CUDA: This scientific blockbuster is based on a just completed analysis of the skeletal remains found 15 years ago in Ethiopia. It’s taken this long for researchers to be sure of what they had found. Yohannes Haile-Selassie is the curator and head of physical anthropology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Then a graduate student at the University of California Berkeley, he's the man who found the first piece of evidence - a human finger bone.

HAILE-SELASSIE: We definitely knew that it was an early human ancestor remain. The first piece was sort of half of a finger bone and then later, looking around we found the other half. Eventually we decided we had more than just finger bones...

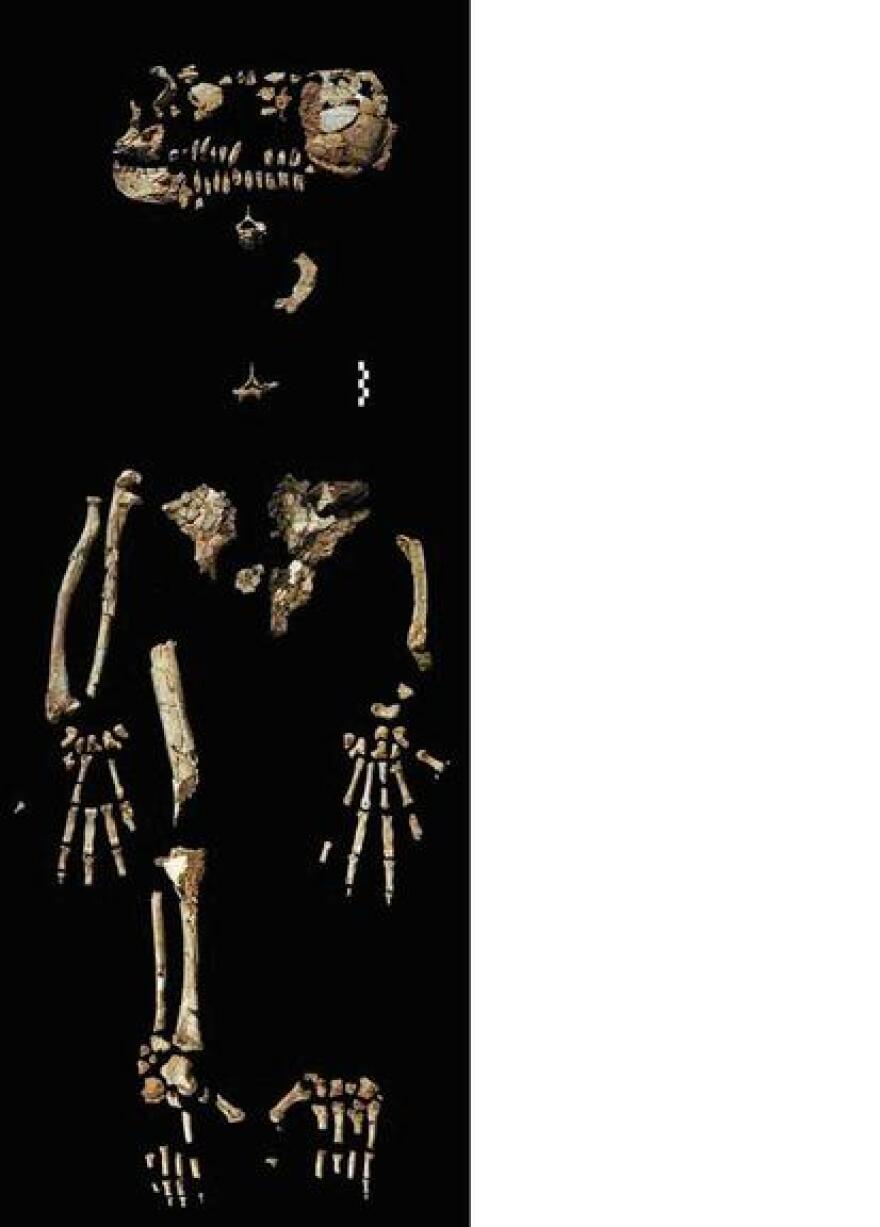

CUDA: That was the start of what would turn into three years of painstakingly tedious excavation – and result in the fairly complete skeleton of one of the oldest humans ever discovered…They call her Ardipithecus ramidus – or “Ardi” for short. She was about 4 feet tall, weighed roughly 100 pounds and lived 4.4 million years ago. That makes her more than a million years older than Lucy—the famous ancient human skeleton found in the same region two decades earlier. After years of analysis and vetting by many other scientists the team came to the conclusion that they were looking at something never seen before. Bruce Latimer is an associate professor of anatomy and anthropology at Case Western Reserve University and the former director of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

LATIMER: We found a human ancestor that climbs trees --it has a grasping foot. But when it comes down to the ground it walks on two legs. So we really found that transitional animal that I would not have imagined.

CUDA: The transitional animal he is talking about is what scientists imagine ancient humans might have looked like as they evolved from a common ancestor to modern apes --who climb trees and walk on their knuckles --and modern humans who walk upright on two legs. Ardi’s hands, spine and wrists are much more like those of modern humans than modern apes but her feet, particularly her big toes are much more ape-like.

Apes have a specialized big toe that sticks out and allows them to grip objects like a thumb. This gripping action is what gives them the ability to climb. The tradeoff is that the position of that opposable big toe prevents them from having an arch in their foot – and that makes walking upright on two feet for long distances impossible. But over time, the bones of the modern human foot moved – the toes lined up straight – and the foot developed a shape that was better designed for walking. Ardi however – has a foot that does both – giving scientists a picture for the first time, of what our human ancestors might have looked like as they evolved from tree climbers to land dwellers. Scott Simpson, assistant professor of anatomy at Case Western Reserve School of Medicine explains.

SIMPSON: What the Ardipithecus skeleton shows is that we never ever went through a chimpanzee-like anatomical phase. And what we find is, in many ways, the Ardipithecus skeleton is more like modern humans than it is like chimpanzees. And so we had to come to grips with the fact that we were looking at an animal that no one had ever seen before and was functioning in ways unlike modern humans and unlike apes.

CUDA: And so what will the new science textbooks say about human evolution?

SIMPSON: They won’t simply be able to modify the existing chapters- they're going to have to add a new chapter because this is that different from everything else.

CUDA: And that new chapter may read something like this: New fossil evidence indicates humans did not evolve from apes – but rather from a shared ancestor with some human and some ape-like features. Gretchen Cuda, 90.3