It's not often that a writer can illustrate his own books, but Brian Selznick is that rare find. He began his career as an artist collaborating with authors on children's books. But he gradually realized that he wanted to tell his own stories in both words and pictures — and to do that, Selznick invented a unique narrative device.

Wonderstruck is both a novel and a picture book, a form Selznick first experimented with in The Invention of Hugo Cabret, when he had the idea of telling a story in much the same way that film does.

"I thought: Is there a way of combining what the cinema can do with panning, and zooming in and out, and edits, and what a picture book can do with page turns, and what a novel does?" Selznick says.

Selznick's illustrations work like a camera, zooming in on details and following his characters around as they move through the world. In the beginning of The Invention of Hugo Cabret, the reader follows a boy through a grate in the wall, down a hallway, to an old man in a toy booth who sees a clock, and behind the number 5 in the clock, there's the boy ... (Click here to see that opening sequence of drawings.)

In Wonderstruck, Selznick wanted to take this narrative experiment a step further. "I had this idea to try to tell two different stories," he says. "What if I told one story just with pictures, and then told a completely different story that was set 50 years later with words? And then had these two separate stories weave back and forth until they came together at the end?"

Wonderstruck is the story of Rose and Ben, a young boy and girl who live years and worlds apart. By the end of the book, the reader learns they have a special connection. But from early on, they have one thing in common: She is deaf, and he loses his hearing when he is struck by lightning.

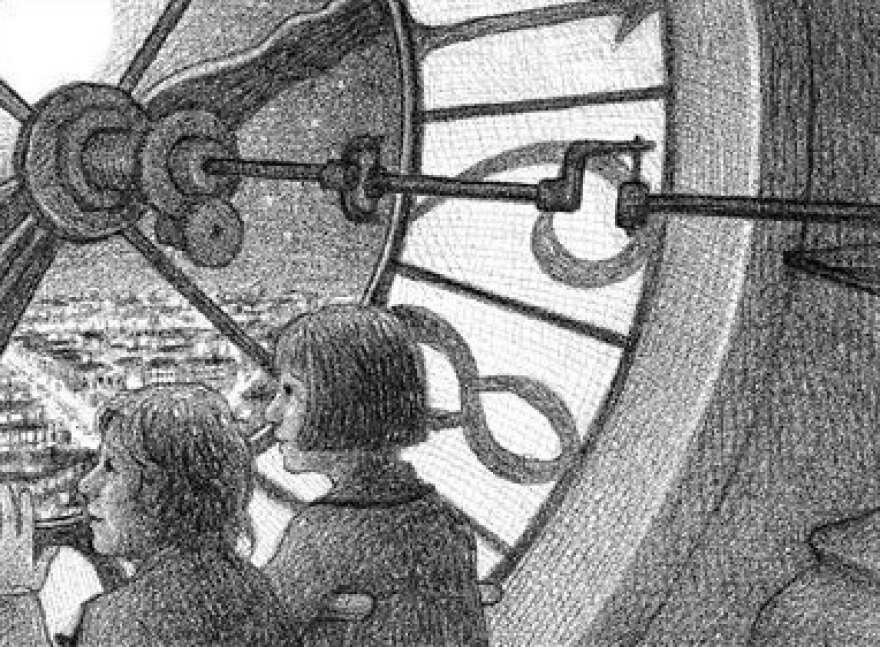

Selznick says the idea for the book began forming when he saw a documentary about deafness and deaf culture. One of the deaf educators emphasized how hyper-attuned deaf people are to the visual world. So Selznick set out to tell the story of a deaf character in pictures. "We experience [Rose's] story in a way that perhaps might echo the way she experiences her own life," he explains.

Rose's story, told almost entirely through Selznick's compelling black-and-white illustrations, alternates with Ben's story, which unfolds in written form. At first, the reader is not sure how the two stories relate, but here and there, the characters' worlds collide. Both get caught in a storm, both go in search of their parents, both find refuge in New York's Museum of Natural History (one of Selznick's favorite destinations when he was a kid growing up in New Jersey). When Ben and Rose finally do meet, Selznick says, the book becomes all about how we communicate with each other.

"At the end of the story, we have scenes where there's a deaf character who signs, a hearing character who signs, and a deaf character who doesn't sign — and they all have to have a conversation," Selznick says. "And so who speaks, who writes, who can sign ... it all becomes mixed up until they can figure out a way to communicate."

Creating these books is a complicated process, Selznick says, and he is always a little surprised in the end when everything comes together. When he's in the middle of it, it's a little like looking for buried treasure.

"It's sort of like going through a treasure map backwards in a certain way, where I know what I want it to be, but I don't know how to get there," he says. "It does end up feeling like I have been on this really exciting journey that I ultimately hope that the reader will be excited to be on, too."

A writer and artist who is fascinated with film, Selznick is about to see a fantasy come true: In November, the film version of The Invention of Hugo Cabret, directed by Martin Scorcese, will be released on the big screen.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

![<strong>A Wordless World: </strong>The story of Rose, a deaf little girl in Brian Selznick's <em>Wonderstruck</em>, is told primarily in pictures. "We experience [Rose's] story in a way that perhaps might echo the way she experiences her own life," Selznick explains.](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/79f5628/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1000x620+0+0/resize/880x546!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.npr.org%2Fassets%2Fimg%2F2011%2F09%2F12%2Fwonderstruck-62-63_custom-a3788e795c398cc5b6436d9129206bf044f651f2.jpg)