Find out more about our Reverse Course series here.

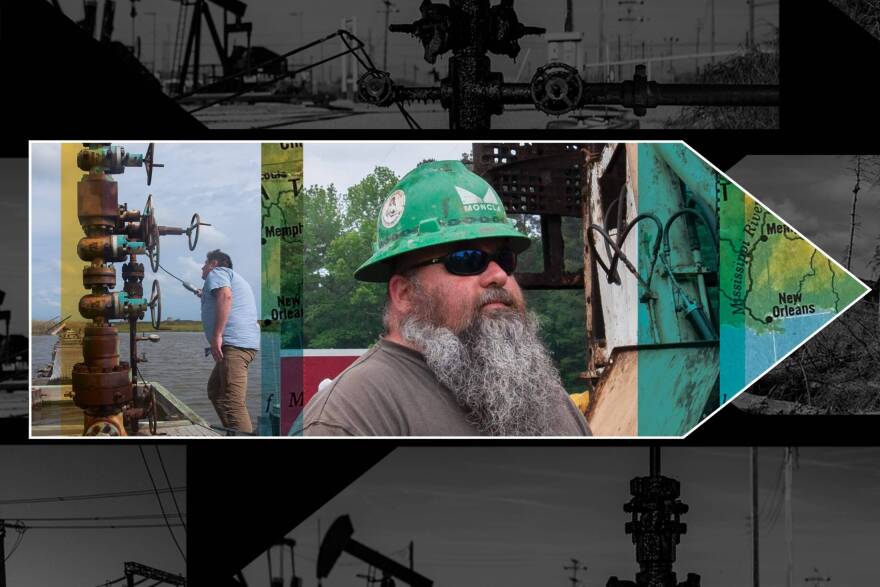

As an oil worker and well site supervisor, Druis Trahan has seen a lot of abandoned wells. But each one is a little different.

Today’s job started simple enough. Unlike with some abandoned wells in the wilderness, this one was easy to haul equipment to — it’s just off a road that runs by some ranches in Greenwood, Louisiana, outside Shreveport. But Trahan says they can’t yank out the tubing, the steel pipe that runs down 3,900 feet into the earth, which means the job just got more complicated.

Well number 202188 was drilled in 1985, but hasn’t produced any oil or gas since 2010. It’s been sitting in the middle of this pasture in Greenwood, Louisiana ever since.

Workers cap an “orphaned” well in Greenwood, Louisiana that hasn’t produced any oil or gas in more than a decade. (Chris Bentley/Here & Now)

There are hundreds of thousands of “orphan” wells like this one across the United States, named for the fact that they have no legal owner responsible for them. President Biden’s infrastructure bill created a $4.7 billion program to fix that, but the federal money is not enough to plug every well.

When oil and gas wells reach the end of their useful lives, fossil fuel companies are supposed to plug them before moving on. But that doesn’t always happen. And even when it does, wells can leak harmful gasses, including climate-warming methane.

The company that owned well 202188 stopped responding to regulators and eventually had its business license revoked in 2018. At that point, the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources put all of the company’s wells on the state’s orphan list and banned the company’s owners from drilling again in the state.

There are currently more than 4,500 wells officially listed as orphans in Louisiana, and some 15,000 inactive wells pose similar risks. It’s a similar story in many other states. The Environmental Defense Fund estimates 14 million Americans live within a mile of a documented orphan well.

Patrick Courreges of the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources says it’s become an increasingly common fate for drillers to land on the state’s orphan list.

“A couple of different things have happened. One, you’ve had a couple of real nasty downturns in the oil patch when you see oil prices drop,” he says. “This isn’t generally your ExxonMobils or your Shells. These are small operators who may operate dozens of very low-performing wells. And when you see that price drop, they get no margin. They don’t have investors. They can’t keep them up or they just go out of business. We end up having to orphan them.”

That means the state ends up paying to clean up and maintain those old wells, often tens of thousands of dollars per site. Some of that money comes from fees drillers pay to pump oil and gas in the state. And Louisiana is among several states tightening rules on companies to make it harder for them to walk away without properly plugging their wells. There are also plans to leverage carbon credits for more funding.

A map of orphan wells in the U.S. (Courtesy of the Environmental Defense Fund)

But even the most stringent regulations aren’t enough to cover the mounting costs of cleaning up after what might be as many as 2 million abandoned and inactive wells nationwide.

That’s where the money from the infrastructure bill comes in. Courreges says it’s doubling, maybe tripling, the number of wells they’re able to plug this year.

“None of this fixes the problem. It just helps,” he says. “Every well we get plugged, that’s one less place you’ve got access from oil and concentrated brine and methane to get to the surface.”

Active wells actually leak a lot more than abandoned ones, says Amy Townsend-Small of the University of Cincinnati, who has been studying methane emissions from the oil and gas industry. There are about 1 million active wells and roughly 3 million inactive wells in the U.S.s

“We need to clean those up,” she says.

Townsend-Small’s research also shows it’s a relatively small percentage of leaky wells that are responsible for most of the emissions. But it’s hard to know the full scope of the climate impact because she says some leaky wells could be flying under the radar.

“That’s true for abandoned wells as well as active wells,” Townsend-Small says. “Because there’s so many abandoned wells, we don’t know if we’ve accurately measured or captured how many of these very high-emitting abandoned wells are.”

Leaky wells in the Gulf

It’s easy to find leaky wells in the shallow waters off the rapidly disappearing coast of southern Louisiana.

Flocks of hungry seabirds chase shrimp boats while pelicans and bottlenose dolphins weave through oyster beds marked with long bamboo poles. All those animals contend with another fixture of the Gulf ecosystem: 10-foot tall stacks of criss-crossed rusty pipes and valves, euphemistically referred to in the oil industry as “Christmas trees.”

Bamboo poles mark oyster beds near an abandoned platform once used for oil and gas production in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana. (Chris Bentley/Here & Now)

These are old oil and gas wells that are either “shut-in,” meaning they’re sealed temporarily and might go back into production someday, or abandoned and left to decay in the Gulf.

Well number 157032 landed on Louisiana’s orphan list almost 30 years ago. The state’s report from 2017 — the last time it was inspected — notes the “cribbing is rotten” and it appears to have only deteriorated more in the years since.

Scott Eustis, community science director for the environmental group Healthy Gulf, leans out of his boat and swipes a methane detector over the rusty pipes. It beeps immediately.

When Justin Solet reaches out to touch one of the valves, it accidentally lets out a puff of gas.

“This is supposed to be closed,” says Solet, a commercial fisherman and former oil worker who now works with Healthy Gulf. He’s also a member of the United Houma Nation, a state-recognized indigenous community. There’s a slightly raised patch of land with a tree on it visible from Well 157032; Solet says that’s an ancestral mound, sitting right next to a rotting well.

“We’ve seen that it’s leaking,” he says. “There’s about an inch of the original casing that has completely rusted off. If this was hit by a barge or accidentally hit by a boat, it would fall over. If it were hit by a hurricane, another one like Ida, I don’t know if it would withstand it.”

There’s still wreckage from Hurricane Ida visible along the coast. Not far from another orphan well off Port Sulphur, steel storage tanks lie crumpled in the water, thrown off their platforms when Hurricane Ida made landfall in 2021.

There are thousands of wells that dot the bayous along the shores of southern Louisiana. Many are still in operation, and many shut-in or inactive wells have been properly plugged. But others are leaking, and some can be smelled almost as soon as they can be seen. Richie Blink, captain of Delta Discovery Tours, says “the air tastes like you’re downstairs at a Jiffy Lube.”

‘We’re just not keeping pace’

Scott Eustis of Healthy Gulf says the state should be paying more attention to this area when deciding where to spend that federal money for plugging wells.

“The Department [of Natural Resources] can plug around 300 orphan wells a year, but the list grows sometimes by 1,000 a year. So we’re just not keeping pace. And they’re not being prioritized by methane. They’re being prioritized by how cheap it is per well,” he says. “We’re arguing that if you get in the water, if you get on the coast, if you get in the places affected by hurricanes, you’re going to be abating more methane.”

Reducing methane emissions is one of the main reasons the federal government is devoting billions of dollars to finding and plugging old wells. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas.

In Louisiana, if state inspectors find a methane leak on a well, they note it in reports that are supposed to inform which wells get plugged first. But it’s not the only thing regulators there consider, and some wells are left to spew methane for years even after a leak has been reported.

An abandoned well in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana leaks dark fluid. (Chris Bentley/Here & Now)

“The Department of Natural Resources has a wonderful prioritization process, but they absolutely do not follow it,” says David Levy. He runs a company that makes parts for the oil and gas industry and used to serve on Louisiana’s Oilfield Site Restoration Commission. He quit in part because he says the state wasn’t doing enough to address methane emissions.

Now he tracks emissions on his own by flying around southern Louisiana in a small plane — a Magnaghi SkyArrow — with methane sensors on the wings.

He says it’s easy to find massive leaks that are going unaddressed, not just from orphan wells, but from improperly shut-in wells and active fields, too.

“I can fly over almost any field and find methane,” Levy says, “so there are magnitudes larger numbers of wells that are just ignored that are leaking just as much methane as orphan wells are.”

And recent research suggests that federal regulators are also underestimating emissions from large oil rigs farther offshore.

Levy wants to see the federal government take over from states like Louisiana and start plugging the leakiest wells and oil fields themselves.

For its part, the state says it’s developing a plan with Louisiana State University to better address methane leaks, using all the data it’s gathering from the recent uptick in well-capping work.

“Regulators in the U.S. are geared for looking for big leaks, big releases, historically, not so much looking at the cumulative impact of a lot of little leaks,” says Patrick Courreges, with the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources. “That’s changing. But part of change is figuring out, okay, how do we do it differently? How do we do it better?”

‘They need to give back’

That change is happening too slowly for environmental groups like Healthy Gulf and members of the United Houma Nation, a tribe in southern Louisiana that is not federally recognized. That means they can’t access federal funds for cleaning up orphan wells on tribal lands.

Clarice Friloux says she and her neighbors in Grand Bois, Louisiana, regularly come across remnants of the oil and gas industry.

“It’s been part of our lives,” says Friloux, who took Exxon to court over oil field waste in the 1990s. “In the early ‘30s and ‘40s, oil and gas came through the Houma Nation properties. And of course, our people were not allowed to read and write in those years. So our land was taken away from us by a signature of a promise of a lease. So all my life, I’ve seen the pipelines. The same pipelines are still there.”

An abandoned well about a mile and a half off the coast of Buras, Louisiana, sheltered by eroding wetlands. Native American mounds are visible on the left. (Chris Bentley/Here & Now)

Friloux would like to see oil companies pay more to clean up for the damage their industry has caused to Louisiana’s coast and to Native people.

“They need to give back,” she says. “You can’t just take and take and not return.”

Justin Solet, the former oil worker who now works with Healthy Gulf, is also a member of the Houma Nation.

“With that sovereignty comes the ability to sit at the table and negotiate that our ceremonial and our religious places should be protected,” he says, “and not invaded by dead iron and leaking oil wells and gas wells.”

The Louisiana Oil and Gas Association declined requests for an interview, and requests to other industry groups were not returned.

But the biggest emitters might have to start paying more soon. In addition to states including Louisiana tightening their own regulations on orphan wells, the Inflation Reduction Act put a new tax on methane emissions starting next year. The Environmental Protection Agency is still writing rules for how to administer it.

Healthy Gulf’s Scott Eustis says one thing the government and industry can do right now is start listening to the people who live on the coast.

“There’s a budget to plug these wells because of the methane problem, but we’re not measuring the methane,” he says. “We’re going to do better if we bring those federal moneys into the coastal waters and we’re going to do better if we recognize the United Houma Nation because maintaining our coastal culture is part of how we’re going to survive.”

That coastal culture could include underemployed oil workers, too, says Leo Lindner of the group True Transition. Lindner was a mud engineer in oilfields for years until the Deepwater Horizon disaster in 2010. Now he advocates for other workers like him.

“We’re looking to move them either into the green industry or into remediating orphan wells,” Lindner says. “We need a federal agency, well-funded, to create projects, to repair all this damage, the wreckage of industry. We can create union jobs. And with the oil field hiring less and less people, they’d be perfectly fitted for a lot of that work.”

This article was originally published on WBUR.org.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.