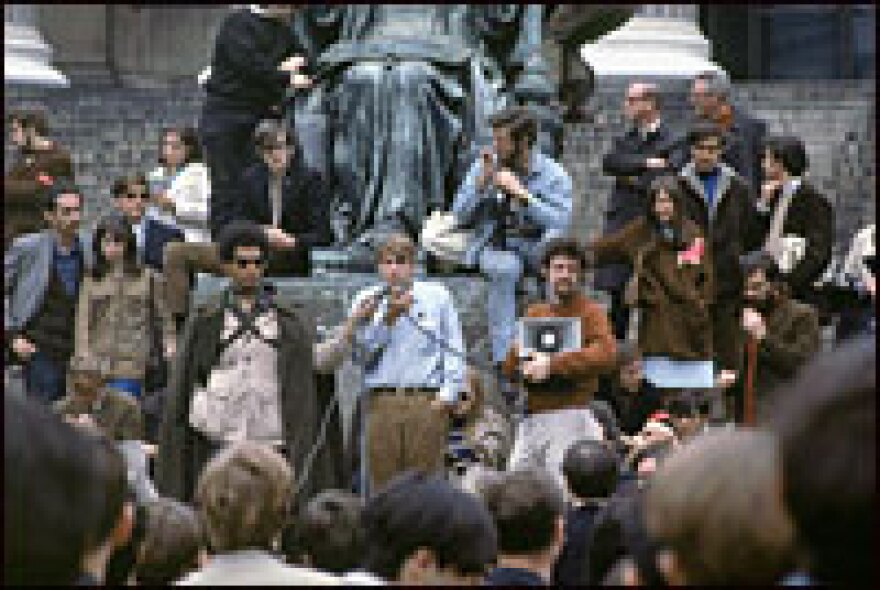

Forty years ago, Columbia University was a frequent scene of demonstrations against the Vietnam War and the university's relationship with its surrounding New York neighborhoods. Now, scholars and many involved in those protests disagree about their impact.

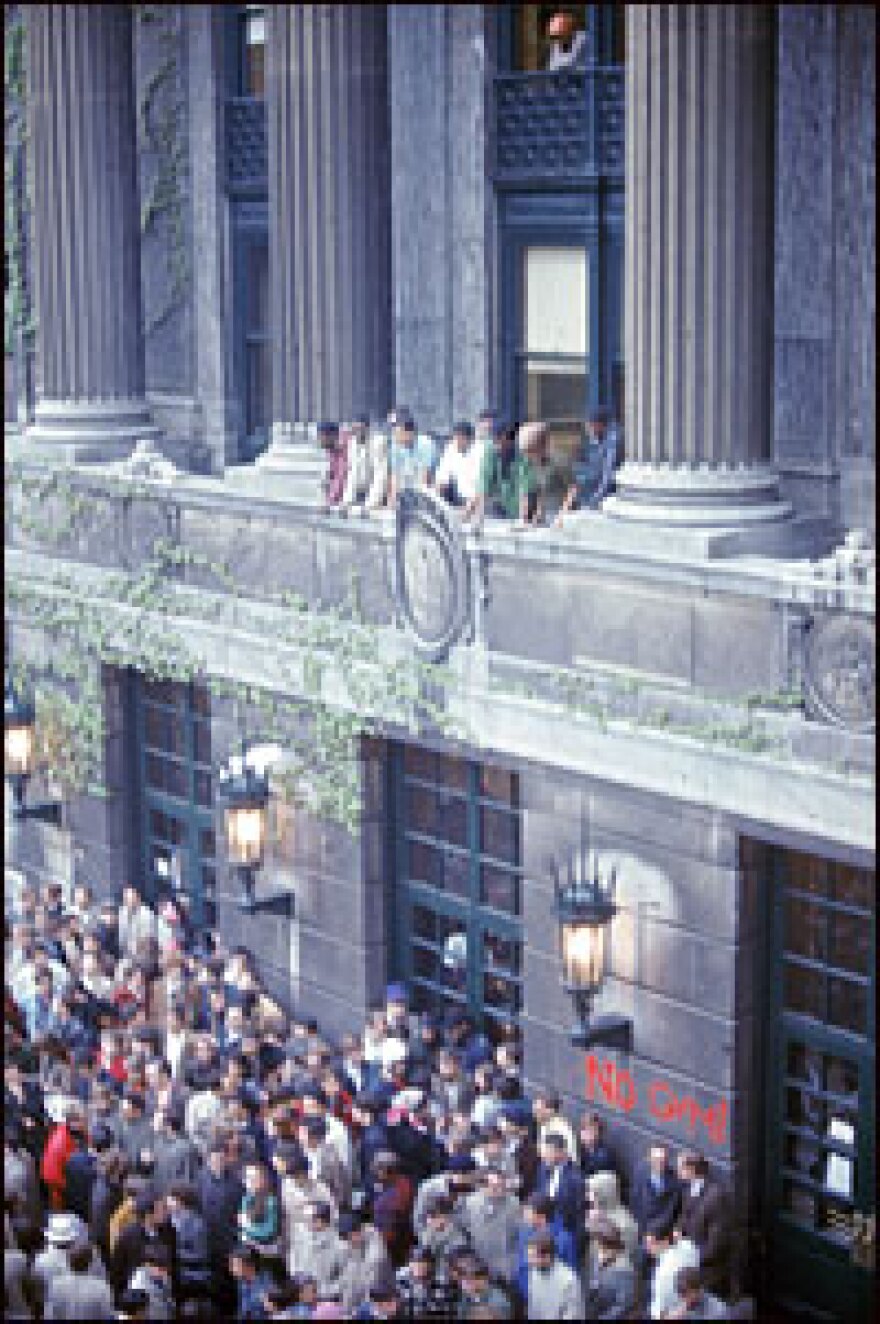

One source of contention was a university gym under construction in nearby Morningside Park. Black Harlem community activists, along with both black and white Columbia students, opposed it because they believed neighborhood residents would get only limited access to the facility being built on public land. On April 23, 1968, about 150 students and community members marched to the construction site and tore down a section of fencing. Then they moved on to Hamilton Hall, taking over the building and taking as hostage Columbia's acting dean, Henry Coleman.

Meanwhile, another issue drew some students' ire. Members of the radical group Students for a Democratic Society opposed Columbia's ties to a think tank involved in weapons research for the Vietnam War.

A Combustible Combination

Mark Rudd, then-chairman of Columbia's SDS chapter, tied the two issues together, saying at the time that students would not attend a university that exploited black people and developed weapons to kill them and murder the Vietnamese.

Within days, five buildings were occupied. Some students held counterprotests, calling for university life to return to normal. There were attempts to negotiate and mediate; the administration agreed to suspend work on the gym but refused amnesty for student protesters. On April 30, police moved in and cleared the buildings, arresting 712 students. More than 100 students, four faculty members and a dozen police were injured in the fracas. Students called a strike, and the campus shut down for the rest of the semester.

Today, Rudd is a retired math teacher who remains proud of his role in the protest movement.

"I see it as part of the enormous part of the anti-Vietnam War movement involving millions of people," says Rudd, who lived underground as a revolutionary for seven years. "We stopped a war of aggression."

Different Takes on History

But Rudd's perception of the movement's impact is not shared by Allen Silver, a sociology professor who has taught at Columbia since 1964.

"The army of North Vietnam stopped the war, because it imposed costs on the American polity and society that it was not prepared to bear," says Silver, who believes Rudd is deluding himself.

Silver contends the student radicals' view — that the university was part of an evil, imperialist system and deserved to be overthrown — was deeply destructive.

Silver contends the student radicals' view — that the university was part of an evil, imperialist system and deserved to be overthrown — was deeply destructive. He says various protests "played into the hands of the Nixonian repression" and helped the arguments of conservatives who followed — from Ronald Reagan to George W. Bush.

"The liberal universities were among the last refuges of real freedom — disciplined freedom, intellectual freedom, cultural freedom — from plastic America and Nixonian America," Silver says.

Many former Columbia activists of the time take issue with Silver's account.

Robert Friedman, a journalist who now covers world finance, says the Columbia strike was "a success." He doesn't believe that radical students' extreme militancy fueled a backlash that helped Republican candidate Richard M. Nixon beat Hubert H. Humphrey in the fall's presidential election.

Louise Yelin, who is married to Friedman, teaches literature at the State University of New York at Purchase. She believes the Columbia protests fueled continuing movements for change: civil rights, the environment and most important to her, feminism.

Yelin saw 1968 as a year of momentous change, "a spur to a new way of looking at the world and also to a feminist movement that changed our lives in many ways," she says.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.