Until 2007, when it was unearthed by a Columbia University undergraduate, few scholars were aware of the record of fugitive slaves written by Sydney Howard Gay. Gay was a key Underground Railroad operative from the mid-1840s until the eve of the Civil War. He was also the editor of the weekly newspaper the National Anti-Slavery Standard.

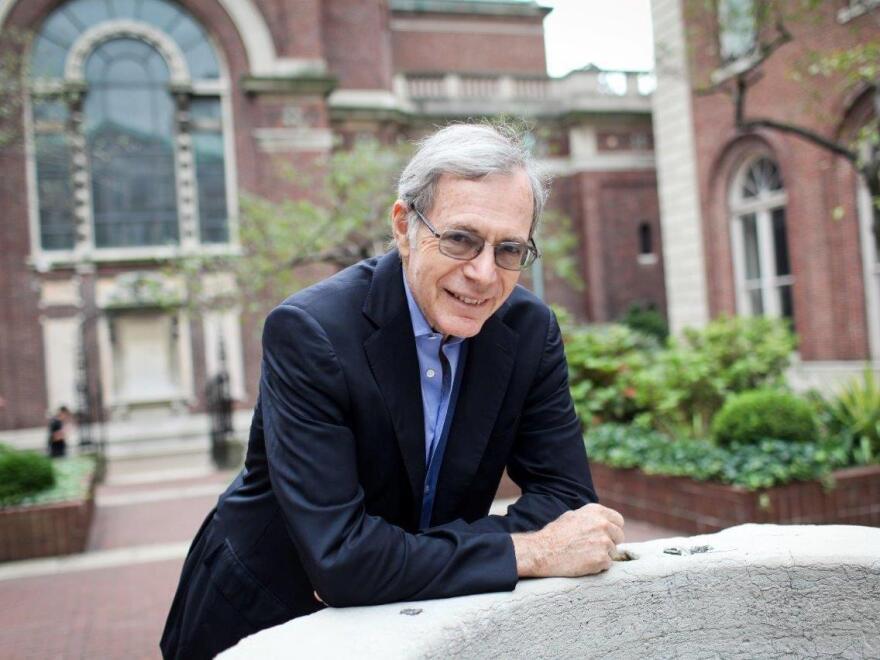

When historian and Columbia University professor Eric Foner saw the document, he knew it was special: It listed the identities of escaped slaves, where they came from, who their owners were, how they escaped and who helped them on their way to the North.

"A lot of information we have of the Underground Railroad is really memoirs from a long time after the Civil War and you know ... people's memory is sometimes a little faulty, sometimes a little exaggerated," Foner tells Fresh Air's Terry Gross. "So here we have documents right from the moment these things are happening — and it's a very unusual and revealing picture of the world of these fugitive slaves and the people who assisted them."

Foner's new book, Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad, focuses on New York. According to Foner, the city was a crucial way station in the railroad's Northeast corridor, which brought fugitive slaves from the upper South through Philadelphia and on to upstate New York, New England and Canada.

"This was a great social movement of the mid-19th century — and these are the things that inspire me in American history," Foner says, "The struggle of people to make this a better country. To me, that's what genuine patriotism is."

Interview Highlights

On the different methods of transportation slaves used to escape

We tend to think of fugitive slaves ... individually running away, hiding in the woods during the day and traveling at night. But Gay's records indicate that certainly by the 1850s, when the transportation system was well-matured, many of these fugitives escaped in groups, not just alone. ... And they escaped using every mode of transportation you can imagine. They stole carriages — horse-drawn carriages — from their owners, they went out on boats into [the] Chesapeake Bay, little canoes, and tried to go north. Large numbers of them came either on boat from Maryland or Virginia, places like that — they stowed away on boats, which were heading north, often assisted by black crew members — ... or by train. The railroad network was pretty complete by this point and quite a few of these fugitives managed to escape by train, which is a lot quicker than going through the woods. ...

The records that [Gay] kept give a real sense of the ingenuity of many of these fugitives in figuring out many different ways to get away from the South.

On fugitives leaving family behind

Everybody left somebody behind, whether it was a child, parents, brothers, sisters, cousins, et cetera. ... Occasionally you did have family groups managing to escape together, but obviously escaping with a young child would be a rather difficult thing — it would make it much more likely you'd be captured. So this record and other documents of the time are full of rather heartbreaking stories of people who got out and then had to figure out, "Well is there any way I can get some of my relatives [out]." That was not very easy most of the time. ...

Most of the slaves who escape and who are mentioned in this record are young men — men in their 20s, basically. ... Maybe a quarter were women. ... This is part of the human tragedy of slavery that even the act of escaping put people in an almost insoluble kind of dilemma.

On the typical dangers on the way to freedom

The whole South was kind of an armed camp. There were obviously police forces around, there were slave patrols. These were people whose job was to watch out on the roads for slaves who were off their farms or plantations for any reason. ...

Then there was the general status of slaves, you might say. Under the law ... every white person was supposed to keep their eyes open for slaves who were violating the law in some way. You could be stopped by any white person and be asked to show your papers. If a slave was on the road in some way they had to have "free papers" to prove they were a free person or some kind of pass from their owner giving them permission to go to a town or to visit another plantation or something like that.

The Underground Railroad was interracial. It's actually something to bear in mind today when racial tensions can be rather strong: This was an example of black and white people working together in a common cause to promote the cause of liberty.

Frederick Douglass — who escaped from Maryland before the Underground Railroad was really operative in a strong way in 1838 — ... he wrote in his autobiography about the fear that he felt [that] every white person might be after him. ...

There were professional slave catchers, some of whom went to the North. I give stories of people who were seized in Philadelphia or New York City, sometimes without any legal process at all, and just grabbed and taken to the South, back to slavery.

On how the Underground Railroad was organized

We think of [the Underground Railroad] as a highly organized operation with set routes and stations where people would just go from one to the other, maybe secret passwords. It wasn't nearly as organized as that. I would say it's better described as a series of local networks ... in what I call the "metropolitan corridor of the East," from places like Norfolk, Va., up to Washington, Baltimore, in places in Delaware, Philadelphia, New York and further north. There were local groups, local individuals, who helped fugitive slaves. They were in communication with each other. Their efforts rose and fell. Sometimes these operations were very efficient; sometimes they almost went out of existence. The Philadelphia one basically lapsed for about seven or eight years until coming back into existence in the 1850s.

So one should not think of it as a highly organized system. ... What amazed me is how [a] few people can accomplish a great deal. In New York City, I don't think more than a dozen people at any one time were actively engaged in assisting fugitive slaves, but nonetheless, they did it very effectively. ... I developed a great deal of respect for what a small number of people can do in very difficult circumstances. After all, they are violating federal law and state law by helping fugitive slaves.

On the myth that white abolitionists were the heroes

The No. 1 myth, which I don't think is widely held today but certainly had a long history, is that the Underground Railroad, or indeed the entire abolitionist movement, was [the] activity of humanitarian whites on behalf of helpless blacks — that the heroes were the white abolitionists who assisted these fugitive slaves. Now, they were heroic — and I admire people like that who really put themselves on the line to do this — but the fact is that black people were deeply involved in every aspect of the escape of slaves. ...

In the South, [escapees] were helped by mostly black people, slave and free. When they got to Philadelphia or New York City, local free blacks assisted them all the way up. ...

The Underground Railroad was interracial. It's actually something to bear in mind today when racial tensions can be rather strong: This was an example of black and white people working together in a common cause to promote the cause of liberty.

Copyright 2023 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.