, age and other factors. To the current parliament alone, four separate bills of this kind have been formally proposed.

All past attempts have been unsuccessful, due to fierce and organized opposition led by conservative Protestant churches. Christianity has the largest religious following in South Korea, with 20% identifying as Protestant in a 2022 survey by Hankook Research.

Razaq says conservative evangelical groups' involvement in this issue — holding rallies, issuing statements and participating in mediation meetings — has intensified tensions and hampered dialogue with residents.

KNU sociology professor Yi Sohoon, however, says South Korea can and must regulate hateful actions as a state party of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

But "there isn't anyone implementing it, so accountability and enforcement is an issue here," says Yi.

"The tolerance for hate under the existing legal framework is striking, and that is all the more reason for there to be a normative guideline to set a minimum standard and set the bar to tell people why certain actions are wrong," she says, calling for anti-discrimination legislation.

More foreign students come to South Korea

The Muslim community at KNU is one part of a fast-growing group of foreigners in South Korea — international students.

According to Justice Ministry data, the number of foreign national students enrolled in Korean colleges and universities surpassed 200,000 this year, compared to around 11,000 in 2001, when the government released a plan to recruit more international students.

Schools and the government are actively trying to attract more international students, to cope with the dwindling number of college-age Korean students. South Korea's total fertility rate fell to 0.78 last year, the lowest level among advanced economies.

Schools farther away from the capital, Seoul, are especially vulnerable to a shrinking pool of potential students. Several schools have already closed, dealing a blow to the local economy.

In Daegu, the country's fourth most populous city, KNU saw its number of international students jump from a single digit in 1999 to over 1,100 last year. After China and Vietnam, Muslim-majority countries like Pakistan, Uzbekistan and Bangladesh send the most students, according to the school's 2022 bulletin.

In the same period, the total number of foreigners staying in South Korea grew from 381,116 in 1999 to 2,245,912 last year, according to the Justice Ministry.

Sociologist Yi, who also heads a task force for peaceful resolution of the mosque issue, says international students like the Muslim students are "a valuable presence" for the South Korean government.

"The Muslim students here are actually closer to a group that South Korean government generally desires, you know, educated, high-quality migrants with education credentials that South Koreans understand," Yi says.

"But they come with something that South Korean society isn't used to, which is what they call — what they think is — a foreign religion."

In the country of just under 52 million people, the Korea Muslim Federation estimates that between 150,000 and 200,000 Muslims reside in South Korea, including 35,000 Korean Muslims.

The Justice Ministry, under the current government of President Yoon Suk Yeol, is pushing to overhaul the country's immigration policy and launch a new immigration agency, with the goal of increasing the working-age population.

The ministry has already increased the number of seasonal migrant workers and opened a new special visa track for regions with severely declined populations. It is also considering a plan to expand the quota for skilled workers who can stay in the country longer.

But the situation in Daegu shows that while South Korea considers immigration as a possible solution for its population crisis, the country is poorly prepared to live with migrants.

Migration policies for major migrant groups, such as marriage migrants and low-skilled laborers, have focused on assimilation and regulation.

In the absence of laws and policies addressing the country's growing multicultural reality, both the Muslim students and opposing residents complain of a lack of government intervention in their conflict.

Earlier this month, President Yoon attended a meeting of a special committee on immigrants and called for policies for their social status and rights.

"It appears that our society has avoided having real discussions on this issue," he said. "Despite the growing number of immigrants, our social perceptions have not changed."

NPR's Anthony Kuhn contributed to this story from Daegu, South Korea.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.