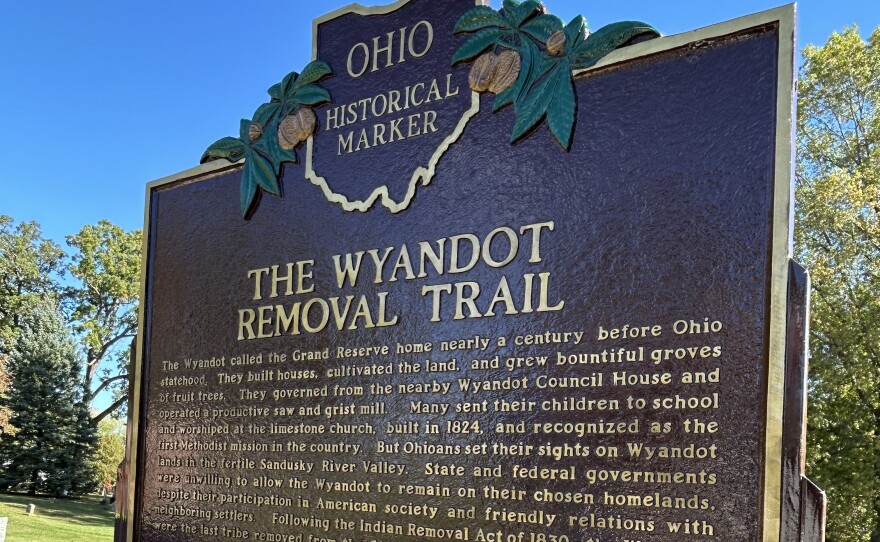

The first in a new series of historical markers being unveiled this weekend tells the story of the last Indigenous nation removed from Ohio. Thirteen markers will be installed over seven years along the Wyandot Removal Trail from Upper Sandusky to Cincinnati.

There are no federally recognized tribes headquartered in Ohio today. They were forcibly removed in the 1700s and 1800s.

The Wyandot were the last. Forced from their homelands in Upper Sandusky in 1843, more than 600 people walked over 150 miles south to Cincinnati, where they boarded steamboats bound for Kansas City. They numbered just around 200 by the time they were displaced a final time to Oklahoma.

"A lot of people don't realize that the reason we left Ohio was not because we wanted to leave. We were forced to leave."Kim Garcia, Wyandotte Citizen

An existing historical marker in Sandusky describes the forced removal as a "departure" and a "journey." That didn't sit well with Rebecca Wingo, an associate professor of history in the University of Cincinnati's College of Arts and Sciences and director of the public history program.

"The marker there was installed in 1999. That marker is problematic. 'Departure' seems like a voluntary word. It also talks about their 'journey' to Cincinnati, and you're like, 'Oh, well, it was a removal trail,' " she explains. "When I read that marker, I thought to myself, 'Wow, we could really do better, and we could probably do more.' So I contacted the cultural division of Wyandotte Nation, introduced myself and said, 'Would you be interested?' And they took a leap of faith, thankfully."

She and some of her students began working with the Wyandotte Nation, headquartered in Oklahoma, to correct that history, and tell the broader story.

In their own words

There currently are around 7,356 enrolled citizens of the Wyandotte Nation.

"I think a lot of people of Ohio don't realize or recognize that the Natives that called Ohio home are still living, still thriving," says Kim Garcia, a Wyandotte Citizen and the nation's cultural preservation officer. "Also, a lot of people don't realize that the reason we left Ohio was not because we wanted to leave. We were forced to leave. That's what this project is about; to say we wanted to stay in our homelands of Ohio, but we had to be removed."

Garcia worked with Wingo's team, along with Heather Miller, another Wyandotte Citizen and the nation's Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) coordinator, and other tribal citizens to finally control their own narrative. They have the final say over what language is used on the signage.

"There's so many places where misinformation is being represented, and oftentimes the way that we tell our own history is not being told in those places," says Miller. "By giving us the ability to control that narrative, to tell our own story, to tell our own history, we're reclaiming that and being able to provide a different perspective for folks to learn from and to understand a bigger picture of the story of Ohio."

Miller adds, "We are strong, independent, and incredible survivors. I think that is really important. But then we also have this intimate knowledge of the land, certain aspects of the area that's really unique to us, and so we bring this unique perspective to these places that although we're not physically here, we still have that knowledge, we still have that understanding, and we have that relationship with this land that we want to bring back and we want to share with folks. Because the more that we can do to understand this place, the better we can all take care of the land and take care of each other."

Historical markers

The first marker will be dedicated Saturday beside the Wyandot Mission Church, the oldest Methodist mission in the country, according to Congressional record. Founded in 1816, the building was constructed in 1824. Wingo's team worked with the church's modern day stewards, the congregation of the John Stewart Methodist Church. The mission church and three acres of land upon which it sits, along with a portion of a the accompanying cemetery were deeded back to the Wyandotte Nation in 2019.

The new marker serves as the beginning of the Wyandot Removal Trail. Wingo explains that it sets the scene for the removal.

"They left on July 11, 1843, and they gathered there the day before. One of their leaders — he was actually a reverend in the church, Reverend Squire Grey Eyes — he delivered a farewell address there. They bid farewell to their homes, but also (to) their buried loved ones, and the futures that they thought they would be able to realize within the state," says Wingo.

"By giving us the ability to control that narrative, to tell our own story, to tell our own history, we're reclaiming that and being able to provide a different perspective for folks to learn from and to understand a bigger picture of the story of Ohio."Heather Miller, Wyandotte Citizen

They packed all of the worldly possessions they could carry, leaving behind the summer crops that they should have been storing to sustain them through the winter months, and began the arduous trek southward.

Two additional markers will be unveiled in May in Cincinnati and Lebanon.

The Cincinnati marker, in North Bend's soon-to-open William Henry Harrison Riverfront Park will detail the tribe's complicated relationship with the United States' 9th president, William Henry Harrison. Wingo says he was both friend and foe throughout his lifetime.

The marker in Lebanon is one of the more difficult ones, Wingo says. It describes how the Wyandot were treated in towns across Ohio as they made their way south.

"Everywhere they go, they are being harassed and poked and prodded and watched. The newspaper accounts talk about the Wyandots as a 'melancholy spectacle' or an 'imposing procession.' I struggle to imagine not only the trauma of leaving one's homelands, but then having everyone come out and just watch. It is just a very weird thing to imagine. The marker in Lebanon really tries to convey the voyeurism involved in their removal," she says.

Editor's Note: The two spellings of Wyandot and Wyandotte are purposeful. "Wyandotte" is used in reference to the modern-day nation headquartered in Oklahoma. "Wyandot" is inclusive of all the bands of Wyandot people dispersed across modern-day Canada and the USA. After prolonged contact with the British, the traditional name "Waⁿdát" (Wandat) was corrupted into "Wyandot" sometime in the 1730s-1750s.

Read more: