Joy Harjo, the nation's first Native American poet laureate, has a very clear sense of what she wants to accomplish with her writing.

"If my work does nothing else, when I get to the end of my life, I want Native peoples to be seen as human beings," she says.

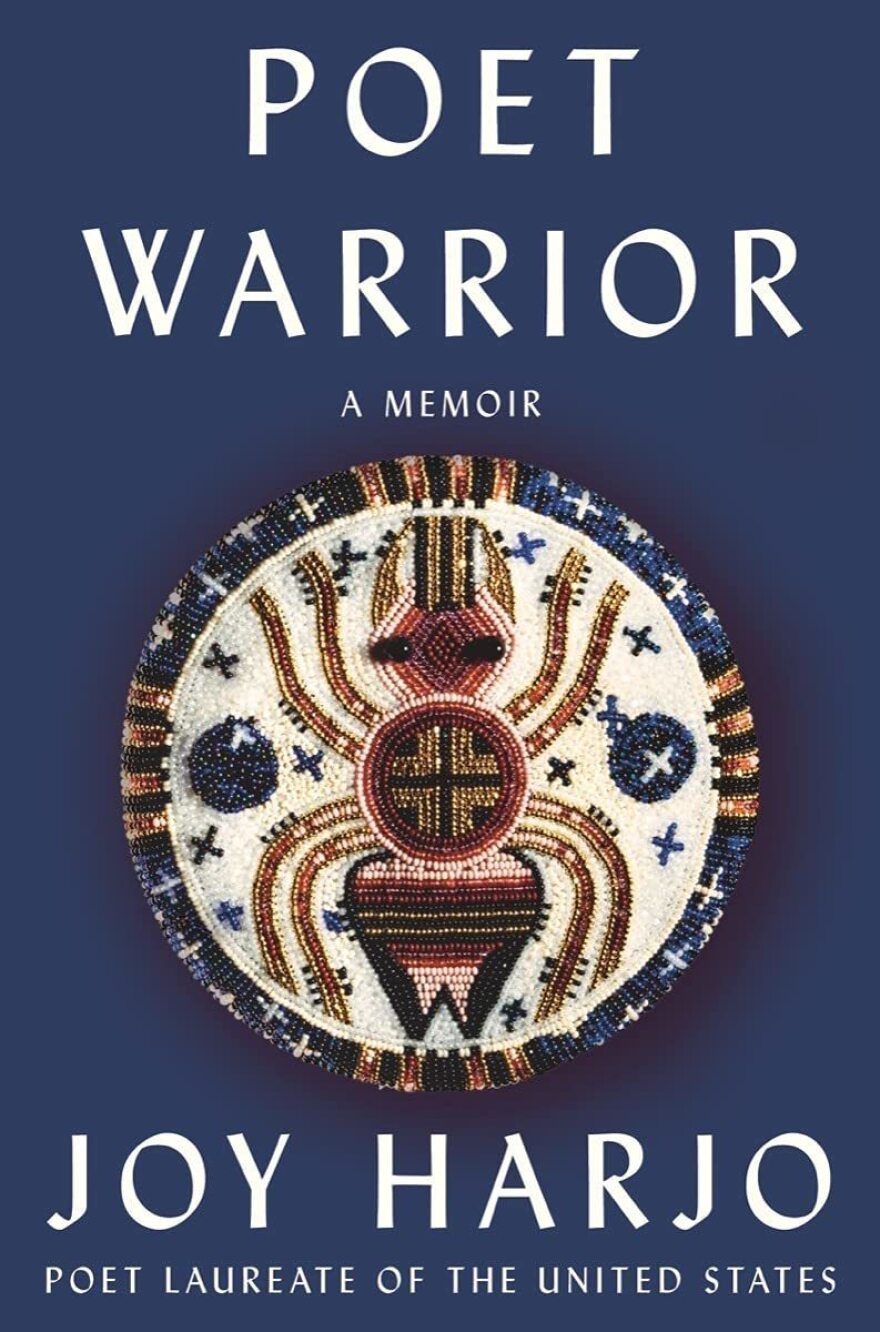

Harjo, who lives in Tulsa, Okla., is a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. Her new memoir, Poet Warrior, tells the story of her sixth-generation grandfather who survived the Trail of Tears, the 19th-century forced march in which the U.S. government moved Native people from their ancestral homeland in the Southeast to territory that later became Oklahoma.

Harjo's memoir is also a personal story about how she learned to find herself in the spiritual world. She's had several dreams that have marked major turning points in her life — including one in which she carries her seventh-generation granddaughter into the world.

"It was one of those dreams that I know that it happened, it is happening or it will happen," Harjo says. "The world that we live in is not just the 3-D physical world, but we live in a world that's so multi-dimensional and it's so deep and it's so mysterious. ... There's always something to learn."

Interview highlights

On respect being key to her beliefs and center to her work

I've come to realize that what has motivated my art-making is really a strong need for justice, for "people" to be treated [with respect.] And then when I say people, I also mean animals and insects and the birds and the earth and the earth person that we are all part of — that there's a key element and that's respect. And my work has always been motivated by that need for respect.

On how her ancestors were forced off of their lands in the Trail of Tears

President Andrew Jackson went against Congress to remove Southeastern Native peoples from the lands there into Indian territory, or what became known as Oklahoma. Of course, we did not go willingly. There were several scuffles and fights and even massacres against this illegal removal. But we were force-marched from our homelands.

I think a lot of America thinks it was only the Cherokee — or the so-called "five civilized tribes," that included the Muscogee (Creek) — but these kind of removals or forced migration or marches happened all over the country. We were moved because a lot of people wanted those lands. They were very rich, the Southeast [lands], were very rich in resources and water and animals and plants and so on. But we lost probably at least half of our peoples on that march due to hardship, freezing, violence, rape, all kinds of things that happened on those different removal marches.

I think a lot of America, when they think back in history and see Natives, we were hiding out in the woods, wearing rags and so on, but we had huge societies. I have a great, great, great uncle who had the largest horse-racing establishment on the Eastern Seaboard, a Muscogee (Creek) man and half Irish. And they wanted that, they wanted what we had.

On the Native empowerment movement of the '60s

In the late '60s, I was at Indian boarding school in Santa Fe, New Mexico, not your usual boarding school, but it was an arts school, and I remember hearing about Martin Luther King being killed and all of that was on the news. And we were all young Native artists there, from eighth grade to two years postgraduate, and we were working on art and we'd stay up late nights talking and making art together and talking about what it meant to be a Native person and about history and about how our art was part of history making.

On her early activism

I remember sitting as a young person, as a student, sitting in on meetings with coal companies, uranium companies in the Southwest, with Native peoples attempting to get a voice in or attempting to turn the story towards respect for the Earth, the respect for the people, to take care of the quality of water, the quality of people's lives. And I remember at one point going out to do a story, just after the [1979] Church Rock uranium spill, and there were children out playing in the water and in the livestock and the Navajo speakers were saying, "We need a word." How do we come up with a word that will tell the people that even though you can't see it, there is something dangerous here that can harm you and you can't use these waters, when it was the only source of water for their livestock?

On loving books as a child

The only book we had in our house, I think, was the Bible. And I liked the pictures, often there were pictures in those books, or at least the one we had. And when I went to first grade, when we started to learn how to read, I was so thrilled about what happened with symbols and that suddenly it opened up a world to me. I read all of the books in the first grade classroom and was sent into the second grade, and it became like a hunger for me. I liked the sounds, of course, I like the sound that words make. I like the percussion, the percussive elements and the images and so on. Just like the same kind of thing I heard in my mother's song-making. But the more I read and the more the ability grew, the deeper I could read, the more stories and I could be transported in — much the same way that I could be in that kind of visionary dream world when I was younger. And when we get to about 7 — and I think this happens to a lot of us — we forsake those realms of knowing and understanding, and reading helped give that back.

On her belief that babies are born with help from their ancestors

I don't believe that we come into this world alone. We have assistance from, I guess, what people call the "other side." There's interaction that goes on. I've learned this, especially being an artist of a writer, a musician, that there's resonances. ... I have always felt ... my great grandfather, Henry Marcy Harjo, around me exactly when I needed him or his wisdom. And I think it's true for everyone.

I have been at the births of several of my grandchildren, and someone always walks them in, so that when I was writing this memoir and I had a dream towards the end of writing it, and in the dream, I was carrying my seventh generation granddaughter into the world. It's a ritual we all do, you know, where you open the blanket and you look at them and you admire them and you look at who's coming in and you welcome them. And sometimes you can see their gifts and what they're bringing in and you give them a blessing.

Lauren Krenzel and Thea Chaloner produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz , Molly Seavy-Nesper and Meghan Sullivan adapted it for the web.

Copyright 2022 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.