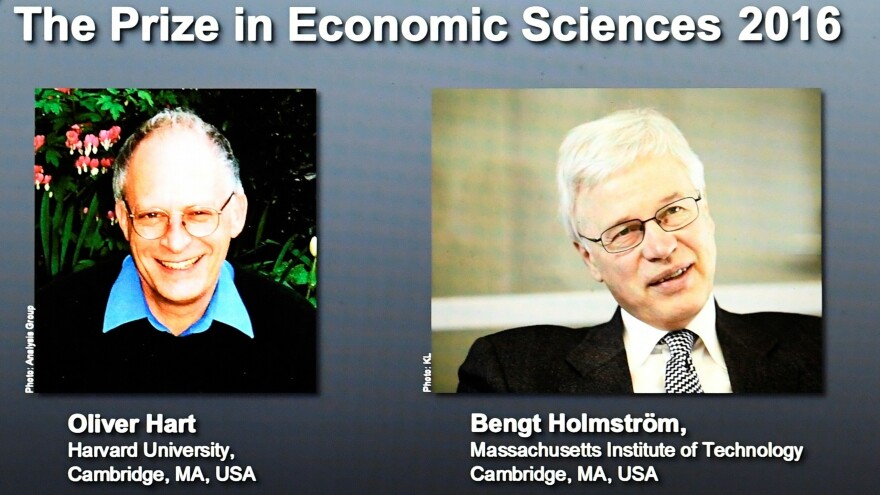

The 2016 Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded Monday to Oliver Hart and Bengt Holmström for their work in contract theory — developing a framework to understand agreements like insurance contracts, employer-employee relationships and property rights.

The issues they have worked on are ripped from the headlines — should prisons be privatized? — as well as deeply familiar to anyone who's earned a paycheck or paid for insurance.

Holmström's work has explored how to balance risk and incentives — both in idealized theory and in real-life situations. One early insight, according to the Nobel committee, was that high-risk industries should have more fixed salaries while stable industries should more often consider performance bonuses.

The questions Holmström and his co-authors considered are concrete ones: How do you reward CEOs for improving a company's performance, without just showering them with money when the company is thriving because of luck? How do you evaluate teachers' performance without encouraging them to teach to a test? How does incentive pay need to change as an employee's career progresses and they are less likely to be motivated by future promotions? How can a team be rewarded for effort without incentivizing free-loaders to slack off and profit off their colleagues' work?

Hart, meanwhile, explored a fundamental shortcoming of contracts — namely, that no one can predict the future and there are too many future variables to possibly codify all of them in a contract.

So, when the unforeseen inevitably pops up, who decides how to deal with it? This is the field of "incomplete contracts," and Hart wrote that a contract should identify who has the right to make future decisions — a significant kind of power.

The theory of incomplete contracts provides a way of thinking about which government services can benefit from being privatized, and which are better off under government control. Here's the background summary provided by the Nobel committee:

"Suppose a manager who runs a welfare-service facility can make two types of investment: some improve quality, while others reduce cost at the expense of quality. Additionally, suppose that such investments are difficult to specify in a contract. If the government owns the facility and employs a manager to run it, the manager will have little incentive to provide either type of investment, since the government cannot credibly promise to reward these efforts. If a private contractor provides the service, incentives for investing in both quality and cost reduction are stronger."

Hart found that privatized services have a strong incentive for cost reduction — but often at the expense of the quality of services provided. Hart accordingly raised concerns about private prisons.

The work of the two laureates has influenced not just economics but law and politics, the committee writes in a press release.

Hart was born in England and Holmström in Finland, but both have made their careers in the U.S.; Hart is a professor at Harvard and Holmström is a professor at MIT.

The Economics prize was established nearly 50 years ago and was not one of the original Nobel Prizes. Its full name is the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.

The prizes in physiology or medicine, physics and chemistry, as well as the Nobel Peace Prize, were announced last week. The prize in literature will be announced on Thursday.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxMzY2MjQ0MDEyMzcyMDQ5MzBhZWU5NA001))