Lamont Davis starts off most mornings the same way at Bolton Elementary School in Cleveland: high fives, fist bumps and quick check-ins with students as they head in to get breakfast.

As Bolton’s family support specialist, a position that is financially supported by the Say Yes Cleveland program, it’s his job to notice things, big and small, to assess their needs. One student was late to school; another was misbehaving on the bus; another got a new pair of shoes.

“Our positions here are at least 80%, 90% relational,” Davis said. “That’s how we get to know the needs of our parents and our families and our children, is through having conversations and just making them feel like normal.”

The overwhelming majority of students going to Bolton Elementary, in Cleveland’s Fairfax neighborhood, are coming from low-income families, and the majority of them are Black. Davis says being present in these students’ and families’ lives means finding out what issues they’re facing at home – hunger, homelessness, and more – which serve as barriers to learning well in the classroom. Then, he can work with families to find local resources to work through those problems.

While Say Yes Cleveland – which started in 2019 - is mainly known as a “college promise” program, which pays for the college tuition of CMSD students who attend four years of high school and live in the district, the role of family support specialists in local schools goes far beyond preparation for higher education.

It’s part of the long game for Say Yes Cleveland, Cleveland Metropolitan School District, and the various local partners who support the program. CMSD CEO Eric Gordon reported earlier this school year that now every CMSD school and partnering charter school has a family support specialist present, a rapid expansion since 2019 when there were specialists at 16 schools, versus 104 now, a number that includes public charter schools that partner with the school district.

Jon Benedict, Say Yes Cleveland’s spokesperson, says the support specialist program came out of a recognition that giving students free college tuition isn’t necessarily enough to get them to college.

“Students, many of whom grow up in multigenerational poverty, face challenges and that their peers in other communities may not, and more importantly, often don't have the supports to overcome those challenges throughout their schooling and can be easily knocked off track academically,” Benedict explained.

But the results so far from having these specialists in schools? It’s hard to say from the data available, Benedict said. The pandemic and pandemic-related school closures caused an unprecedented interruption of education right in the middle of the expansion of the program. Some points do remain, however: the number of referrals family support specialists have made to connect families to services has jumped from 262 in 2019, to 1,497 in 2020, to 2,226 in 2021. Meanwhile, CMSD’s graduation rate jumped significantly in Say Yes Cleveland’s first year, but subsequently dropped once the pandemic hit.

Some of the work’s impact on academics can’t yet be measured directly, Benedict added. During the COVID-19-related lockdowns, family support specialists were delivering food and computers to families from the school district and other partners, for example. Their main goal is “prevention” of serious issues for students and their families like homelessness and hunger, an intervention that only pays dividends for things like students’ test scores and attendance over time.

“This is going to be looked at over years and decades really,” he said. “The idea is the impact we’re going to have is on a reduction in some real hardships [for students].”

But spending a day with the family support specialists makes it clear the critical role they’re playing.

A normal day at Bolton

Lamont Davis cuts a quiet but reassuring presence throughout the school day, stopping in classrooms to speak briefly with students who are on his radar, and getting updates from teachers’ on their well-being.

He meets Bella, a kindergartner, in the cafeteria as she picks up her strawberry Pop-Tarts. She’s arrived late today, and it’s her first day back at school. She shyly takes her food, trailing behind Davis, to meet her mother in the main office before getting ready to go to class.

Bella’s mom, Alieshia Braxton, has nine kids, five of whom go to Bolton. She’s not able to work because she’s spending so much time raising her kids, and so she’s gotten to know Davis well. When there are free coats being given out or local food distributions, for example, he lets her know.

“He's very helpful. He reaches out to me where he notices things that the children was lacking,” she said. “You know, as far as clothes, book bags, different resources he helps me out with.”

Vanita Hodges, better known as “granny” to some of the students, volunteers to help out at the school and has two grandchildren at the school. She’s a big fan of Davis too.

“He has much respect for the children; he’s awesome,” she said. “Without him at Bolton, I don’t know if this school would be like this because at first, before he got here, this school was outrageous.”

She said she’s noticed a marked improvement in students’ behavior since Davis arrived; fights are far less common.

Principal Charles Dorsey said part of that is because family support specialists like Davis are able to get to the root of students’ behavioral issues, because, often, those issues don’t start in the classroom. He said some students are being raised by their siblings, or their grandparents, and so it can be hard for them to get all the support they need at home.

“So I think it’s very important to have additional resources other than just the principal because we don’t have counselors, you know, so he acts as a counselor for our families,” Dorsey said.

This is a relatively calm day for Davis, but his students and their families regularly go through a lot, something that isn’t lost on him. He described one family who had come to Cleveland from another city, escaping a home where domestic violence occurred frequently.

“They moved here to Cleveland and they were in a shelter,” he said. “I know mom was probably very frustrated that day, and there was an incident with the child, and the department of Children and Family services came into the school and the child was removed from mom. That was probably one of the most heartbreaking incidents I’ve seen.”

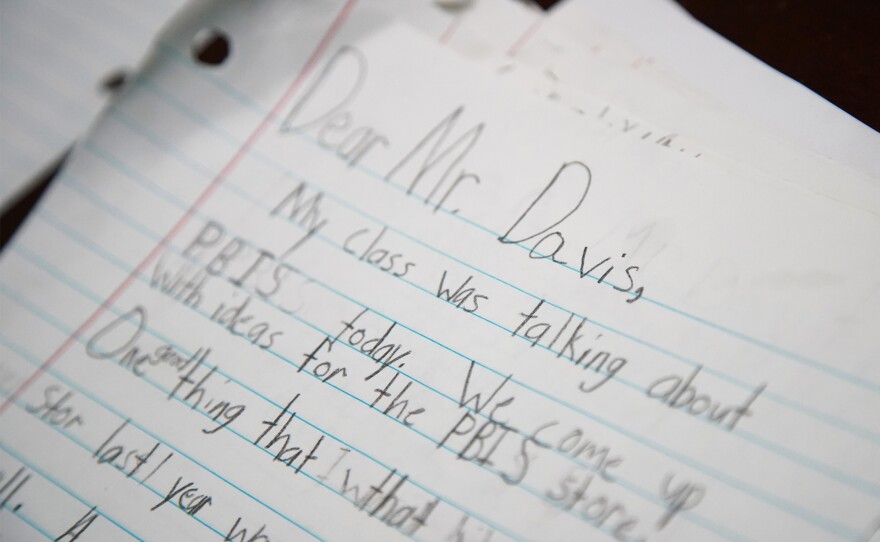

In many ways, these specialists are serving as necessary liaisons between children and their schools; Davis said many parents come to him first when they’re experiencing issues. And students do the same.

“So I’m their uncle, their aunt, their mom, dad, you know, anyone, even grandmother grandfather. You have to play those roles with the kids,” he said.

Family support specialists in Cleveland and abroad

Donna Dixon is a family support specialist at the Cleveland School of Science and Medicine on the John Hay High School campus in Cleveland.

Dixon says helping students address health and mental health needs occupies a big chunk of her time.

One girl had experienced “significant loss” during the pandemic, and her mother told Dixon she just didn’t seem like herself since. After a referral from Dixon to counseling, the mother told her she “got her daughter back.”

Dixon said trauma students experience needs to be addressed, and family support specialists are in a good position to notice when that intervention is needed

“Unfortunately, over the summer and at the end of the school year, we’ve had two students who’ve lost siblings due to gun violence,” she said. “We’ve had quite a bit of students experiencing significant loss… and we were able to provide them some supports and I was able to connect them over the summer to some grief counseling resources.”

Martha Kantner, CEO of College Promise, a national nonprofit advocating for college promise programs in schools throughout the country, says there are several hundred programs like Cleveland’s across the country. But many don’t have the kind of support CMSD is offering.

“The staffing in the schools is a feature that we want more promise programs to emulate,” she said. “Because early on we have too many students that don't have the aspirations to go beyond high school, whether it's a college or a career school.”

She said the support is “critical” because there’s a big “pipeline” problem; the leaks in the pipeline are poor student literacy scores and math scores in elementary and middle school, which leads to poor performance down the road, meaning college isn’t even an option for students, even if it’s provided to them for free.

In New York, Say Yes Buffalo is a college promise program that got started before Cleveland’s. Its family support specialist program has been running since 2011, and in many ways is providing similar supports that Cleveland’s program does.

Sylvia Lane, director of preventative services at Say Yes Buffalo, said they’ve traced a lot of improvements in students’ schooling to the presence of family support specialists. Chronic absenteeism has decreased and attendance has improved for students whose families are helped by the specialists. At the same time, their academics improve. Plus, their parents become more aware of services available to help them in the community.

“We try to think of ourselves as removing the non-academic barriers to help a student be successful academically,” she said.

So what’s the future hold?

Promise programs are expensive to run. There’s a huge amount of money needed to support free college tuition for students for an extended period of time. Additional support services are expensive, too.

Say Yes Cleveland has raised $96 million of about $125 million needed to pay for students’ tuition over the next 20-plus years. But the funding for the Say Yes support specialists comes on a year-to-year basis, being appropriated by leadership with Cuyahoga County and CMSD. Jon Benedict, Say Yes’ spokesperson, said the cost to run the support specialist program this school year alone is $9.6 million.

With leadership changes coming for both the county government and the school district, it’ll be up to the future administrations to continue support for the programming.

Sylvia Lane, with the Say Yes Buffalo program, said her organization realized it needed to specialize its services in order to meet needs funders and the community were looking to address. They were essentially worried about the same thing that could happen in Cleveland – changes in leadership affecting funding for support services.

Bearing that in mind, the family support specialists are now split into two groups. One, funded by Erie County’s Child Protective Services, deals with the “preventative” side of things, she said, helping students and their families address homelessness, hunger and other issues that often coincide with poverty.

The other group of family support specialists, funded by Medicaid, works specifically with students who have at least two serious medical or behavioral health issues. A child with asthma and ADHD, for example.

In that way, Say Yes Buffalo has created more stable funding to support each initiative, and foster closer relationships with the other parts of the social services system that many parents are already networking with, Lane said.

“Nobody’s perfect, but we’ve gotten really, really good at managing our relationships between schools, the county and families,” she said.

CMSD CEO Eric Gordon said in his State of the Schools speech that it’ll be a difficult proposition for anybody to take the programming away, though.

“If the next CEO comes in and says, 'I don't like that 'Say Yes' stuff, I'm going to get rid of these wraparound supports," Gordon said. "Those same people that raised $95 million are going to come sit in that person's office and say, you are about to turn off scholarships for kids for the next 21 years. Do you want to rethink this?"